Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue is a transcript of a conversation held between US New Atheist, Sam Harris, and Maajid Nawaz, a British Muslim reformer who runs the counter-extremist Quilliam Foundation. While this dialogue provides a nuanced discussion of how to confront Islamic extremism between two scholars approaching the issue from considerably different perspectives, Devan Hawkins questions the emphasis placed on ideological over political motivations.

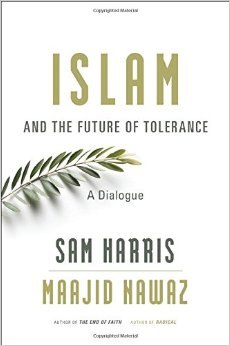

Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue. Sam Harris and Maajid Nawaz. Harvard University Press. 2015.

A mass shooting in California. Attacks in the theatres and cafes of Paris. A bomb in a Russia-bound plane over the Sinai. That all of these events have happened over the past few months and all seemingly originate with the same organisations begs for an explanation. One of the most frequently heard explanations is simple: it is Islam, or, at least, a particularly dangerous interpretation of Islam. ISIS and its affiliates are an Islamic group, comprised of Muslims who profess an Islamist ideology. Therefore, if we want to do something about ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram and all the other Islamist organisations, we must do something about Islam.

A mass shooting in California. Attacks in the theatres and cafes of Paris. A bomb in a Russia-bound plane over the Sinai. That all of these events have happened over the past few months and all seemingly originate with the same organisations begs for an explanation. One of the most frequently heard explanations is simple: it is Islam, or, at least, a particularly dangerous interpretation of Islam. ISIS and its affiliates are an Islamic group, comprised of Muslims who profess an Islamist ideology. Therefore, if we want to do something about ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram and all the other Islamist organisations, we must do something about Islam.

This explanation is not just an academic one. In an October speech, British PM David Cameron laid out his strategy for curbing radicalisation in the UK: ‘What we are fighting, in Islamist extremism, is an ideology.’ In the US Republican Primary, candidate Donald Trump recently supported a ban on Muslims entering the USA, and Ben Carson argued that it would not be appropriate for a Muslim to be President.

The role of religious ideologies throughout history, including those of Islam, is certainly not blameless. In a passage from The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins asks us to imagine a world without religion in which there would be:

no suicide bombers, no 9/11, no 7/7, no Crusades, no witch-hunts, no Gunpowder Plot, no Indian partition, no Israeli/Palestinian wars, no Serb/Croat/Muslim massacres, no persecution of Jews as ‘Christ-killers’, no Northern Ireland ‘troubles’, no ‘honor killings’, no shiny-suited bouffant-haired televangelists fleecing gullible people of their money. Imagine no Taliban to blow up ancient statues, no public beheadings of blasphemers, no flogging of female skin for the crime of showing an inch of it.

All of these certainly have or had religious elements, but can we really say if it were not for religion, they would not have taken place? Equally, even with the obvious religious elements of Jihadist extremism in the world today: is religious ideology the best place to intervene to stop it?

That is the conclusion reached in Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue. This short book is a transcript of a conversation between Sam Harris, a US New Atheist, and Maajid Nawaz, a British Muslim reformer who once was an Islamist, about the dangers of Islamic extremism and how to confront it.

Image Credit: youtube

Image Credit: youtube

It may seem unlikely for these men to be working for the same ends, but, as Harris states early in the book, ‘my primary goal is to support you.’ As a strong critic of Islamic doctrine, Harris may not agree with Nawaz’s claim that ‘Islam is not a religion of war or of peace’, yet he accepts that, as he told Nawaz at their contentious first meeting, it may be useful to pretend this is true.

The book follows from this shared goal to Harris stating his views about why Islam is an impediment to modernity and Nawaz offering ways by which the religion can be reformed so it is no longer an impediment. They sometimes disagree, but the areas where they find most agreement are informative. For example, they both view liberal apologists for Islam, whom they label ‘regressive leftists’, as one of the main obstructions in the fight against radical Islamic ideology. For Harris, one of their main failings has been their insistence that we ‘never take Islamists at their word and that none of their declarations about God, paradise, martyrdom, and the evils of apostasy have anything to do with their real motivations’. For Harris, if we want to understand the motivations of Islamists, we only need to listen to what they say these are, which are almost entirely religious.

But is this true? In October 2004, when a video surfaced showing Osama bin Laden taking responsibility for the 9/11 attacks, he rejected the common claim that the attacks were motivated by hatred of freedom asking: ‘If so, then let him explain to us why we don’t strike for example – Sweden?’ Rather, he states, ‘we fight because we are free men who don’t sleep under oppression. We want to restore freedom to our nation, just as you lay waste to our nation. So shall we lay waste to yours?’ While there are religious aspects to the statement, it largely deals with terrestrial concerns, such as the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, both of which left tens of thousands dead.

None of bin Laden’s words remove his guilt for the deaths he caused—a solely religiously motivated crime is just as heinous as a politically and religiously motivated one. But if one of the cardinal sins of ‘regressive leftists’ is their willful ignorance of the role religion plays in Islamist terrorism, is it not just as wrong to downplay the role that politics play?

Nawaz argues for a more nuanced view, observing that there are four relevant factors for radicalisation: ‘a grievance narrative […] an identitiy crisis; charismatic recruiters; and ideological dogma’. All of these factors are important, but for Nawaz ideology is the central area in which to intervene, stating that ‘the grievances themselves will always be there. It’s the nature of life. What we can change is the ideological lens, or the tribal nature of one’s identity, or the identity–politics games we tend to play’. Nawaz runs the organisation Quilliam, which seeks to counter extremist ideology. This work is important and for Nawaz and others in the Muslim community, countering extremist narratives may be one of the best ways to counter extremism. But for many, especially non-Muslims in the West, changing ideology is a tall order. A more effective strategy may be to stop creating further grievances that contribute to the narrative.

It is clear that ISIS is partly motivated by one of the most violent and regressive interpretations of Islam imaginable. But so are other demagogues and organisations. What is most dangerous about ISIS is their ability to recruit large swerves of the Syrian and Iraqi populations, not to mention many from overseas, to their cause. Most of the forces that made this recruitment possible are political.

A 2015 Guardian article quoted a Jihadist and former prisoner of the US-run Bucca prison facility in Iraq as saying: ‘If there was no American prison in Iraq, there would be no IS now. Bucca was a factory. It made us all. It built our ideology.’ This is not to say that these prisons created the ideology. For instance, while Al-Baghdadi, ISIS’s leader, recruited many of the earliest members from Bucca, there are reports that he supported an Islamic revolution against Saddam Hussein long before the 2003 invasion of Iraq. But is it not reasonable to suggest that if the US invasion had not taken place, it would have been much more difficult to find recruits for ISIS? Not invading a country, or not supporting Middle Eastern despots or not backing the occupation of another people’s land, are all much easier prospects for US foreign policy than altering individual ideologies.

None of these facts should discount the importance of fighting radical ideologies. These issues are complicated and require multiple fronts to find a solution, but I fear the conversation in the West has concentrated too much on Islamist ideology. This focus has often had the effect of demonising Muslims. It is important that people like Nawaz fight radicalisation in Muslim communities and I hope that his conversation with Harris in Islam and the Future of Tolerance will help in that mission. At the same time, it is important that these conversations do not play down the role of other factors beyond ideology in the rise in extremism, because those may be the most effective areas in which to intervene.

Devan Hawkins is a freelance writer from Massachusetts. He has had writing published in the Islamic Monthly, Antipode and Radical Philosophy.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

2 Comments