Brexit is not a simple story of disruption. Policy-makers in the throes of Brexit should not forget another driver of structural economic transformation: the so-called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. Analysing the two drivers of labour market disruption together demonstrates the unique challenge of reconciling future planning with handling immediate shocks. Current uncertainties must not prevent strategic scenario planning and longer-term economic re-orientation, write Christopher Pissarides, Anna Thomas (IFOW), and Josh De Lyon (LSE).

Brexit is not a simple story of disruption. Policy-makers in the throes of Brexit should not forget another driver of structural economic transformation: the so-called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. Analysing the two drivers of labour market disruption together demonstrates the unique challenge of reconciling future planning with handling immediate shocks. Current uncertainties must not prevent strategic scenario planning and longer-term economic re-orientation, write Christopher Pissarides, Anna Thomas (IFOW), and Josh De Lyon (LSE).

The UK economy is experiencing two major forces of disruption. The first, Brexit, will involve a sharp change in the structure of economic activity. Membership of the European Union has shaped the British model of capitalism and the structure, and operation, of core industrial sectors. Factors listed in the World Bank ‘Ease of Business’ index, including those that influence trade across borders, are a stark reminder that the UK’s high current rating is linked to near-frictionless trade and investment flows with the European Union. Whichever form Brexit takes, this is set to change.

The impact of technological disruption, the second great force behind change in the British economy, is less immediate but nevertheless drives a different sort of structural transformation. In the longer run, technological innovation ought to be our main driver of growth. The positive and negative effects of technological disruption are not, however, evenly distributed across sectors and regions. Evidence of this unequal distribution can be seen in the recent experiences of communities formerly dependent on traditional manufacturing, who have suffered the impacts of deindustrialisation since the 1980’s. Research suggests that voting and turnout patterns in the Brexit referendum may well have been linked to this: the relationship between our two forces runs deep.

This article discusses how differentials are likely to be exacerbated by the onset of Brexit. As the ‘double disruption’ works together, the challenges will be deeper than those faced by other European countries that have only technological disruption to deal with. Further, they will be experienced at an individual, community and national level, inviting a period of policy activism by Government targeted at our most vulnerable regions. This will need to address the dampening of technological progress, as well as the growth of in-work poverty, and will demand critical shock management combined with a range of longer-term policies aimed not only at generating good local jobs in new and growing sectors, but also at supporting worker transition.

Brexit

It is now common knowledge that a No Deal Brexit is likely to cause living standards to fall sharply, with a probable reduction in UK income per capita by around 8%. The economic effect of other forms of Brexit are less certain, but the Government’s analysis predicts that GDP would be 1.6% lower if the UK remains in the Single Market compared with 7.7% lower in the WTO scenario over a 15-year period. This will impact individuals mostly through lower wages but is likely to affect other aspects of ‘good work’ too. These are identified in the Institute for the Future of Work’s Charter for Good Work and include: access to work, terms and conditions of employment, conditions of work, work quality, and choice.

The short-term adjustment process will be profoundly disruptive, especially in the case of a No Deal Brexit. Transitions tend to involve job change or displacement across sectors and regions as resources are reallocated and the economy adjusts to its new structure. Inevitably, this has implications for the skills that employers demand, as well as productivity and salaries. It is concerning that wages and job-related education and training have already been cut in sectors most likely to be exposed by Brexit and therefore are most in need of these policies [Centre for Economic Performance, research not yet published]. Other Brexit-related trends already biting include a rise in prices due to devaluation of the pound, which has caused real wages to shrink; and businesses cutting back on EU exports due to increased uncertainty.

The UK labour market will be affected in two main ways. First, downward pressure on labour demand is anticipated due to rising trade barriers and a fall in the inflow of foreign investment. Evidence to date suggests this will hit some industries dramatically: manufacturing, retail and transport stand out. These adverse effects will be most severe in the event of a No Deal Brexit. The consequences of other scenarios are less clear but foreign investment and trade flows will almost certainly decrease in the immediate aftermath.

Second, British migration policy is set for an overhaul. The Government has proposed a “skills-based immigration system” based on an independent report by the Migration Advisory Committee. The thrust of the proposal is to encourage high skill workers to immigrate to the UK and restrict immigration of low skill workers. An example can be seen in the new ‘tech talent’ visa scheme. In theory, this approach could put upward pressure on the wages of resident lower income workers. However, as we explore below, potential benefits are likely to be offset by a significant overall contraction.

Technology

Meanwhile, technological innovation continues to affect the UK economy at an increasing pace as costs diminish and rapid adoption continues. This should be good: technological progress increases aggregate productivity and is the main driver of long-term economic growth, as our Industrial Strategy recognises. Under appropriate conditions, technological innovation ought to translate into higher pay, increased average living standards and a reduction in poverty. But change and gains from technological progress are not spread evenly, meaning that technological disruption has important implications for both regional and wage inequality: technology grows the economic pie but alters the way in which the pie is cut. Managing a smooth transition for displaced workers, re-distributing resources into growing, more productive industries and redistributing new wealth and benefits are key. Focus on building a sustainable future of good work across the UK is central the success of these objectives.

The economic outcomes of workers displaced by technology are a good indicator of current trends and trajectories. Workers in shrinking occupations tend to experience a significant hit to their earnings relative to comparators in constant or growing occupations. The need for investment in human capital to facilitate training, reskilling and other support so that displaced workers can adapt to new lines of work is already increasingly pronounced. If and when Brexit kicks in, this need will become acute.

Brexit and technology

The exact manifestation of these shocks, and their interaction, is impossible to predict. We can, however, identify and map the UK sectors and regions already which are fielding the adverse effects of technological disruption, and are set to be hardest bit by Brexit (and therefore most likely to suffer the ‘double disruption’ we have identified). Brexit and technology, acting together, will increase the speed and process of disruption to the UK labour market. Divisions will be exacerbated, whilst the positives of technological change will be muted in the immediate aftermath. Growing in-work poverty experienced in front-line sectors is set to increase further. Those feeling the pain most sharply may be further exposed by employment law provisions that may not survive Brexit: protection for collective redundancy, working time, and agency work.

Restriction on immigration may well cause a tighter labour market, increasing the cost of labour and encouraging the adoption of technology. Bank of England intelligence has already observed that tight labour markets have encouraged the adoption of new technologies in some sectors, even though the UK has lagged behind its neighbours over the last decade. Were this increase in adoption a stand-alone trend, it would be very welcome.

Falling inward investment linked to Brexit will, however, dampen this positive emerging trend. The resultant economic contraction is likely to result in a fall in labour demand. This will stretch the labour market, making it less tight, exerting downward pressure on wages, and reducing incentives to adopt new production technologies. Inward transfer of technology may also fall because technology is known to move with firms. Increasing trade barriers and the greater administrative cost of trade may erode profitability and reduce the potential market size for British businesses. The absence of trade agreements is likely to add barriers to the exchange ideas, information and to conducting internationally collaborative work beneficial to technological innovation on a global playing field. Together, this will the hamper adoption and innovation use of technology, and the UK’s ability to respond to disruption with agility will be impaired. The UK’s ranking on the new ‘Global Labour Resilience Index’ (Whiteshield Partners in collaboration with the Institute for the Future of Work, Oxford, HSBC and ManPower Group) will fall.

In short, recent progress the UK has made with regard to technological innovation, and leadership in AI-related technologies in particular, is likely to reverse.

The two major outcomes of this reversal are very significant for the future of work in the UK, and the national economy after Brexit: firstly, technological growth will be muted, and secondly, existing regional inequalities will worsen.

Sectoral analysis

We have analysed the ‘double disruption’ in 3 major UK sectors and identified regional spread.

Manufacturing

Traditional manufacturing employment has been declining for nearly four decades, with many struggling regions never recovering. Technology has repeatedly altered the way in which production has taken place, and facilitated the fragmentation of the production process, so that labour-intensive tasks can be moved off-shore. Although the quality of remaining jobs may have improved with the reduction of more routine tasks, it is no coincidence that many Leave-voters reside in the areas most affected by deindustrialisation.

The story of British manufacturing does not end there though. The manufacturing industry is heavily dependent on international supply chains across the globe, especially for the production of more complex goods. If tariffs are introduced for border-crossing then the cost of importing and exporting final and intermediate goods will increase. In the short run, this will mean higher costs to firms, and reduced foreign demand for exports, both of which will put more jobs at risk. In the medium and longer term, there are abundant signs that manufacturing firms may decide to locate production plants outside the UK to reduce the frictional costs of trading. For example, Nissan has just chosen Japan as its location to build the next X-trail car and Airbus (which employs 14,000 people in the UK) has threatened that it could leave the UK in the case of No Deal, and a recent survey suggested that nearly a third of businesses are considering moving operations overseas due to Brexit. Pay and quality of work in remaining jobs will be at risk, likely leading to a higher level of in-work poverty. More research is needed on in-work poverty trends by sector, but pay and work quality are known to be key indicators.

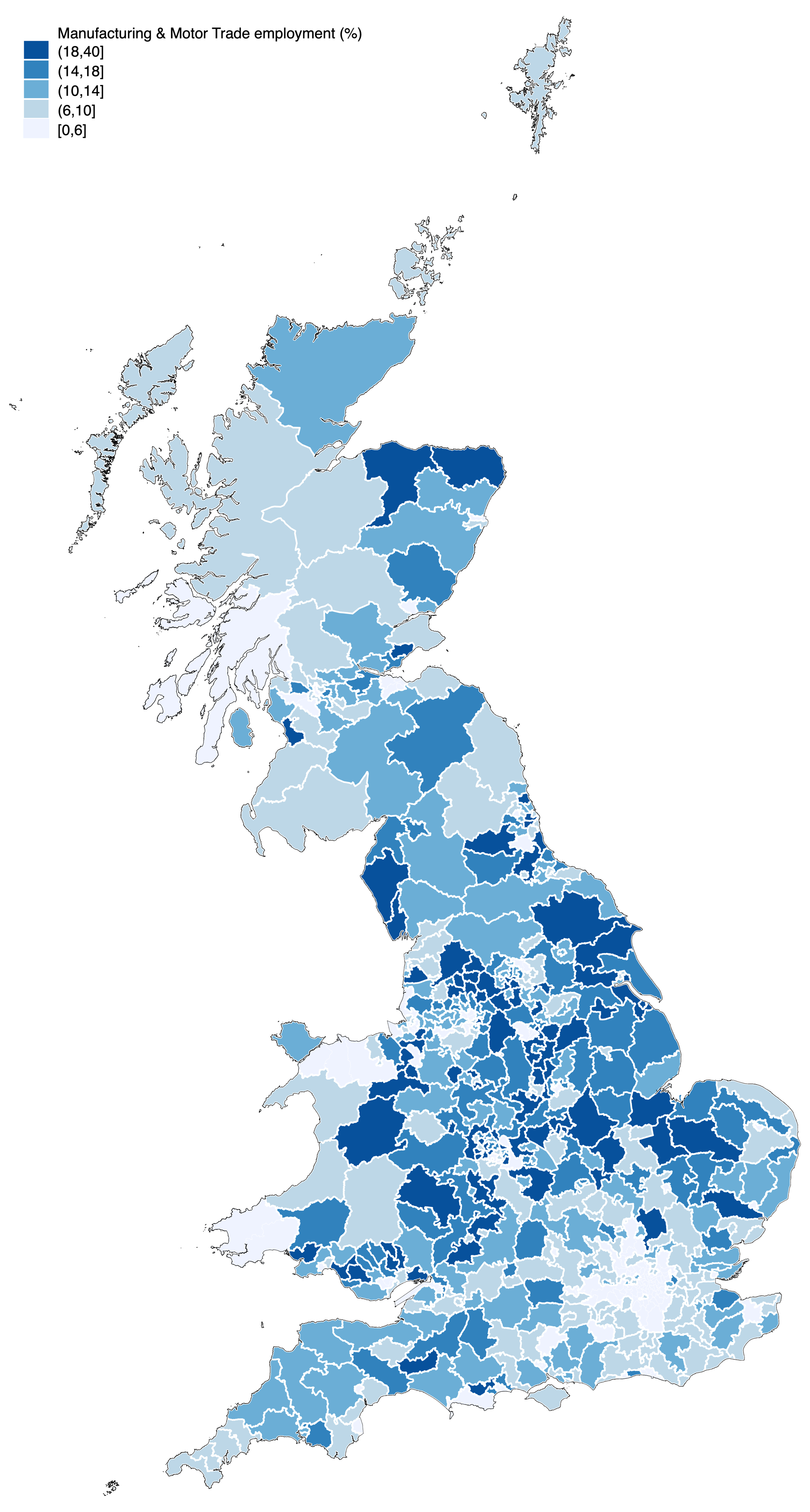

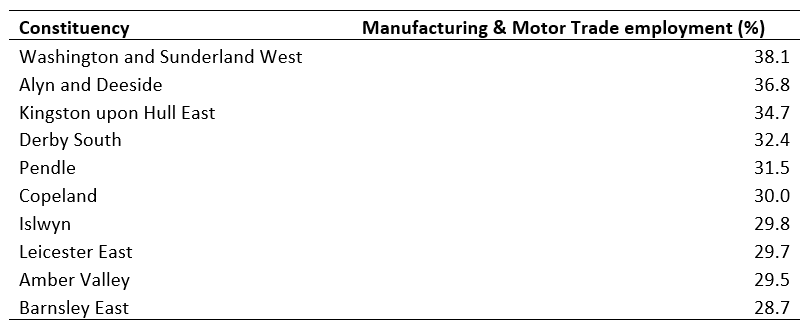

The map below shows the proportion of employment in manufacturing and motor trades for each Parliamentary Constituency. Regions with high dependence on manufacturing employment are particularly exposed to the changes described above. Some constituencies in the North East, Midlands and Wales have over 30% of their employment in manufacturing.

Manufacturing and motor trades employment in 2017 by Parliamentary Constituency[1]

[1] The map plots employment in the manufacturing and motor trades industries as a share of total employment in the Constituency in 2017, using data from the ONS Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES).

Manufacturing and motor trades employment in 2017: Top 10 Constituencies

Transport

The transport sector operates hand-in-hand with manufacturing: a decline in the manufacturing sector caused by technological disruption will also put pressure on the transport sector. A particular threat facing workers in the industry is driverless vehicles. In spite of significant developments in trialling autonomous vehicles, the timing of this shift and the proliferation of the technology remains unclear. Employment in the sector has settled over the last decade.

This is likely to change. Transport is particularly susceptible to Brexit where, for example, just two extra minutes spent on each vehicle at the border could triple queues on the M20 and see nearly 5 hours of delays in Kent at peak times. This may result in a vicious circle, impacting on manufacturing costs which translate back to the transport sector. The double disruption will bite vulnerable transport workers twice over. We note that a high proportion of transport workers, logistics and couriers are precarious workers outside the basic floor of protection for employees. At the time of writing, the future of the additional protection afforded by some EU-based rights, including the Temporary Agency Work, Working Time Regulations and the Information and Consultation of Employees Regulations, is unclear. Early scoping suggests these protections are of particular relevance to this sector.

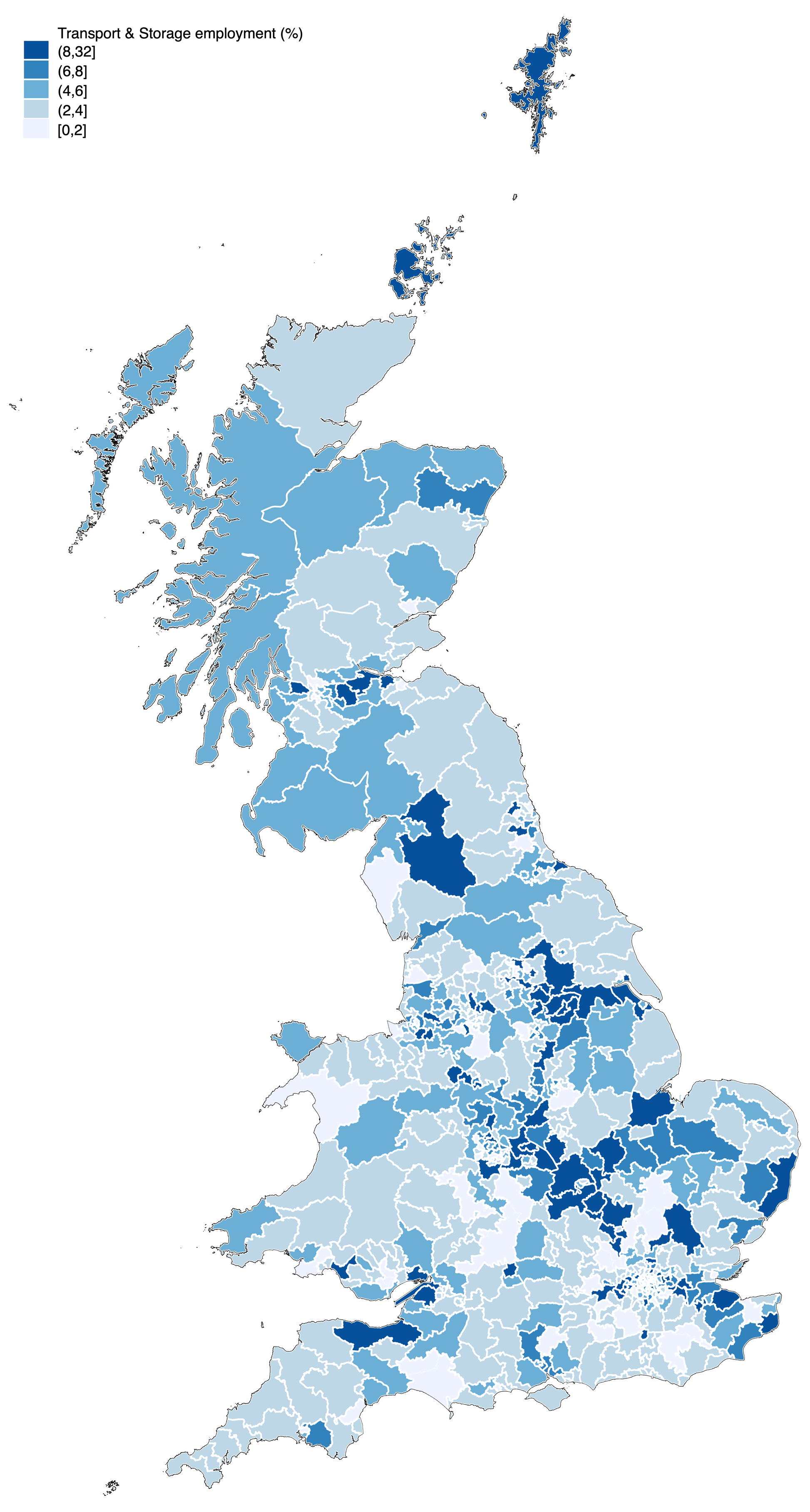

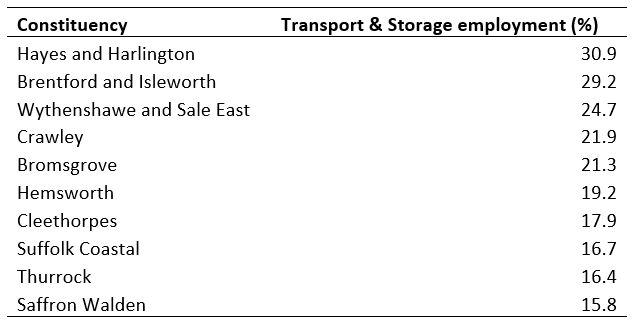

For more than half of Constituencies, transport and storage comprises less than than 5% of total employment. But many constituencies rely heavily on the sector, with as much as 31% of employment deriving from jobs in transport.

Transport and storage employment in 2017 by Parliamentary Constituency[2]

[2] The map plots employment in the transport and storage industry as a share of total employment in the Constituency in 2017, using data from the ONS Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES).

Transport and storage employment in 2017: Top 10 Constituencies

Retail

The retail sector has already undergone a series of major shifts as the way people purchase good changes from in-store to on-line. This has caused a move away from high-street jobs towards lower-quality warehousing and delivery jobs. On top of this, the sector is dependent on consumer spending which will reduce as real wages fall. Added trade costs could also push up prices which may filter through to the retail sector. The textiles, clothing and footwear industry will be among the hardest hit of UK industries, with Brexit likely to reduce the gross added value by up to 7%. Trust for London analysis notes that in-work poverty in retail appears to be growing.

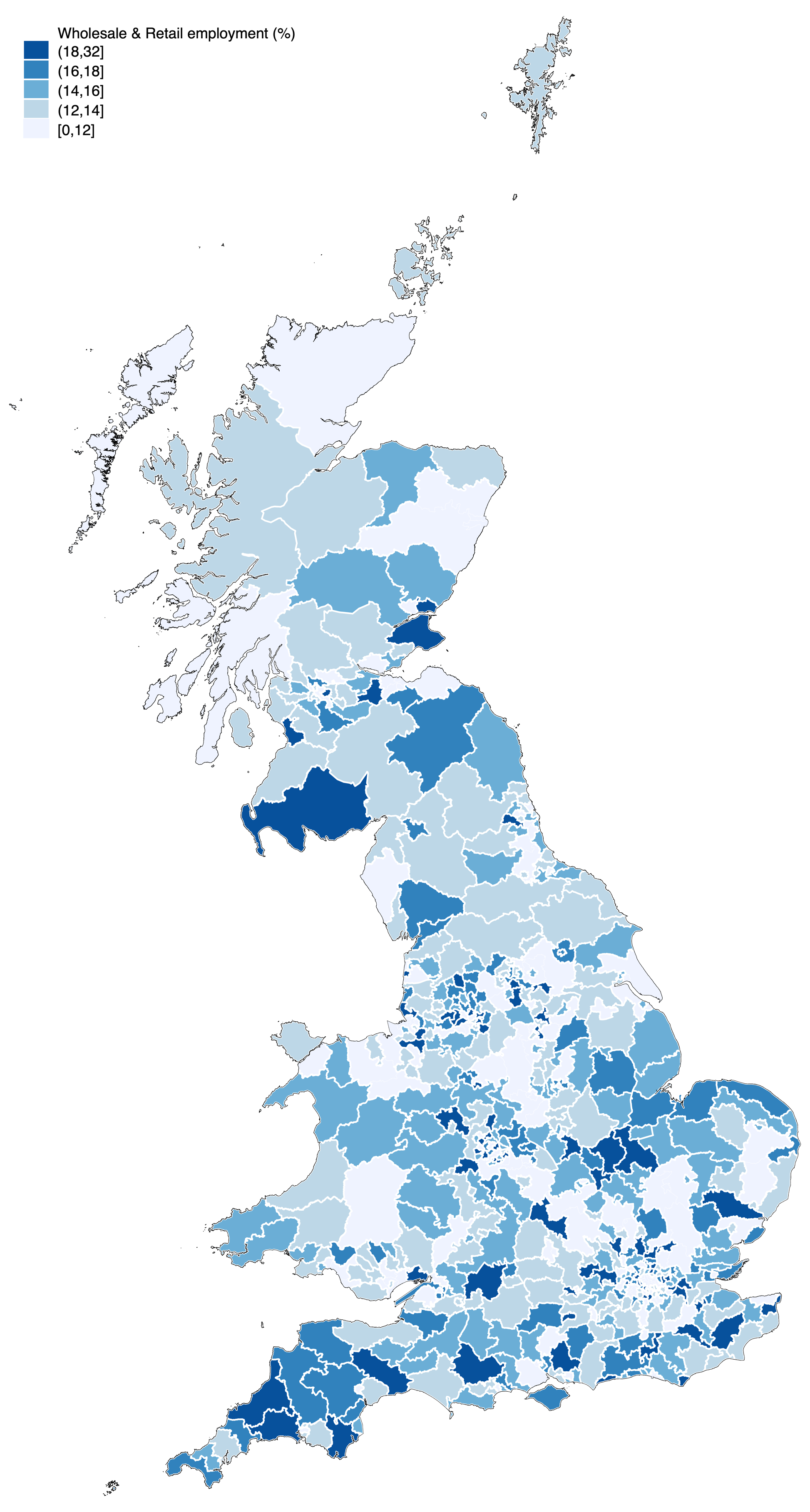

Wholesale and retail employment is above 10% for most areas of the UK. It is crucial to the UK economy, with the retail sector alone worth £92.8 billion in 2017. Yet some areas are still significantly more exposed than others, as shown in the map.

Wholesale and retail employment in 2017 by Parliamentary Constituency[3]

[3] The map plots employment in the wholesale and retail industries as a share of total employment in the Constituency in 2017, using data from the ONS Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES).

Wholesale and retail employment in 2017: Top 10 Constituencies

Conclusion

By looking at the effects of two major structural changes in the round we are able to identify two major challenges. First, that immediate downward pressure on wages caused by Brexit against the background of technological disruption will impact industries and regions extremely unevenly. In particular, there is likely to be a reduction in employment and an increase in in-work poverty in key sectors such as transport and retail. Low-skill workers in these sectors across the country are most exposed, facing a ‘double disadvantage.’

Second, Brexit is highly likely to dampen the adoption of technology and technological progress, at least in the short term. This will interfere with the progress of a main pillar of Industrial Strategy. At the same time, the UK’s resilience and ability to respond with agility to technological disruption will be reduced, benefiting our competitors. In both instances, the impact of No Deal Brexit will be more pronounced.

In these demanding circumstances, how can policy makers cope with immediate demands from the double disruption, whilst re-orientating the economy to address the underlying flaws that are the backdrop to the Brexit vote? We think that only bold and targeted policy-making will work. The need to create good new jobs and to facilitate the transition of workers must drive long-term planning. But the immediate area for attention should be critical social, economic and educational support for, and investment in, our most vulnerable communities and countering in-work poverty. This is not a tactical matter. These areas should be prioritised and integrated as we reposition good work to be at the centre of a ‘moral’ British economy.

The Good Work Plan is a good start and an excellent pointer. But to plan for a future of good work, we will need to extend our remit to all those things we discuss in this paper on top of emergency measures: training, reskilling, new job creation across the regions, immigration and trade by sector incentivising private investment, increasing public investment and opening access to finance. We will also need to discuss the infrastructure needed to achieve sustainable good work in our post-Brexit world, including how we pay for and administrate these measures. We anticipate that increased Government investment (including widespread use of beefed-up transformation funds across all vulnerable regions and piloting new types of incentivised private-public partnerships aimed at re-skilling workers) will feature heavily.

A comprehensive, forward-looking vision and strategy aimed at future good work is a prerequisite to addressing the twin challenges of double disruption. Whatever the outcome of Brexit, the best way to start this process is to draw from Germany’s Work 4.0 framework, and initiate a White Paper on the Future of Work.

This post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Breixt or the London School of Economics. It is an extended version of the article that appeared on LSE Business Review. For the full report and sectoral analysis please visit www.ifow.org and read here.

Christopher Pissarides is the Regius Professor of Economics at LSE, a professor of European studies at the University of Cyprus, chairman of the Council of National Economy of the Republic of Cyprus and the Helmut & Anna Pao Sohmen Professor-at-Large of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Anna Thomas is founding director of the Institute for the Future of Work (@_futureofwork).

Josh De Lyon is a Research Fellow at the IFOW and a PhD student in economics at Oxford University. He is also a research assistant in trade at LSE. He tweets @joshdelyon.

‘with a probable reduction in UK income per capita by around 8%’ is highly misleading. Read normally, that means that income per capita would fall by 8%. Following the link, one finds that in fact – just like the ridiculous Treasury propaganda – the figure derives from forecasts of per capita income in 2030 under the two scenarios – and the difference between them. This is obviously speculative, and one’s view on this depends greatly on how one sees EU membership – eg on whether EU regulation a boon or a bane etc etc.

Andrew

The article is saying that brexit will hit different parts of the country in differing ways as they are more/less reliant on certain high risk of disruption sections of the economy. Therefore simply focusing on doubts regarding income per capita forecasts is missing the point.

It is like championing the recent ‘recovery’, post the financial crisis, in that the distribution of the income growth was so keenly seen in specific regions not across the whole of the UK.

It is notable though that some of the above areas are listed as high risk for social disorder post brexit so at least someone in the civil service can review data. Just a shame they couldn’t persuade the policy makers to push investment into these areas.