There are plausible reasons to think that an early election is likely, writes Hudson Meadwell (McGill University). In this blog, he outlines the possible paths that lead there. The two most likely paths to an early election, in his view, are new deal-ratification-withdraw-early election or no new deal-withdraw-early election.

I expect that prorogation will eventually be ruled lawful (if not constitutional). Jonathan Sumption, a former Justice on the Supreme Court, in fact, raised this interpretation at the time that Johnson asked for and received royal assent. Two courts (English and Northern Irish) have ruled in the government’s favour, another (Scottish) has not. I believe the Supreme Court will not lift prorogation.

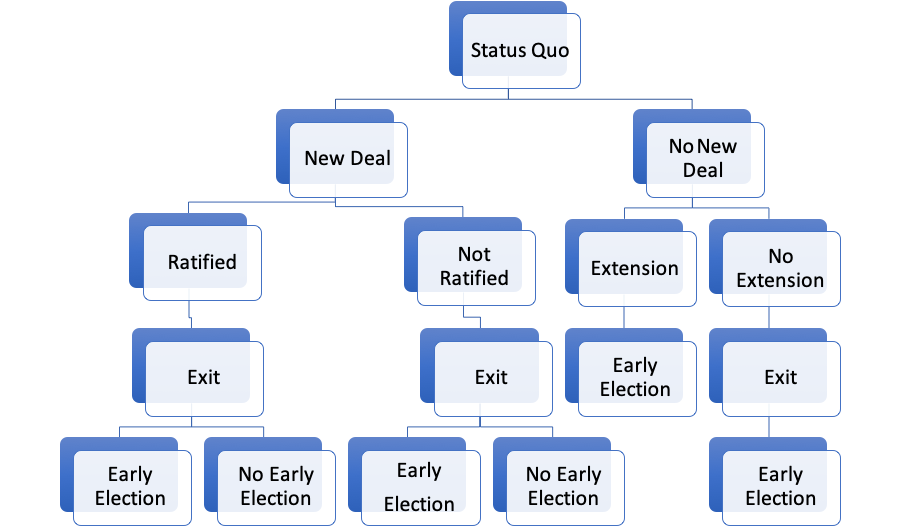

There are three salient features of the Brexit process at this post-prorogation stage: 1. Will there be a deal that the Conservatives will be able to present to Parliament for ratification? 2. In the event that a deal is presented in Parliament, will it be ratified or not? 3. Whether or not a deal is ratified, if presented, or there is no new deal, will withdrawal be followed by an early election and will an early election, if called, follow from a government motion or from an opposition no-confidence motion? The legislation that endeavours to compel the Conservative government to seek agreement from the EU for an extension, appears directly in the map below. But I don’t regard it as a basic feature of the Brexit process.

One organizational possibility does not appear in this map because it does not have much political feasibility – a referendum to approve a new deal, if one emerges. It could be mooted again in Parliament, perhaps as a condition introduced by some members on ratifying a new deal, but it is not likely to have much political traction. As an option of close-to-last resort for Remainers, this suggests that ‘Remain’ is in danger of losing political purchase altogether. And another (not a second) referendum after an early election, if it were to happen, looks not to be about remaining in the EU at that stage but about rejoining after leaving.

Another possibility, noted here but not discussed further, which is attractive to Remainers is to move to to revoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. It’s very late in the process to see how revocation might happen.

The resulting map looks like this:

Take the right-hand side of the map first, beginning with ‘No New Deal’. I have mapped out two further outcomes: an extension of the withdrawal agreement and withdrawal (exit) without an extension. It is still possible, if we get to that point, that the Conservatives will be able to finesse the force of the legislation mandating a request for an extension. Failing a finesse, and an extension is granted, I will assume that an early election will follow. Jeremy Corbyn will do what he has said in the Commons he would in the event of an extension and support an early election whether through putting forward a no-confidence motion or through supporting a government-initiated motion for an early election.

I also regard an early election as a highly likely outcome if withdrawal without an extension occurs. The Conservatives will support an early election and the opposition will have difficulty justifying the refusal to support a government motion. No-confidence is another route to an early election and there may be incentives for the opposition to bring such a motion, depending on public reaction to the early days of withdrawal. In either case of an early election after withdrawal, I expect the Conservatives to campaign on having delivered Brexit. In the event of an early election following from an extension, I would expect the Conservatives to campaign aggressively around the claim that the popular will is being stymied and subverted, drawing on the rhetorical trope of ‘the People versus (everything and everyone else)’.

Now take the left-hand side of the map which begins with the presentation of a new deal to Parliament. Any new deal is likely to be an iteration of the May agreement whatever Conservative leaders may have to say publicly to distance themselves from that agreement. My view is that if a new deal is presented to Parliament, having been negotiated by the EU, and in the process approved by Ireland, it will be ratified. However, in an early election that likely will follow, whatever the substance of a new deal, Conservatives will face trade-offs between satisfying hard-Brexit parts of their electoral support and membership base and other parts of the electorate, who prefer a new deal to no deal. The Conservatives can campaign on a new deal and I think this can be said without knowing the precise details of any new agreement. But it would be a different campaign than one that would follow withdrawal with or without an extension (the right-hand side of the map).

Boris Johnson may not be completely disingenuous when he claims that a longer-than-usual prorogation is needed to prepare and present the government’s parliamentary agenda under his leadership. This is a sign that the Conservatives are imagining the possibility of an election campaign not driven exclusively by Brexit. This is most likely, in my view, under a scenario in which the government presents a new deal to Parliament and it is ratified. In this scenario, they are helped if they can campaign on a forward-looking agenda, without an exclusive focus on Brexit, especially one that introduces other issues where they can compete with opposition parties.

It is very likely that the Conservatives have been anticipating several scenarios, whether it is taking forward a new agreement and defending it as the best possible under the circumstances, and one that will mitigate the costs of exit when compared with a hard exit, or defending a no-agreement exit. I would expect the latter campaign to be more aggressively about Brexit. This is the election in which the Conservatives may have to fall back on the hard-Brexit base.

So, there are plausible reasons to think that any early election is likely to be to dominated by a single issue, especially under no extension and withdrawal. Nevertheless, a national election will not be a surrogate second referendum. While there may be a single organizing issue going into an election (to varying degrees, as above), an election campaign is going to prime those features of British politics that the referendum campaign did not, or at least not fully, such as territorial and national politics. This holds under all scenarios. The election will be fought on a territorial basis; it may be constituency by constituency, but this aspect of electoral politics should still prime territorially-related perspectives and concerns.

Johnson’s and Cumings’ trope, variations on ‘the people versus Parliament’, may mobilize voters’ dispositions in parts of the electorate but not all parts. This is another reason to suggest that the Conservatives, under circumstances outlined above, may think themselves better off by establishing an agenda when Parliament returns, so that they can campaign outside of England on something other that Brexit and appeals to the ‘people’. Populism in Britain runs up against this limit – not all of Britain is English. However, the sheer size of the English electorate has made populist nationalism an attractive political frame in response to the erosion of English dominance.

I would expect a mixed Conservative strategy in terms of targeted messages in an election, which is not unusual. However, thus far, the Conservatives have not managed their electoral dilemmas and this mix very well, perhaps because they have no direct control over what kind of election they should commit to. They have had to hedge their bets because what comes next may be in the hands of the EU.

The two most likely paths to an early election, in my view, are: new deal-ratification-withdraw-early election or no new deal-withdraw-early election. Not even knowing the details of a new deal, I would suggest a new deal has a better chance of being ratified than any of the May agreements. If ratified, an early election will follow, but there may be some jousting as to how that happens, whether by a government motion with opposition support, or a no-confidence motion. Since I am not convinced that the legislation to enforce a request for an extension will in fact have force, if there is no deal, I expect that withdrawal and an early election will follow.

The largest question obviously is whether a new deal will emerge or not. My expectation is that there will be a new deal presented to Parliament, it will pass, and exit will occur, followed by an early election. A new deal is a superior option to no deal, that is, it is in the organizational interests of the EU and the Conservative party. If the EU can strike one agreement, it can strike another, under ‘exceptional’ circumstances. It may appear more of a comedown for the Conservative Party, but the party under Johnson has been signalling since his selection that it can take on another agreement and exit with a deal.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image: CC0 Public Domain.

Hudson Meadwell is Associate Professor of Political Science at McGill University.

And where does implementing the 2018 recommendations of the Boundary Commission fit into all this?

How about you write your own article all about the Boundary Commission and its recommendations, rather than polluting everyone else’s articles with your singular obsession?