by Riccardo Crescenzi (LSE) and Oliver Harman (Oxford)

by Riccardo Crescenzi (LSE) and Oliver Harman (Oxford)

Upgrading enables firms, countries, or regions to move into progressively higher value activities in GVCs in order to increase the benefits (e.g. security, profits, value-added, capabilities) from participating in global production. A recent LSE study for the Hinrich Foundation shows how countries upgrade in different forms representing opportunities for decisionmakers in Asia.

Countries upgrade in GVCs in different forms. In Asia, Vietnam represents one trajectory, its economic model led by FDI but focused on assembly tasks that depend on imports. The country shows a strong involvement of foreign MNEs in its economy. By contrast the Republic of Korea followed a different trajectory. Here the country experienced a much larger role for domestic MNEs, and the economic model is more dependent on the exports it provides others. Both, to many, are deemed successful cases of development in their own right, highlighting the multiple potentially beneficial pathways to GVC involvement in Asia. What matters is if the pathway is right for the technological and socio-economic context — not all countries achieve this.

When considering this context, there are two broad pathways which regions can upgrade, both horizontally and vertically. The former — horizontal upgrading — refers to the development of a new GVC product or industry in a region that is related to an existing area of specialisation of the local economy. For example, the manufacturing of mobile phones may follow from existing production of laptops. Horizontal upgrading includes ‘entry into the supply chain’ upgrading that is the initial participation of firms in a local, regional, or global value chain.

The latter — vertical upgrading — offers a new function for the local economy; for example, R&D, or marketing, logistics, headquarters management, and perhaps production in an existing value chain. If horizontal upgrading describes a movement from laptop production to mobile phone manufacturing, vertical upgrading describes the movement from laptop production to laptop design. A particular form of vertical upgrading is backward linkages upgrading. Local firms become active in an industry supplying goods and services to an MNE in a foreign country already engaged in an existing value chain.

The types of linkages and the direction of upgrading are important to consider. Economies can upgrade through forward and backward linkages. Forward linkages, also known as downstream linkages, refer to linkages with firms further along the value chain; that is, firms closer to final goods or eventual export. Backward linkages, also known as upstream linkages, refer to linkages closer to suppliers or initial goods, or creation of services. Upgrading does not necessarily mean moving upstream or downstream. Rather, it is the process of climbing up the value chain in terms value added and skills.

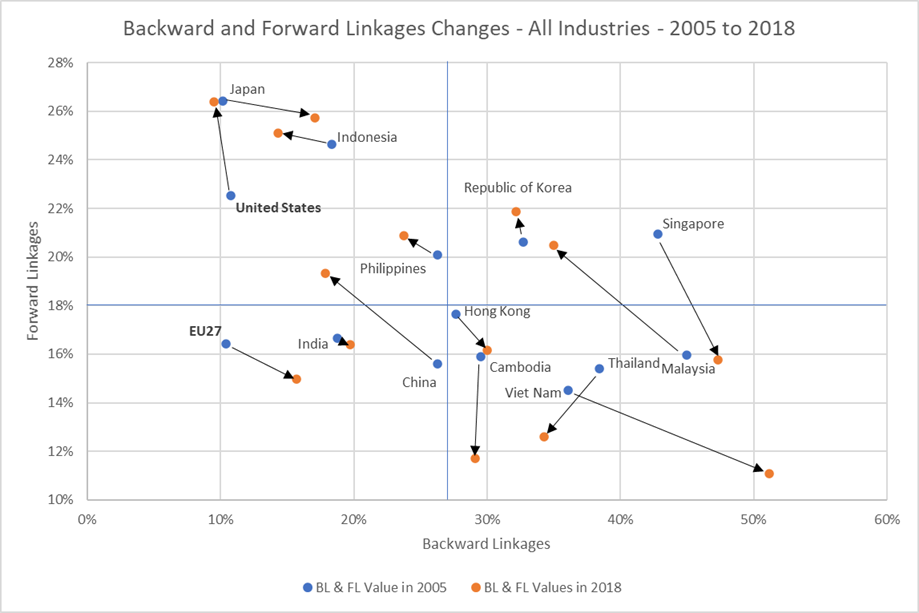

Figure 1 makes it possible to visualise the diversity of possible patterns to upgrading in terms of backward and forward linkages. Backward integration is captured by the country’s vertical specialisation share, measured by the import content of the country’s exports. Further to this, a country also participates in GVCs as a supplier of inputs used in foreign countries’ exports. Hence it is important to account for the share of exported goods and services which are used as intermediate inputs in other countries’ exports—that of forward integration. The combination of these two shares offers a first description of an economy’s participation in GVCs. This contribution is both as a user of foreign inputs—upstream links, that of backward participation—and as a producer of intermediate goods and services used in other countries’ exports; that is—downstream links, that of forward participation.

Figure 1 below shows the position of a set of Asian economies covered by the OECD Tiva indicators in terms of backward and forward linkages for all industries. Backward and forward integration in 2005, represented by the blue dot, is compared with the current position, shown by 2018’s orange dot. Interestingly, no country records an increase in both backward and forward linkages over this period. This evidence is in line with evidence on ‘global stagnation’ of GVCs that predates the Covid-19 crisis.

On the contrary, Thailand – and, to a lesser extent, Cambodia – has decreased its shares in both measures of GVC participation; both have become generally less integrated over the past decade. A lot of evidence shows GVC participation facilitates economic development and subsequently, these countries may be losing out by decreasing shares. Public policy can help to reverse this outcome.

Figure 1 further shows another group of countries—comprised of China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the Republic of Korea (our initial example) — that increased their forward linkages while decreasing backward linkages. The economies in this group all rely less on imported value-added for their own exports but have become increasingly relevant in value generation in countries importing intermediate goods from them. For example, the significant movement recorded by Malaysia might reflect one of these two shifts. Either the country’s shift towards automobile component manufacturing, as inputs into final car construction, or the increase in oil and gas exports, as inputs into petroleum products. Similarly, it reflects the country’s shift into high-tech, with semi-conductor devices and electrical products all inputting into mobile devices, storage devices, and photovoltaic panels.

Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore and, more marginally, India showed a drop in forward linkages while increasing their backward linkages. Vietnam makes a considerable movement towards the bottom right corner, that being a larger share of backward linkages compared to forward linkages. This could be due to increases in the tasks for final stage assembly and seems to reinforce the specificity of this particular model of upgrading as discussed above.

For all examples, each country will be competing and trading on different comparative advantages; therefore, there is no ideal GVC direction with increases or decreases in linkages important to consider in local context. What matters is that policy decisionmakers are making active GVC-sensitive public policy and investment to encourage task-based specialities.

Early studies of GVCs observed nation states as being largely passive and restricted to facilitating the drawing in of lead firm investment. Yet today, there is agreement to act upon this aforementioned ideal and deliver on a more pro-active interpretation approach. Particularly evidence advocates for active mediation to advance national policy priorities and facilitate the coordination of actors. In addition, policymaking for GVCs should include designing and developing policy interventions for local development.

Understanding the position (and its evolution) of each economy is of central importance for the design of evidence-based GVC-sensitive policies, and this is the subject of our next piece.[4]

*****

This article is based on the Hinrich Foundation report, “Climbing up global value chains: Leveraging FDI for economic development” by Riccardo Crescenzi and Oliver Harman

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the GILD blog, nor the LSE.

Riccardo Crescenzi is a Professor of Economic Geography at the London School of Economics.

Oliver Harman is Cities Economist for the International Growth Centre Cities that Work initiative, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford, and Associate Staff at London School of Economics