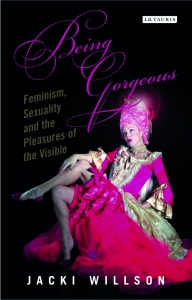

Being Gorgeous: Feminism, Sexuality and the Pleasures of the Visible explores the ways in which ostentation, flamboyance and dressing up can allow women to subvert traditional notions of femininity through ‘pastiche, parody, or pleasure’. Taking examples from ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, Jacki Willson examines how modern-day female performers can establish their own version of femininity through its reappropriation, writes Katherine Williams.

Being Gorgeous: Feminism, Sexuality, and the Pleasures of the Visible. Jacki Willson. I. B. Tauris. 2015.

Being Gorgeous: Feminism, Sexuality and the Pleasures of the Visible by Jacki Willson, Lecturer in Cultural Studies at Central Saint Martins, aims to revise scholarly assumptions regarding ‘visual pleasure, feminised performance, and objectification’. This can be achieved, according to the text, by unpicking contemporary debates surrounding women’s performativity and objectification. The author encourages the reader to see past academic feminists’ theorising regarding the subject/object dichotomy, and to consider what it means for women to be transformed from being merely ‘sex objects’ to ‘self-determined art objects’. If we, in the author’s words, allow ourselves ‘to be pulled into the whirligig of vibrant colour, lip gloss, carousel horses, and false eyelashes, what happens then?’ The author explores such notions of visual pleasure through an examination of photography, performance, art, fashion, cinema, popular culture, cabaret, burlesque and celebrity.

Being Gorgeous: Feminism, Sexuality and the Pleasures of the Visible by Jacki Willson, Lecturer in Cultural Studies at Central Saint Martins, aims to revise scholarly assumptions regarding ‘visual pleasure, feminised performance, and objectification’. This can be achieved, according to the text, by unpicking contemporary debates surrounding women’s performativity and objectification. The author encourages the reader to see past academic feminists’ theorising regarding the subject/object dichotomy, and to consider what it means for women to be transformed from being merely ‘sex objects’ to ‘self-determined art objects’. If we, in the author’s words, allow ourselves ‘to be pulled into the whirligig of vibrant colour, lip gloss, carousel horses, and false eyelashes, what happens then?’ The author explores such notions of visual pleasure through an examination of photography, performance, art, fashion, cinema, popular culture, cabaret, burlesque and celebrity.

The author discusses her appreciation of the film Marie Antoinette (directed by Sofia Coppola, 2006) in the introductory part of her text. The film, states the author, is a breath of fresh air, politics notwithstanding; it is set against a popular culture in which women’s bodies are defined, and subsequently controlled, in a particular way. The women portrayed in Marie Antoinette are performing female experiences by way of ‘an erotic visual surface’. Many women in contemporary society also use a highly visual surface to experiment with a wide range of identities, looks and sensual experiences. The construction of a physical identity, as it were, to promote female empowerment and self-esteem may seem a little at odds with rising feminist mobilisation surrounding issues such as objectification (think Everyday Sexism, iHollaback, No More Page 3 and so on), thus the question is raised: how can ‘being gorgeous’ run parallel to campaigns that aim to challenge society’s typically male ‘gaze’? Could ‘being gorgeous’ mount any positive resistance to the imbalance of gender in society?

The author has raised an important point overall, especially with regards to how experimenting with visual aesthetics can empower women to throw off the tropes imposed by traditional notions of femininity and its associated stereotypes. However, an element I find problematic is her conception of young women who may not buy into the notion of ‘being gorgeous’ as a serious means of resistance against patriarchal societal standards as having ‘antagonistic perceptions’ of feminism. We all dress to impress, and we certainly like to project something of our personality in the clothes we choose to wear; this can be positive or negative depending on how you want to look at it. A question I would like to pose is this: is all this talk of dress-up, cupcakes, lip gloss, wigs and dresses simply another way in which women can be distracted from core issues that directly affect their lives? Marie Antoinette may represent a certain aesthetic narrative that the author finds inspirational, and pivotal to her study of feminism, sexuality and the power of visual pleasure, but the consequences of ignoring political upheaval in revolutionary France had a very real human cost for the actual Marie.

Image Credit: Prerana Jangam (Public Domain Pictures)

Image Credit: Prerana Jangam (Public Domain Pictures)

Being Gorgeous comprises of four principal parts, each with two accompanying chapters. Topics discussed run from sex, pleasure, violence and identity to objectification and objecthood. For the purpose of this review, I will concentrate on Chapter Two, ‘Skin Deep’, to see how the author reconciles with questions surrounding objectification.

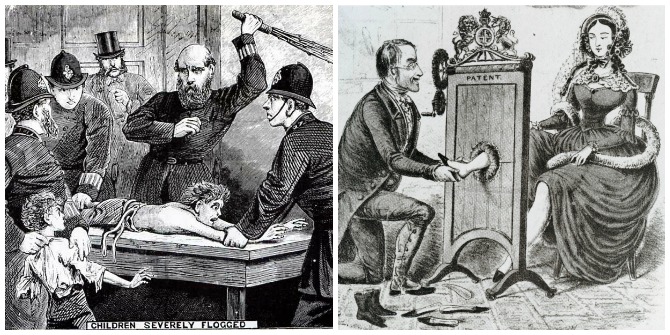

In ‘Skin Deep’, the author reminisces about attending a burlesque event. At ‘Naked Girls Reading’, the atmosphere was ‘friendly, comfortable, and welcoming’, and the attendees pondered amongst themselves what the nakedness would entail. Would the performers be strategically draped with material to cover all the right places, or naked naked? Well, naked naked was the eventual answer, and the attendees enjoyed a liberating evening watching beautiful naked women reading. As Wilson rightly points out, the debate surrounding the objectification of women is often a difficult one to unpack. Whilst the female performers at ‘Naked Girls Reading’ had undoubtedly made a choice to participate in the event and felt comfortable doing so, the naked truth is that the objectification most women experience on a daily basis is not so highbrow or, indeed, liberating. The audience at burlesque events may be predominantly female, but the same unequal power dynamic between audience and spectator exists; women’s bodies are on display for consumption regardless of the gender of the gaze. Why weren’t the audience also naked? The author believes that events such as ‘Naked Girls Reading’ give the audience a chance to see:

‘the woman with all her foibles, personality, and opinions. We get to hear her character, share her literary tastes and choices and story, whether that is her undergraduate years studying sculpture, or her memories of being read ‘‘Snow White and Rose Red’’ as a child. We get to meet the whole person.’

But who exactly qualifies for this feted transformation from sex object to self-determined art object? Is it just beautiful, visually striking women who perform burlesque routines? I suspect that the so-called foibles of performers in ‘Naked Girls Reading’ are not the same ones that spring to mind when we consider our own particular idiosyncrasies. In particular, some class analysis might have helped to make the author’s argument a little clearer. Would we be having the same discussion of visual pleasure if the performers did not meet traditional standards of beauty, hadn’t read the right books or hadn’t been to university?

Being Gorgeous is certainly a thought-provoking read, especially if you are interested in performance art, visual aesthetics, extravagance, costume, cabaret and burlesque. If you are not concerned with these subjects (or even if you are, but have a different opinion on them), you may find yourself getting a little frustrated as I did, especially when trying to unpack the author’s argument surrounding performance and objectification. I feel that something is missing: namely, an in-depth analysis of how activities such as burlesque, cabaret or performance art arguably only seem to be emancipatory for certain groups of women, i.e. those who are middle-class and university-educated. What is liberation for some women is exploitation for others, and that is a conversation definitely worth having.

Katherine Williams graduated from Swansea University in 2011 with a BA in German and Politics, and is currently studying for a MA in International Security and Development. Her academic interests include the de/construction of gender in IR, conflict-driven sexual violence, and memory and reconciliation politics. You can follow her on Twitter @polygluttony.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

2 Comments