One of the results of the recent illiberal turn in European politics has been growing state capture that leads to the breakdown of the supervisory institutions of democracy. In this blog, Roch Dunin-Wąsowicz (LSE) argues that some of Europe’s authoritarian populists have succeeded, or are planning to, take control of both public and private media, as well as civil society, academic and state-adjacent sectors of the economy. This return of corporatism to European politics is one of the symptoms of the breakdown of substantive democracy on the continent.

Nowhere has this been more apparent than in Hungary where the governing Fidesz has essentially colonised the state apparatus, the media, the academy, and some crucial private enterprise. In Poland, Law and Justice have turned the public service broadcaster into a propaganda device, made strides in taking over the judiciary, and speak of private media take-overs, as well as fostering a “new economic elite”. Even in the UK, the independence of the judiciary and public media are questioned by critics of liberal democracy.

This weakening of substantive democracy is exemplified by the erosion of what Keane calls monitory democracy. Firstly, this entails the deconstruction, or takeover, of institutions of public scrutiny, which were designed to chasten and control executive power. Periodic elections still take place, but the state apparatus has become the hostage of majoritarian political rule – the judiciary and the civil service are undermined in the name of sovereignty of “the people”. By deconstructing the monitory institutions of democracy illiberal governments are thereby hollowing out the state. And, while excessive technocratic governance has been invoked as an example of post-democracy, the strength of institutions existing for the public good had largely been built on the expertise and professionalism of a bureaucratic strata somewhat shielded from politics. For example, since 2015, Law and Justice managed to successfully replace the upper echelons of the Polish civil service by cancelling merit-based competitions for high-level posts and replacing them with ministerial appointments. Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal was soon hijacked, in contravention of the country’s constitution. Since then a few partially successful attempts have been made to take over the Supreme Court – only partially stymied by the EU. In a similar vein, in 2019, Viktor Orbán’s government suggested the creation of a parallel court system staffed with judges selected by the justice minister – it claimed that courts are an internal manifestation of state power and cannot be independent from the executive. Hungary has since backtracked from this particular reform under pressure from the EU. However, if implemented these new administrative courts would allow the Hungarian government to have jurisdiction over electoral law, political protest, and public corruption, stripping the judiciary of its oversight functions. In the UK, the courts have become embroiled in the battle over Brexit, and while the government has been reluctantly abiding by their rulings, ardent supporters of a “hard” Brexit have whipped up public anger with the Supreme Court, undermining its independence.

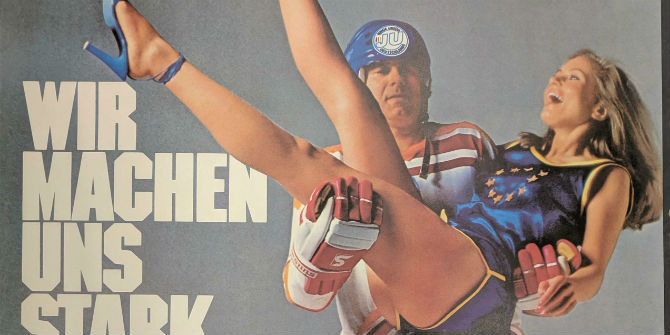

Image by Gphgrd01, (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The second feature of erosion of monitory democracy is the co‑option of the media, first public and then private, which in Keane’s view are part of the “power-scrutinising mechanisms” between the executive and society at large (2011). In 2018, all pro-government media outlets in Hungary were subsumed under newly formed conglomerate equipped with immense resources, while many independent ones have been dismantled through hostile takeovers or pushed onto the web only. In the World Press Freedom Index Hungary is now classified as “partly free”. Likewise, since 2015, Poland’s public radio and television have been a veritable mouthpiece for the government, prompting OSCE election observations in 2019. In Britain, politicians associated with the hard right continue to castigate the BBC and threaten its independence.

The third, newly-emerging component of the erosion of monitory democracy is the ever more explicit attempt to create new elites in civil society, academia, and in the economy loyal to a particular political caste. This justification for weakening democracy is built on a distinctly populist discourse. Those who are seen as the true representatives of the people are rewarded for their ideological conviction, rather than merit. In places where such new cadres are installed, evidence-based policy is replaced by policy-based evidence, often with disastrous consequences for the non-governmental sector, higher education and private enterprise. In 2019, Hungary has brought the country’s top research institutions under its control, and almost completely pushed out the Central European University out of Budapest. In Poland, the government has been implementing a policy of “re-Polandisation” of the banking sector, which it now wishes to extend to private media. Also the project of Global Britain is designed to benefit a narrow economic elite while disregarding the risk to the millions of working people whose jobs are dependent on the a close relationship with the EU, many of whom are Europe migrants themselves.

The above illiberal political projects are underpinned by a certain kind of populist new elite discourse, whereby selected representatives of the majorities that stand behind those in power should be rewarded for their loyalty. Until now in each of the country cases discussed above, in has been the strength of certain monitory institutions, scrutiny of civil society, and interventions (or mere presence) of the EU, that to different degrees have thwarted this hostile takeover of state and society. We must build on these positive experiences to protect against the further abolition of the institutions of monitory democracy that have become so important to modern rule of law systems.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. “The future of European democracy” series is part of an on-going collaboration between the Visions of Europe project at the London School of Economics and the Europe’s Futures programme at the Institute of Human Sciences in Vienna.

Decent short article but I think you’re understating the most extreme case – the UK. Poland and Hungary may be busily entrenching authoritarian populist gov’t in place of the nation’s ndependent institutions but the UK is far and away the European society most at risk.

Deregulation (e.g. loosening fiscal policy, sectioning off choice NHS services for privatisation), isolation (e.g. from moderating EU consensus), legislation (e.g. hobbling the BBC, throwing out human rights) – the UK is in big trouble.

I agree that the UK is now in serious trouble. What is the secret agenda of Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings? We will soon find out, and my guess is that it will not be pleasant.

The UK has become somewhat complacent. There is the old historical shibboleth that “the UK has not been successfully invaded since the Norman Invasion in 1066”, and so can manage quite well on it’s own. My guess is that, without the power of the EU behind it, the UK will increasingly drift into the orbit of a Trumpified USA, with all the defects the current impeachment process is currently revealing.

Now is the time above all to remember “the price of liberty is eternal vigilance”.

Britain has voted to leave the EU, in part, to extricate itself from democratically unaccountable interference in the internal affairs of this country.

‘Monitory institutions’ that cannot be held to account by the electorate are, however well intentioned, necessarily authoritarian and anti democratic.

Unelected supranational governments reliant on majority decisions by member states rather than empowerment through democratically agreed manifestos, voters powerless to exercise any control, themselves require ‘monitory institutions’ but of those, with regard to the eu, un, none exist.

The most recent exercise of the voter’s will, in this country, may very well usher in the rolling back of ‘Blair’s Britain’ (too much government, unreformed and outdated constituency boundaries, an unreformed civil service, too much quangocracy, an over mighty judiciary, bloated parastatal corporations living off barely competed public sector contracts, an unreformable NHS, public sector broadcasting for the few not the many), and not before time.