In 1917: War, Peace and Revolution, David Stevenson offers a detailed and well-structured narrative of the complex, interlocking events of this fateful year, with an eye to their subsequent impact on the unfolding twentieth century. Stevenson’s masterful account should be essential reading for anyone with a particular interest in the First World War, recommends Benjamin Law.

1917: War, Peace, Revolution. David Stevenson. Oxford University Press. 2017.

Last year saw many anniversaries: of the Reformation, of the publication of Karl Marx´s Capital and, perhaps the most significant, of the Russian Revolution. The centennial of the latter brought with it the publication of a long list of books narrating the events of October 1917. China Miéville, Tariq Ali and Slavoj Žižek in particular came to the forefront due to their insistence that we can still learn from the achievements and mistakes of that autumn.

Yet 1917 was a year which is also significant because of other events that cast the modern world in their mould. For instance, the modern Middle East, the eventual independence of India and America’s rise to global dominance were born out of the blood and fire of the First World War and, in particular, the events of 1917.

It is this year that David Stevenson, Professor of International History at LSE, investigates with his detailed new account, 1917: War, Peace and Revolution. In four large but not overwhelming sections, Stevenson takes the reader through the events of the year, with an eye on how they also help us to understand the path of the century that followed. If World War One was a dress rehearsal for anything, then it was for a large part of the subsequent history of the twentieth century.

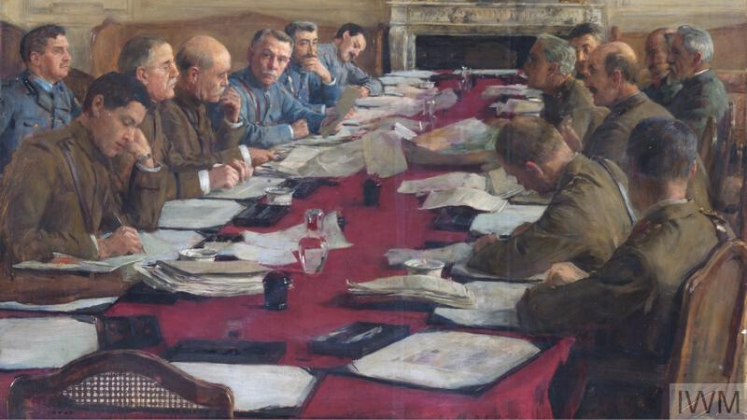

Stevenson shows the complexity that confounded the protagonists in 1917, from princes to revolutionaries, generals to viceroys. From the fraught debates over America’s entry into the war to the tense strategising over the Passchendaele Offensive, Stevenson gives us an in-depth and well-structured narrative that leaves the reader with a greater understanding of each of the events. Though he goes into the minute detail of all the conferences, peace deals and declarations, one never loses sight of the fact that, despite the politicking, this is a story about conflict, revolution and numerous failed attempts at peace.

The most striking thing that comes out of the book is that we can so easily imagine how history might have been different had the major figures of the time come to their senses and ended the conflict. This eventuality was not all that remote. Stevenson’s chapter on the peace overtures between the Allies and the Central Powers is a case in point. His scholarly and forensic detailing of Prince Sixte de Bourbon’s (brother-in-law to the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne) prolonged attempt at securing a peaceful solution by using his family connections to the new Austrian emperor and by offering concessions and territorial trade-offs may give the reader a pang in the stomach at the stubbornness of the heads of government which prevented any early truce being declared. Stevenson also convincingly portrays the last efforts of the transnational aristocratic elite that had dominated the preceding century. We know that all these Hapsburgs, Romanovs and Hohenzollerns are doomed, but in Stevenson´s account they are allowed to waltz their last in the ballroom of history – albeit under the critical gaze of the historian.

As Stevenson reminds us, Sixte was just as disingenuous to the negotiators of the failed peace talks as he is to us through his private recollections. In the end, we are left wondering about the commitment and capability of the negotiators on both the Allied and Central Powers’ sides with regards to securing peace. As Stevenson himself writes:

The breakdown of the 1917 peace feelers can be explained at different levels. Certainly it demonstrated the perils of amateur diplomacy. An older Catholic, aristocratic, and dynastic Europe, alongside the socialists and portions of the business elite, attempted to transcend divisions, as later it would support continental unification.

In short and in the face of the coming social upheavals in Russia, Germany and the ramshackle Hapsburg Empire, the old European establishment simply no longer had the clout to influence history.

Considering that the 1914-18 conflict was a ‘World War’, it is welcome that Stevenson dedicates a chapter to the non-European belligerents. He shows the back-and-forth nature of the debates in countries such as Brazil and Siam about entering the war, and thereby convincingly demonstrates how the tangled tentacles of the conflict spread out across the Pacific and South East Atlantic. Thus one can truly understand the global repercussions of the conflict.

One of these was the loosening of European colonial rule in Asia. As Stevenson argues, white imperialism was beginning to weaken there, and the process which led to independence throughout Asia was accelerated by the First World War. Stevenson´s chapter on the beginnings of ‘responsible government’ for India, which led to eventual independence, is a good example. The impact of the war on British rule and the decision to give the subcontinent self-rule, albeit to a very limited degree, is made quite clear. ‘It meant the dismantling of the British Empire’, writes Stevenson, ‘of which it was the precedent and of which the war was itself the precedent’. The increasing financial burden on running the Raj, and in particular the Royal Indian Army, meant that while the British Raj could pack a punch as far afield as the Middle East and the Western Front, it came at an ever-higher financial cost, borne mostly by the Indian population themselves.

Stevenson is right to argue that the war helped to push the situation in India from negotiations driven by peaceful top-down politics towards a more direct call for home rule. Here, it would have been useful to explore the deeper grassroots of nationalism to shift the focus away from the British rulers, which would give the reader a greater sense of how much of a change 1917 precipitated. As it is, Stevenson is too keen to portray the beginning of the end of British rule as a result of a prudent realisation on behalf of the British that India was ready for self-rule rather than being forced by protest into imperial retreat. In fact, and there is little mention of it in 1917, the British came under pressure from Indians themselves, and it would have been to Stevenson’s credit had he made further space for an Indian perspective in the story. Nevertheless, the sense of history is evident in Stevenson´s acknowledgement that the Montagu Declaration of 1917 ‘remains the starting indicator for processes that led to independence not only for India but also for the rest of the British Empire, and even for the Western colonial empires as a whole’.

In essence, 1917 was a year of failures. Stevenson ends his account with a harrowing yet powerful portrait of the decaying international order that caused them. Even as the ‘great men’ of the period negotiated in ‘metropolies and in Rhineland spas, in country houses and in railway carriages’ and took to ‘repairing after their deliberations to brandy and schnapps’, Stevenson reminds us that, at the same time, they were simply a group of ‘old men consigning young men to oblivion’. It is all the more shocking that they seemed happy to leave it that way. For the leaders of the conflict, the mass slaughter from Flanders to Mesopotamia had become something to which they were accustomed. As a result, these old men were not resolved to ‘terminating the conflict’, but simply to heading for the most convenient exit.

The events of 1917 have left their mark on the present world. Given the literature that has been written on the anniversaries of such events as the October Revolution, the Balfour Declaration or the Armistace of 1918, one could feel spoilt for choice about what to read on this topic. Stevenson’s masterful account of the fateful year should be essential reading for anyone with a particular interest in the First World War or the opening years of what is typically considered the bloodiest century in human history. Stevenson’s 1917 is also a good example of why it is advantageous to go back to past events and dates, dust them off and read about them anew.

Benjamin Law studied both in the UK and Germany and holds a BA in Philosophy and History and an MA in History. In the past few years he has worked for an NGO, supporting the German education sector. Additionally, he has worked as an editor and translator on an array of academic texts and journals. He currently lives in the UK where he continues to work in the education sector.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Soldiers of Australian 4th Division field artillery brigade, Chateau Wood, near Hooge in the Ypres salient, 29 October 1917 (Australian War Memorial collection number E01220: CCO Public Domain).

Find this book:

Find this book:

2 Comments