LSE’S early accommodation was modest, writes Sue Donnelly, but it set the model for the School’s location in the heart of London – between the City, government and the law.

From 1895 to 1902 the School was based in the Adelphi, an area between the Strand and the Thames, developed between 1768-1774 by the Adam brothers – John, Robert, James and William. The development included a block of 24 neo-classical houses and a purpose built home for the Royal Society of Arts which moved to the area in 1774.

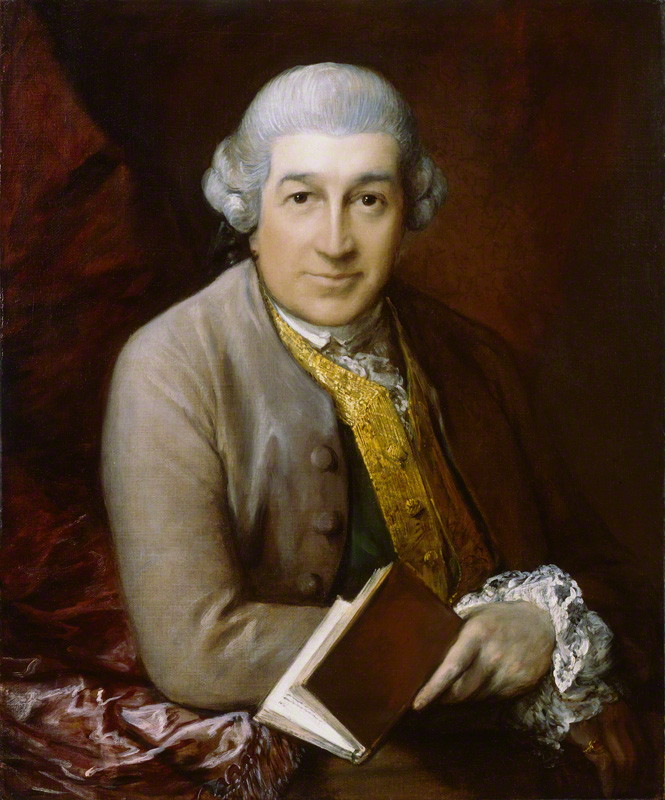

The development was not a financial success for the Adam brothers despite the support of the actor, David Garrick, who lived in one of the houses. By the nineteenth century the development was a mix of domestic houses and offices with Charing Cross station close by.

Initially LSE was housed in three rooms at 9 John Street, now John Adam Street, all sparsely furnished. Director Hewins wrote that students found “an almost unfurnished room where there was a bureau and two chairs, one for myself and on for my visitor”.

Harry Snell, who was appointed secretary, described the rooms as dark and depressing.

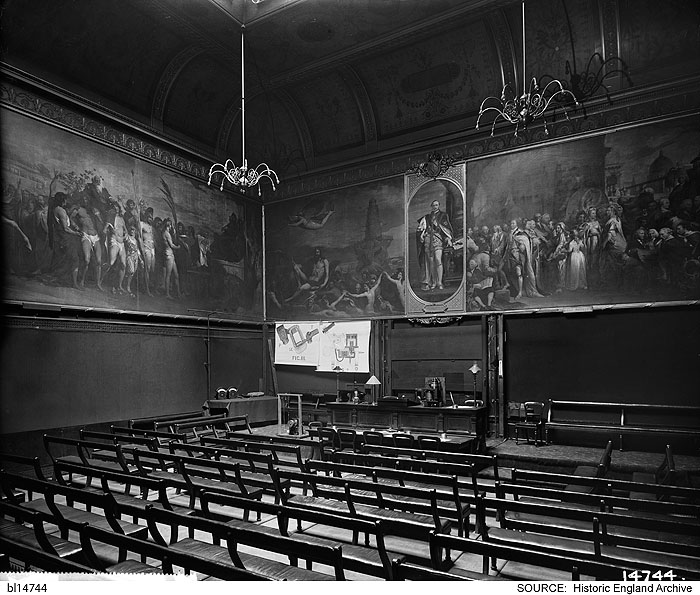

It was clear that the space too small to accommodate the public lectures which were central to the new School’s programme. One obvious solution lay with the School’s neighbour, the Royal Society of Arts. Hewins, wrote to the Royal Society and after convincing them their lecture hall would not be used for political propaganda, secured its use for the School.

Sidney Webb had a solution for the School’s commercial lectures. In 1894-1895 the London Chamber of Commerce ran a series of lectures by Professor William Cunningham aimed at the staff of existing Chamber of Commerce members. Webb spoke to the secretary of the London Chamber of Commerce, Kenric Murray, and persuaded him of the benefits of the School delivering these courses as part of their “Higher Commercial” offerings. Webb estimated the room would seat over a 100 students. He also knew that the support of the Chamber of Commerce would open other sources of funding, notably from London County Council. It was agreed that the School would have use of the room for two evenings at no charge.

Despite the support of the RSA and Chamber of Commerce the School needed better accommodation. In March 1896 Hewins reported to the trustees that following the departure of the Crichton Club, a literary and artistic society, 10 Adelphi Terrace was available. The rent would be £350 per annum for a seven and three quarter year lease beginning on 24 June.

The trustees agreed to the lease and Hewins was given permission to enter into negotiations and get estimates for sanitary alterations and decoration. On 22 June the trustees agreed to let the top two floors to Miss Payne Townshend, later Mrs Shaw, for £150 per annum rent and £150 per annum service charge. Miss Payne Townshend would occupy the top two floors of the house with a dining room and large drawing room on the second floor and bedrooms and a kitchen on the third floor. The third floor would later include George Bernard Shaw’s study but there was no bathroom.

The lease to the house was finally signed on 6 July 1896 and Beatrice Webb and the Director were deputed to find a housekeeper. They appointed Miss Mabel Hood on a salary of £100 per annum. When Miss Hood retired due to ill health she was replaced by Christian Mactaggart who developed the role into that of secretary to the Director and eventually School Secretary.

The good news was that the house had space to accommodate a library, the next part of Sidney Webb’s grand plan for a research institution. Later in 1896 a Miss Appleyard was appointed to catalogue books and Sir Hickman Bacon was persuaded to donate £1,000 for bookcases.

Arthur Sargent, later Professor of Commerce, remembered sitting in lectures and classes held in the basement of 10 Adelphi Terrace. The Library Reading Room was agreed to be fine with a beautiful fireplace and ceiling.

But by 1900 the School had outgrown Adelphi Terrace and was planning its next move to Passmore Edwards Hall and a permanent home on Clare Market and Houghton Street.

This post was published during LSE’s 120th anniversary celebrations