Supporters of populist parties are often assumed to have low levels of political engagement. Drawing on a new study of voters in nine European countries, Andrea L. P. Pirro and Martín Portos argue that this perception is largely misguided. When non-electoral forms of political participation are considered, those who vote for populist parties exhibit higher levels of engagement than supporters of non-populist parties.

Populism is all the rage. Few European countries remain immune from populist parties (we now count Malta and Ireland) and in at least a handful of countries (e.g. Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, and Poland) populist parties hold the majority of seats in national parliaments. The recent performances of Vox in the 2019 Spanish general election and Chega in the 2021 Portuguese presidential election have also put an end to ‘Iberian exceptionalism’.

While largely associated with radical-right politics (short for ultranationalist and socio-cultural exclusionary positions on immigration and with regard to ethnic minorities), Europe has also seen a surge of left-wing variants of populism, as illustrated by the once-radical Syriza in Greece and the progressively more institutionalised Podemos in Spain. For the sake of clarity, we consider populism as a set of ideas emphasising ‘the people’ as the linchpin of any rightful political goal and decision; criticising ‘the elite’; and capitalising on a sense of (real or perceived) crisis. Populist parties and movements ultimately seek to mend the degrading of popular sovereignty – the latter allegedly corrupted by treacherous and self-serving elites. From this perspective, populism resembles an empty shell that can be filled with ideologies as disparate as socialism or nationalism.

Overall, we have become familiar with the ideology of populist parties as well as the drivers of their vote, but a significant gap persists regarding our understanding of what populist supporters do besides the simple act of voting. Populism is generally linked to mistrust and apathy, and common wisdom suggests that populist supporters do not engage in politics – or are, at best, reluctantly political. In a recent study, we were interested to know whether populist voters engage in forms of non-electoral participation, such as protest activities, digital activism, or boycotts. At the same time, we sought to answer questions related to the role played by social values in populist supporters’ participation as well as the influence exerted by attitudes on economic redistribution and immigration.

We analysed the level of non-electoral participation of left-wing and right-wing populist voters drawing on a survey conducted in nine European countries (France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom), with a representative sample of roughly 2,000 individuals per country. Looking at the range of non-electoral participation activities (which included contacting politicians, signing petitions, demonstrating, striking, damaging public goods, clashing with the police, and using social media for political purposes, among other activities), we came to five main conclusions.

First, populist party voters tend to engage politically more than non-populist party voters. Populist parties therefore foster anti-establishment but not apolitical views. Their ‘unpolitics’ leads to full engagement in politics since they also prompt grassroots mobilisation. This finding echoes the burgeoning literature on ‘movement parties’ as hybrid organisations operating in both the electoral and protest arenas. This observation calls attention to the investments in grassroots politics by populist left and populist right parties – and the broader prospects they might offer in terms of political socialisation.

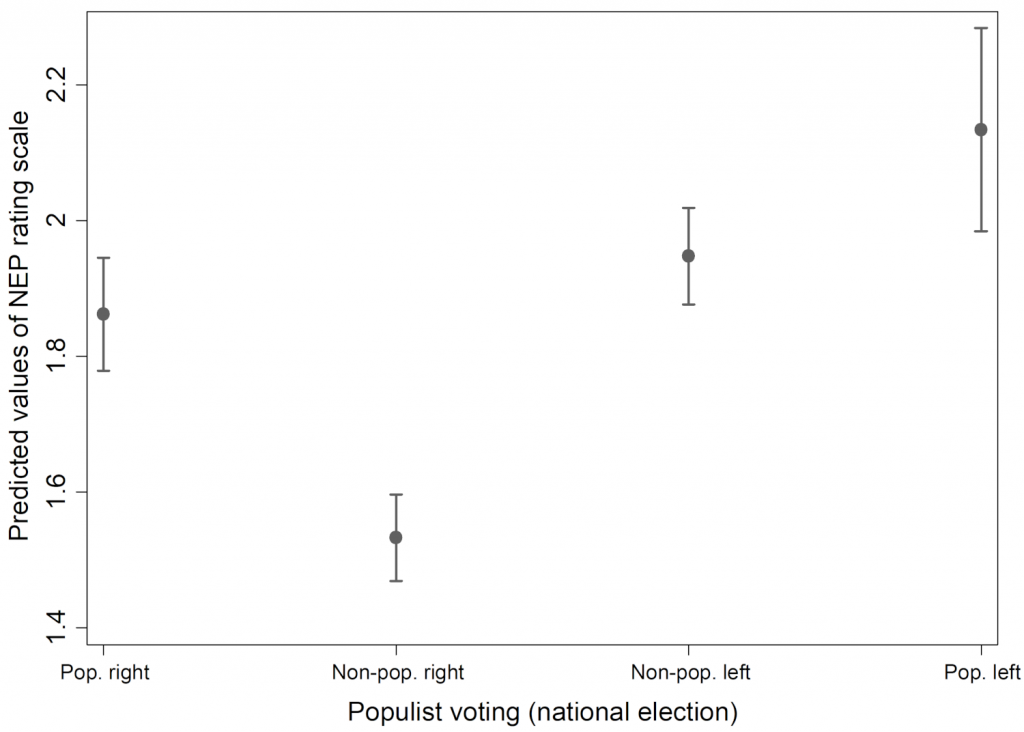

Second, left-wing populist party voters generally participate more than right-wing voters. However, right-wing voters are not an entirely demobilised set. Indeed, as Figure 1 below indicates, populist right voters engage more in non-electoral activities than non-populist right voters, and generally as much as left-wing voters. The populist right has thus come to rely on a reserve of ‘all-round’ activists, prompting us to reconsider the long-standing notion that grassroots activism is the sole preserve of left-wing politics.

Figure 1: Predicted values of non-electoral participation as a function of populist vote

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in West European Politics.

Third, in our attempt to unearth the social values underlying the levels of political engagement, we found that left-wing voters holding libertarian views and populist right voters holding authoritarian views are those that mobilise the most at the non-electoral level. While confirming progressive values as an important driver of participation for the left, our findings show that populist right-wing authoritarians do not necessarily subscribe to forms of ‘orderly’ or conventional participation. Populist right-wing voters sharing authoritarian views value casting ballots in elections as much as other forms of political participation.

Fourth, when it comes to the issue of immigration, populist right party voters holding negative views on migrants tend to mobilise more than non-populist right party voters. At the same time, positive views on migration tend to feed into the non-electoral participation of populist left voters. This finding resonates with the ideological profiles of populist parties and confirms the prominence of a populist/non-populist divide for engagement beyond the ballot box.

Finally, when it comes to economic redistribution, it is interesting to see that populist right voters embracing redistributive views tend to mobilise as much as left-wing voters – whether populist or not. We see this result in line with the progressive – though not univocal – shift of the populist right from champion of neoliberalism to torchbearer of economic paternalism.

These conclusions have a number of implications for our understanding of populism. In a context of declining party membership, populist parties have supplanted traditional parties, investing in their presence on the ground and constant campaigning. The alternative prospects for political participation offered by these parties are consistent with the images of large-scale anti-austerity mobilisations in Greece and Spain, but also the increasing relevance of grassroots politics in the populist right’s playbook – as exemplified by the storming of the US Capitol by Donald Trump supporters earlier this year.

So, while populist supporters may be disenchanted with mainstream parties and politics, they are far from disengaged. We thus suggest there should be more focus in future research on developments outside electoral and institutional arenas, and that political participation should return to the centre of our attention. Allegiances and forms of engagement are changing – and this holds particularly true for populist right parties that can now rely on a reserve of highly-engaged activists mobilising beyond the voting booth.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in West European Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: News Oresund (CC BY 2.0)

1 Comments