In this feature essay, The Case of Brexit, Expertise and Linguaphobia: Cosmopolitanism, Language and the Politics of Value, Sarah Burton argues that the heightened expression of antipathy towards languages other than English in the post-Brexit context denotes a form of ‘othering’ that is intertwined with concurrent anxieties regarding expertise, cosmopolitanism and intellectualism in the contemporary moment.

This essay is part of the LSE RB Translation and Multilingualism Week, running between 10 and 14 December 2018. If you are interested in this topic, all posts published as part of the week can be accessed here. If you would like to contribute on this topic in the future, please contact us at Lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

‘You need to speak English, you’re in fucking England’

– reportedly said during an attack on a Spanish-speaking woman on a London Overground train, October 2018

‘I think the people of this country have had enough of experts’

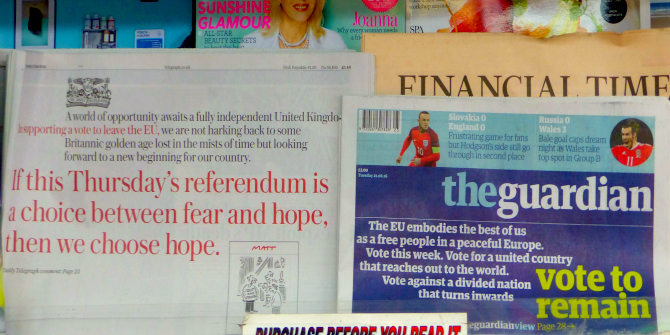

Post-Brexit Britain is febrile – racially and xenophobically charged to an extent where the Home Office admitted a one-third rise in hate crimes following the EU referendum, scholars of race and racism declare ‘a state of emergency’, and the day before the referendum MP Jo Cox was murdered by a man allegedly using the words, ‘Britain first, this is for Britain, Britain will always come first’. Research has shown that anti-intellectualism – the rejection of experts and expertise – is linked with voters’ support for movements that share this standpoint, such as the Vote Leave campaign, Jair Bolsonaro’s presidential victory in Brazil and Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’. These movements tend to sway to the (far) right of the political spectrum and, concomitantly, researchers have noted a substantial mainstreaming of far-right politics. These groups and campaigns position themselves as openly hostile to ‘identity politics’ and secure their rhetoric in romanticised versions of the past (Virdee and McGeever 2017). In the case of Britain, these narrate the country as homogenously white, whilst expressing a melancholia for an apparently lost English idyll (Saha and Watson 2014), particularly around the decline of imperialism and empire.

But how exactly does a rise in racism and xenophobia segue with a rejection of experts and intellectuals – and, pertinently, how can we understand this denunciation of expertise more particularly by focusing on language and linguaphobia? What might an orientation to the politics of language draw out in terms of value systems that have public appeal and the ways that narrations of culture, cosmopolitanism, elitism and modernity are pulled through both anti-intellectual as well as racist and xenophobic views and actions? This short piece draws out the relationship between linguaphobia, racism and cultural capital to pose questions related to the problem of the intellectual or expert’s perceived elitism and disconnection from people’s everyday lives and concerns.

Linguaphobia and racism: borders, boundaries and belonging

A common element of rising hate crime and increased experiences of racism and xenophobia in post-Brexit Britain are attacks seemingly motivated by victims speaking languages other than English. A clear element of this violence is the identification by the perpetrators that the language people use marks them out as belonging in the UK – or not. So what is it about language – particularly the way that English and English speakers relate to other global languages – that means it becomes aligned with forms of racist border control? And, importantly, how does this rejection of languages other than English in the UK help us to better comprehend the rejection of the expert or intellectual? What is significant to each is the way that both are seen as foreign, suspicious, out of touch and therefore an apparently legitimate object of attack in a country suffused by the rhetoric of ‘taking back control’ from vaguely-identified and nebulous external powers.

There are multiple forms of linguaphobia – both that speaking a language other than English in public risks a racially-aggravated attack, but also a broader hardening of monolingual attitudes from English speakers. Research has shown that, post-Brexit, a third of state schools reported that leaving the EU has had a negative impact on both student motivation to learn languages other than English as well as on parental attitudes to language learning. Moreover, there is a widespread – though erroneous – assumption that English is the lingua franca of the world. The attitudes and assumptions which underpin both forms of linguaphobia are arguably tied to pervasively-sold cultural memories of Britain as a country of empire and expansion, wherein these forms of colonisation and domination are understood as not only acceptable but desirable. In this sense, the speaking of English functions both as a form of border control – the acceptable and legitimate language of the space of Britain – but also as a performance and assurance of patriotic loyalty. Under these conditions, languages other than English and the people who speak them are regarded with suspicion and positioned both as ‘other’ and dangerously ‘foreign’. The hardening of these conceptual and imaginative state boundaries is mirrored, and amplified, through the very literal hardening of state boundaries and deliberate creation of a ‘hostile environment’ carried out through the border control policies of the Home Office – and the treatment of the Windrush generation is a key example of this.

The paradox of language and expertise: problems of inclusion and exclusion

Given that language represents not only geographical location or origin but also modes of communication, understanding, interpretation and feeling, as a phenomenon it is connected not simply to nationality and statehood but also, crucially, to ideas of knowledge and knowing (Susen 2018). Despite commentators claiming language as a straightforward, easily translatable tool which offers no insight into the peculiarities and idiosyncrasies of culture or society, research in linguistics instead demonstrates that there is a level of incommensurability and particularity to languages, which holds rich interpretive functions. Thus an understanding of multiple languages – especially in how each works to describe and structure the world – aids us in comprehending and articulating the contradictions, nuances and paradoxes of experience and knowledge. Significantly, a number of racist attacks on people for not speaking English have been claimed to result from perpetrators feeling ‘paranoid’ about what might be being said that they cannot understand. As such, shared languages function as interpretive avenues, but a lack of common linguistic horizon equally works as a barrier not just to communication but also to conviviality of citizenship and belonging. This is, of course, not to reduce the culpability of racist actions, but to begin to draw a relationship between fear of ‘the other’ and processes of othering themselves.

Moving towards connecting this linguaphobia with the rejection and vilification of experts and expertise, it is necessary to consider the relationship between language and cultural capital. This emerges in two distinct, but linked, ways: firstly, in a more literal sense which pivots on the conventional and stereotypical depictions of intellectuals as connected to ideals of Enlightenment Europe – including linguistic dexterity, travel and mobility; secondly, in the relationship between linguistic fluency and forms of privilege and elitism. To be linguistically sophisticated – even in only one language – is to have admittance to forms of interpretation and gaining of knowledge which are not widely or readily accessible to others. As Henry Barnard argues, language and the ability to use it well may give the impression of ‘being purely scholastic and meritocratic, but in reality it is a process for ensuring that those born privileged are twice-born’ (1999: 139). Part of what allows experts and intellectuals to position themselves as such is their ability to adeptly express themselves – and, on (sometimes frequent) occasion, there forms a language of expertise and intellectualism predicated on jargon and unintelligibility to wider audiences (Bauman 2011; Giddens 1995). Owing to this, the hierarchical positioning of the expert or intellectual is founded on value paradigms that privilege particular forms of knowledge, interpretation and expression, and in doing so, result in prestige and status being afforded to certain individuals who are able to perform within these paradigms. The modes of othering that emerge from the relationship between the expert or intellectual and language are therefore fuelled by complex and enmeshed notions of foreign versus belonging, cosmopolitanism versus domesticity and elitism versus transparency.

The mobile multilingual intellectual: class, cosmopolitanism and modernity

Zygmunt Bauman (1998) suggests two definitive types of mobility in contemporary society: the tourist and the vagabond. The vagabond is involuntarily mobile – at the mercy of violence, war, poverty and urban change. The tourist, by contrast, represents privileged mobility – moving by choice, the business person or traveller who crosses the globe with spontaneity, alacrity and ease. These social types are both racialised and classed – to fit into the category of tourist, it is typically necessary to possess the cultural capital of whiteness and the economic capital of wealth and material resources. The expert or intellectual, with their associated prestige of Enlightenment values of modernity, cosmopolitanism and sophistication, segues clearly with the category of tourist. Intellectuals are not bounded in one particular physical or psychical geography, but rather are often understood as polymaths capable of deftness and suave across multiple spheres.

Under these conditions the dislocation of the expert from a core state territory positions them as a ‘dangerous other’ – and is conceptually analogous with the xenophobia and racism directed towards those who are positioned as outside of belonging because of their language use. That both the intellectual and the speaking of languages other than English involve perceived levels of ‘unintelligibility’ entwine them within forms of elitism – especially in terms of refusing to ‘assimilate’ into homogeneity – and as threatening and troublesomely unknowable. These epithets are underscored by their alignment with representations of the EU by the Vote Leave campaign as undemocratic and opaque. The ‘take back control’ slogan used throughout the Brexit referendum by Vote Leave, in conjunction with the constant denunciation of expertise, further subtly positioned experts and expertise as aligned with bullying and menacing elite foreign powers. Within this context, then, the xenophobic and racist demand that ‘you need to speak English, you’re in fucking England’ can be read both as an invocation of hard borders and a hostile environment as well as a ultimatum for a sort of flat intelligibility that absents nuance, diversity and texture in favour of the homogeneity of a dominant culture.

Nevertheless, within these worrying issues of territorial policing, anti-intellectualism and the connected normalisation of far-right views, there is the more knotty problem of elitism and social class. The rejection of experts and expertise is also a tacit pushback at forms of hierarchical knowledge. Crucially, though, those involved in the Vote Leave campaign – Gove, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage – have all held various elite positions, including Oxbridge educations and careers in the City. The rejection of expertise and intellectuals is not a wholesale recognition and denunciation of elite power but rather a sleight of hand intended to prop up just such a power whilst pretending not to. The murky ambiguities waded into through Brexit rhetoric around experts, and the deliberate creation by the UK Home Office of a hostile environment for migrants, create tinderbox conditions for the production and sharing of knowledge – where to know stuff is seen as dangerous and to be able to express yourself in a way not readily understandable to a wider population is viewed as threatening.

These feverish conditions compel us to ask bigger questions around value – who and what do we value, and what does this say about us as a society? The Leverhulme Trust-funded project I’m currently undertaking approaches these questions from creative and critical perspectives: how can we better understand the role of the intellectual and expert in academia, popular culture, politics and the media by thinking more closely about language, multilingualism and associated epithets of ethnicity, race and cosmopolitanism? Can forms of elitism actually be useful, and how do we tell the difference between exclusionary and inclusionary knowledges? How might we reconfigure the terms of our imaginations, horizons and conceptions of knowledge, interpretation and expression as we begin the very literal process of reconfiguring our borders? And how, in a global political economy predicated on information and communication, can the UK be a part of this without attentiveness to both language and expertise?

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image One Credit: (Alex LA CC BY SA 2.0).

Image Two Credit: (Pixabay CC0).

1 Comments