By Bruno Casella (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)) and Lorenzo Formenti (International Trade Centre (UN/WTO))

By Bruno Casella (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)) and Lorenzo Formenti (International Trade Centre (UN/WTO))

By spreading value added, employment and technologies across multiple locations, Global Value Chains (GVCs) have been a key driver of economic transformation. In Africa, however, participation to GVCs has not always delivered the expected development outcomes. The “Great Reset” imposed by the pandemic is also an opportunity to rethink the development strategies of African countries, towards a GVC participation model that is not solely wealth-enhancing, but also shock-resilient and environmentally-sustainable.

GVC development in historical context.

The last half-century of international production has seen a unidirectional travel route: more international production and more GVCs. A simultaneous movement towards fragmentation of tasks and geographic distribution has been the underlying force shaping modern globalisation. Increasing resort to outsourcing and hybrid modes of governance such as non-equity has further expanded the possibilities of GVCs. Unbundling, offshoring and outsourcing were the powerful mix that enabled GVCs to take a dominant role in global investment and trade over the last 30 years. From a development perspective, the GVC boom has been instrumental in spreading value added, employment and technologies across multiple locations at different stages of development. This has opened up opportunities for accelerated “catch-up” and convergence between economies.

The GVC wave has not spared Africa. Roughly in line with the other developing regions, inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) to the continent have grown by a factor of 20 in 20 years (1990-2010, slowing down only in the last decade). Nevertheless, the scale of global investment flows in Africa, at 3% of the total, is still low. The distribution of investment across the continent remains uneven, with the three largest recipients (South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria) hosting almost half of total FDI stock. FDI is poorly diversified downstream, with mining covering almost 20% of the total value of cross-border greenfield investment – a share significantly higher than in Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean (2% and 10% respectively).

Critically, the development benefits associated with economic integration and FDI in Africa have not fully materialised. Participation in global value chains has caused some degree of dependency on a narrow technology base and on access to value chains coordinated by multinationals for limited value-added activities. This has been the case in most African Least Developed Countries (LDCs), where GVC participation remains limited to exports of unprocessed commodities with low value retained locally.

The COVID-19 perfect storm.

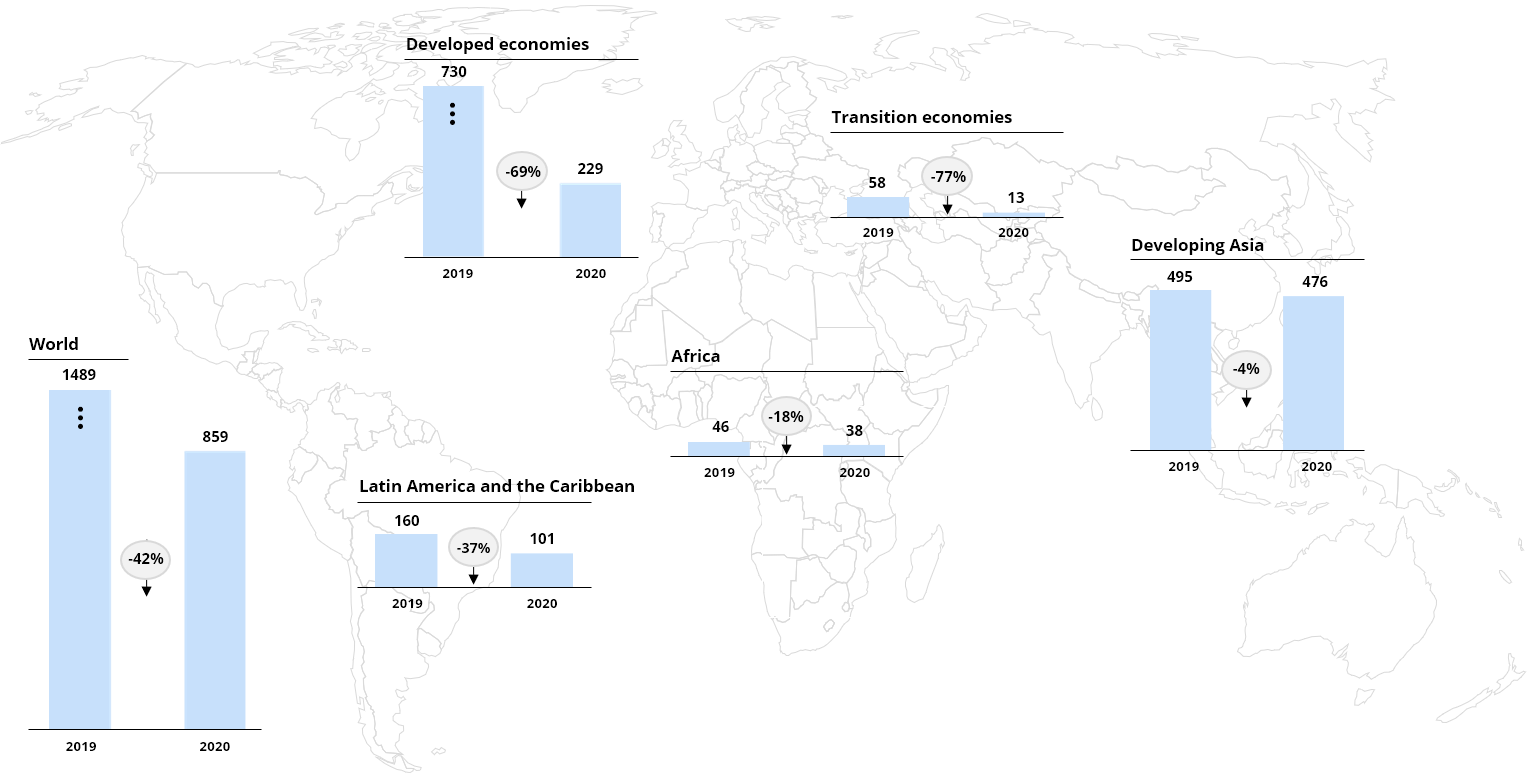

It is in this context that the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to strike a perfect storm in the system of international production, adding to ongoing mega-challenges, such as the new industrial revolution, growing economic nationalism and the sustainability imperative. UNCTAD forecasts pointed to a drop in global FDI inflows of 30 to 40 per cent in 2020 (UNCTAD, 2020). The preliminary figures for 2020 confirm this negative outlook with total global investment, and investment to Africa specifically, down by 42% and 18% respectively compared to 2019 (Figure 1).

Source: Authors based on UNCTAD (2021). Right click ‘open image in new tab’ to expand.

Note: Data 2020 are preliminary estimates.

***

Longer term, flattening demand, policy uncertainty and the call to switch to more resilient and locally-focused supply chains will exert further downward pressure on global production networks, with heightened risks of GVC dismantlement. The quest for resilience through more localised and regional supply chains may affect in particular efficiency-seeking FDI, , traditionally one of the main routes into global production networks for poorer countries.

The glass half-full.

With shrinking public spending and low business confidence, African countries will be confronted with the “old” issue of reaping the benefits of value chain participation within the “new” context of a redefining globalisation. Faced by unprecedented challenges, governments are forced to fundamentally re-think their GVC development strategies.

This is not necessarily bad news. With the narrowing of the North-South offshore development channel, the South-South route – including through the consolidation of regional value chains – gains further, reinvigorated momentum. Efforts of trade liberalisation in the region, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), coupled with conducive investment policies, can help regional diversification by mitigating dependency from Western markets, capital and technologies and by stimulating structural transformation, for Africa and by Africa.

Regionalisation is not the only ammunition to counter the hollowing-out of traditional GVCs. The growing demand of low- and mid-range consumer goods in emerging markets, which are usually easier to access due to less stringent technical requirements, opens up new opportunities for low-cost producers.

The diversification of the supply base to build resilience may lead to a relocation of activities from “Factory Asia” to alternative low-cost manufacturing hubs within the continent. Emerging export-led clusters, such as the garment and textiles industry in Ethiopia and Madagascar, may thrive under these new circumstances.

A whole new set of opportunities relates to increased digitalisation. If, on the one hand, digitalisation further amplifies the value-added gap between a bulk of increasingly commodified, low-cost activities and a few highly strategic, knowledge- and technology-intensive ones, it also improves access to global markets, particularly for small businesses. Developing technology districts, such as the emerging ICT sector of Rwanda, may help African countries tap into these trends and position themselves as global providers of high value-added services (e.g. mobile app development) that are increasingly delivered remotely.

Similarly, in response to GVC reshoring and divestment, countries should move from specialising in tasks to developing fully integrated clusters by nurturing local entrepreneurial ecosystems in promising niches. This is the case in the audio-visual sector in Lagos, Nigeria, where local firms are establishing market links with global streaming platforms for original content.

Environmental degradation and the fight against climate change will push international production to comply with the aforementioned sustainability imperative. The green economy is emerging as an attractive venue for upgrading in global value chains. In the agri-food industry, changing consumer preferences for environmentally-friendly products, such as single-origin and certified commodities, provide new avenues for greening value chains and capturing value locally. The adoption of voluntary sustainability standards in buyer-supplier relationships, such as those in the cocoa value chain of West Africa, may lead to significant increases in crop productivity and farmer incomes, while also helping mainstream better environmental practices across the continent.

***

Given the importance of GVCs for post-pandemic recovery, economic growth and job creation, and for the development prospects of African economies, policymakers need to clearly leverage these opportunities to rethink the GVC development strategies of African countries, in ways that help them to embrace the new trends of globalisation.

References

UNCTAD (2021). Global Investment Trends Monitor, No. 38, January 2021. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD (2020). World Investment Report 2020: International Production Beyond the Pandemic. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Bruno Casella is senior economist at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Investment and Enterprise Division.

Lorenzo Formenti is Associate Sustainable Development Officer at the International Trade Centre (UN/WTO)

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.