With Covid rendering face-to-face, live simulations impossible, Hannah Kuhn and Gustav Meibauer adapted a simulation for remote learning in their political science course. They share with us the lessons they learned.

Different times require adapting old methods to new challenges and opportunities. In political science, simulations are an oft-used and effective teaching tool. However, due to Covid-19, live simulations are often impossible. Adapting them for remote settings poses difficult questions regarding planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Political science simulation activities differ in style and form, educational purpose, and implementation. Entire courses may be designed around simulation games, which may play out not only in the classroom but also in virtual environments. Such simulations often rely on substantial student preparation and may involve separate forms of assessment and evaluation. Smaller-scale simulation activities tailored to, for example, seminar-length exploration of specific concepts or skills, e.g. policy decision-making or diplomacy, are used in undergraduate as well as postgraduate settings. Simulations are often cited as being highly effective at capturing student attention, incentivising participation and collaboration, and improving student learning and knowledge retention. Political science simulation research has often focused on larger-scale designs involving considerable face-to-face interaction, both formally (in specific sessions) as well as informally (e.g. when students are encouraged to interact regarding the simulation content beyond the classroom setting). This is not only pedagogically sensible, but also realistic insofar as political negotiations in the real world rely on extensive face-to-face interaction in addition to writing or virtual sessions.

Simulations are often cited as being highly effective at capturing student attention, incentivising participation and collaboration, and improving student learning and knowledge retention.

Our MSc course, Cooperation and Conflict in the 21st Century, therefore usually includes a medium-scale simulation activity that lets students experience and experiment with key concepts and strategies of negotiation, bargaining, and international diplomacy. In previous years, this simulation proved an effective learning tool for a course focused on the practical and policy relevance of a wide literature on cooperation and conflict. This is placed within the course’s overall teaching approach, which aims to enable students to take an active role in their own learning, and to relate concepts they have learned through reading and discussions with their own intuitions, experiences and (future) careers. In late 2020, little could have been timelier for that purpose than simulating the Brexit trade negotiations.

Technology and time

However, Covid-19 restrictions made a face-to-face simulation, if not impossible, then unadvisable for our 70 students. Where initially adapting to the pandemic took the form of emergency measures, sometimes referred to as pandemic pedagogy, it soon required re-thinking (and, for many teachers, re-learning) political science pedagogy, course design, instructional methods, evaluation, and assessment. Correspondingly, we considered if and how to adapt our simulation – and what implications this would have for preparation, implementation, and student learning.

Two considerations stand out when transferring existing simulation designs to an online-only setting: technology and time. Technology may enable, but also hinder online simulations. Participants’ unstable internet connections can interrupt and delay discussions in situations where constant engagement in one-on-one negotiations is necessary or where contributions are strictly timed for reasons of fairness (e.g. an opening position statement). Software applications to manage large numbers of participants are available only with a licence, and not all standard software currently used in higher education is suitable for simulation set-ups. For example, it may be impossible for participants to switch breakout rooms themselves, share their screens freely, or keep chat conversations private. Students may feel that their negotiation success does not rely solely on preparation or strategy, but also on tech savviness. They may feel overwhelmed with the multitude of parallel communication channels. Importantly, this is often in addition to existing concerns around privacy, or access to silent spaces at their residence.

Technology may enable, but also hinder online simulations.

For teachers, online spaces are (or may at least feel) less easily controllable than face-to-face simulations taking place in a classroom. This relates to unclear expectations for online behaviour in general, but also to the availability of multiple parallel communication channels outside the teacher’s control or access (e.g. WhatsApp). A face-to-face setting entails clearer boundaries for where and how negotiations happen – mostly in the room and in direct communication. Online, students can (and often do) switch channels quickly and effortlessly. This can be beneficial and could even enrich face-to-face simulations. However, in an online-only simulation, instructors may sense a loss of control: they may feel overwhelmed with managing not only a complex set-up, but also the surrounding technology.

In addition, simulation activities are often time-intensive in preparation and implementation, whether online or offline. For students, they involve reading briefs, preparing roles, and perhaps interacting across multiple channels outside the (virtual) classroom. For teachers, they require drafting rules, planning procedures, conducting the simulation, and considering evaluation and assessment. This is problematic if these time-intensive tasks combine with other factors specific to an online environment, for example, managing technology, decreases in attention span, or contextual burdens (e.g. childcare when schools are closed during a pandemic), to make moving simulations online unattractive for students and teachers.

How it worked

Given the constraints of technology and time, we opted for a smaller activity facilitated through the Zoom breakout rooms feature that maximised student choice, flexibility, and bottom-up learning. Intended learning outcomes focussed on conceptual development around bargaining and negotiation theory: understanding, experimenting with, and reflecting on, for example, negotiation dynamics, positions and interests, leverage, or alternatives to agreement. We opted for a topical issue already in the news, which reduced expected preparation time: the Brexit negotiations. One week in advance, students were asked to sign up for a role via Google Docs. They could choose between playing the United Kingdom, European Union, or Northern Ireland. A one-page policy brief reduced the negotiation’s complexity to two issues: the level playing field and the Irish border. Students were to engage with the topic prior to the simulation in a discussion forum on the course webpage. In groups corresponding to the roles they were assigned, they exchanged arguments and strategies in preparation for the activity.

After an introduction in the virtual classroom, students were assigned to their breakout rooms with at least one of each of the three roles present to start negotiations, and with the shared goal of (some form of) agreement within 30 minutes. This set-up is similar to a Harvard Negotiation exercise. The breakout rooms were unsupervised, although students were told they could be joined by non-participating observers.

Notable differences emerged on negotiation processes, e.g. organisation of the agenda, tone, or technology use (some students successfully used the private chat function in their breakout room to make side-deals), as well as outcomes (all the way from no agreement to fully developed, technical language). Analogous to relevant literature, we infer that many students gained considerable content knowledge about Brexit specifically in preparing for the activity, which was not otherwise covered in the course. Immediately after the activity, students were asked to reflect together on what happened and why. Such reflective interaction can prove highly effective at incentivising student learning and retention, even after a short role-play activity.

Reflections

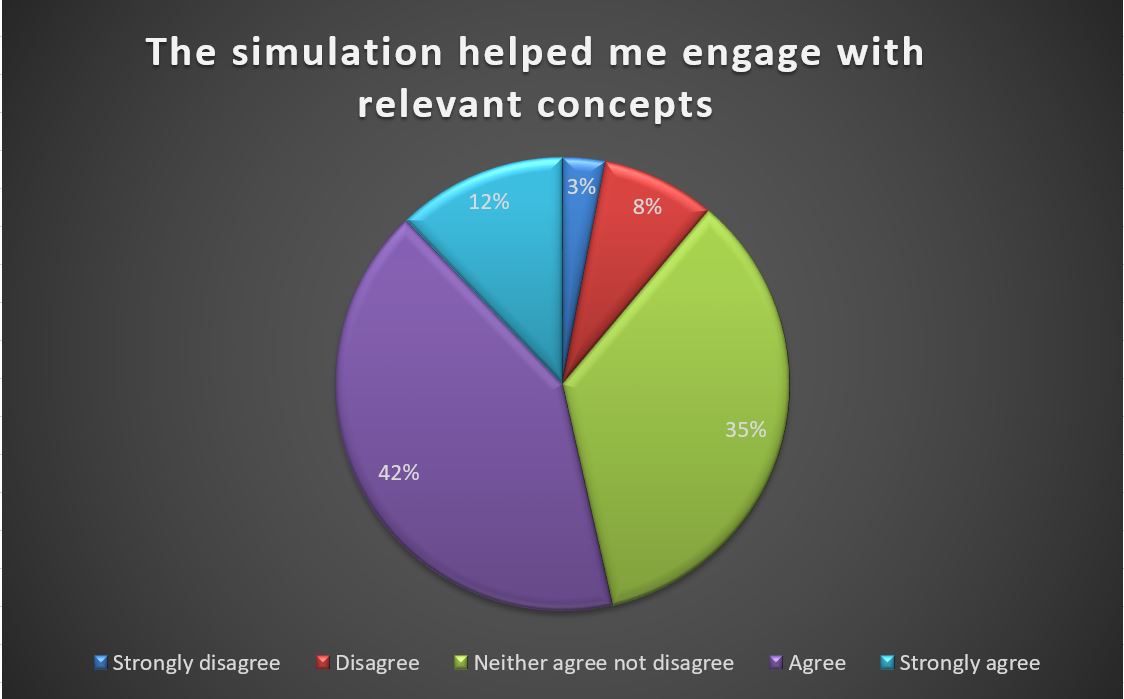

The post-simulation survey was answered by 65% of all course students and oriented loosely toward this model. 53% of respondents agreed that the simulation, in addition to and separate from their asynchronous preparation, helped them understand key concepts. That 11% of the students disagreed with this statement is not surprising: simulations do not appeal to all students and learning preferences. 35% neither agreed nor disagreed. This may relate to imprecision regarding what constituted the simulation. While we did not poll the reflection/debrief separately, we also did not explain to survey participants that we understood it as an integral part of the overall activity. Alternatively, it could also relate to the timing of the survey, which was made available immediately after the seminar to increase participation rates – it may be that knowledge had not yet been consolidated, for instance.

However, students also valued whole-class discussions, small-group work in breakout rooms, and shorter games of around five-10 minutes more highly as a type of classroom activity in synchronous seminars than longer simulation-type sessions. This provides a rationale for shorter simulation activities as one of multiple instructional tools in a longer course. Simulations are not a silver bullet in online teaching and need to be aligned with learning outcomes carefully.

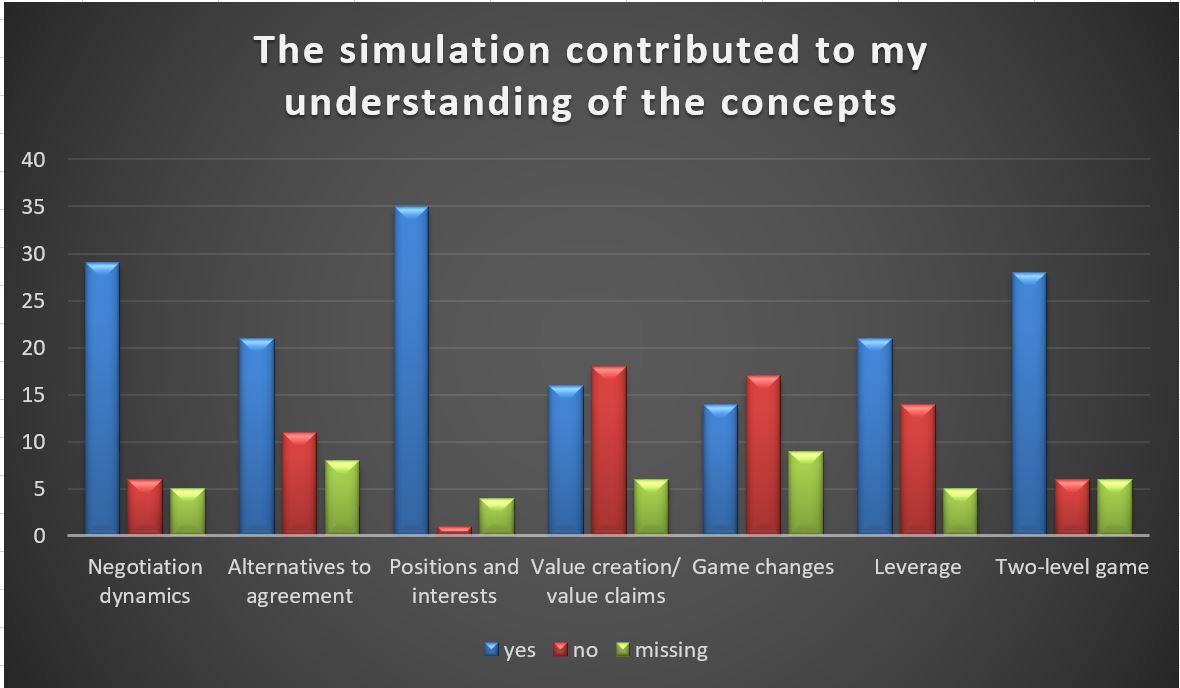

We asked students whether the simulation contributed to their understanding of specific concepts from the assigned readings. Differences regarding which kinds of concepts were perceived to have been understood better may reflect simulation design or individual differences in negotiation approach in the breakout rooms. Two-level games are a good example from our exercise – the integration of Northern Ireland as a player (despite being a part of the United Kingdom) allowed students to experience the challenges of multi-level negotiations rather than staring at a lecture slide with complicated flowcharts.

Elsewhere, in keeping with the trend, concepts that lend themselves to a bargaining approach (e.g. positions and interests rather than value creation) seem to have fared better. Here, the constricted brief (limited to two issues) and the entrenched nature of Brexit negotiations may have led students to overlook the possibilities to change the underlying dynamics or re-frame positions. It is important to note that adapting simulations for online teaching also means considering which (parts of) concepts translate to the online environment. For example, the role of body language is likely to be different in online and face-to-face negotiations. This does not mean that adapting simulations produces a net loss in terms of conceptual learning. In fact, the knowledge and skills acquired in this context may well prove useful in the future, where real-world negotiations are more likely to be conducted online. For instance, multi-channel communication competency i.e. switching between different modes and rules of engagement, strikes us as a crucial skill to be honed even after the pandemic, perhaps in hybrid and blended simulation formats that use face-to-face and online elements.

Finally, even the best-designed open simulation, whether online or offline, will include processes and learning outcomes that do not occur as anticipated by the designer or instructor. Counter-intuitively, rather than being a problem to be solved by providing additional scaffolding, this divergence can fruitfully inform post-simulation discussion. For instance, it can prompt students to compare their different simulation experiences among themselves as well as to the relevant literature. This underlines the necessity of leaving sufficient time for follow-up reflection.

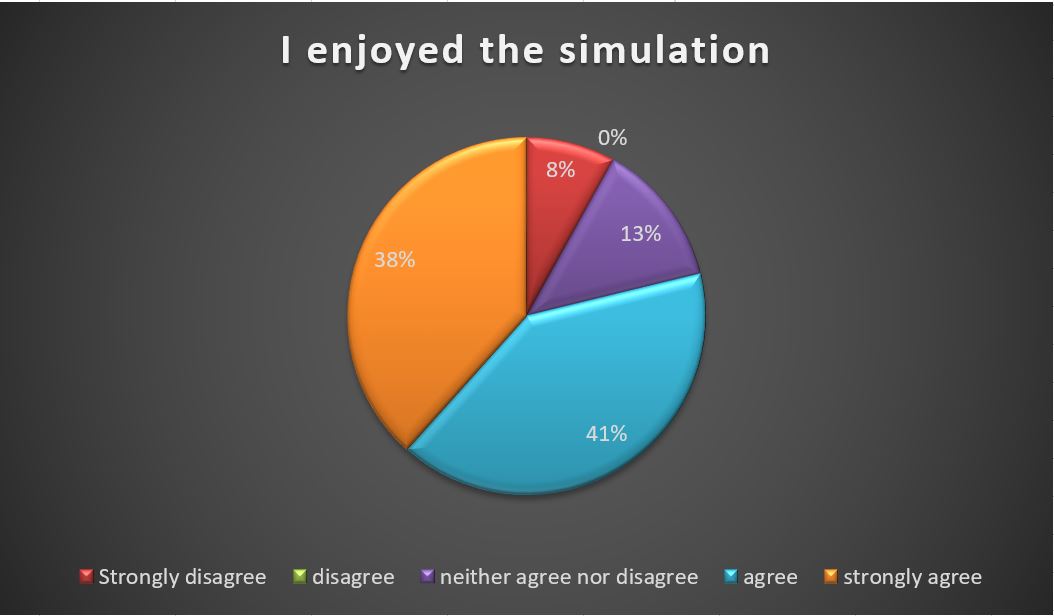

Interestingly, students self-identifying as “usually participating less frequently” indicated that the activity helped them engage and participate more than usual, both in the role-play as well as in the reflection session. One student commented, “Being able to deeply interact […] with fellow students is something that I have really missed [during] this Corona-struck year.” The short activity also retained a key advantage of longer, face-to-face simulations: 78% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they enjoyed the simulation.

Some students suggested that the format should be improved to a larger-scale, more open design akin to the face-to-face simulations they were used to. While in principle this is possible by including off-the-shelf solutions, adapting larger-scale simulation activities to online environments may quickly become overly expensive in terms of technology and time. The necessary balance between intended learning outcomes, student enjoyment, and simulation design in online settings given these constraints will therefore continue to be a challenge for political science teachers. Small-scale simulations can be a suitable first step to (re-)introducing activity-based learning in the virtual political science classroom. For conceptual learning, they need to be combined with clear expectations, asynchronous preparation material, and sufficient time for synchronous and asynchronous reflection. Insights gained may also inform hybrid solutions which reflects of the increasing digitisation of (international) politics.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Image credit: Guido Hofmann on Unsplash