The edited collection Gender and Queer Perspectives on Brexit brings together contributors to explore the often underemphasised gendered and queer dimensions of Brexit and its potential impact on women and queer communities in the UK and Europe. In this author interview, we speak to editors Moira Dustin, Nuno Ferreira and Susan Millns about the volume.

This interview is published as part of a theme week focusing on LGBT+ scholarship following #IDAHOBIT2019. You can explore more of the week’s content here.

Q&A with Moira Dustin, Nuno Ferreira and Susan Millns on Gender and Queer Perspectives on Brexit (Palgrave, 2019)

Q: What prompted you to bring contributors together to specifically explore gender and queer perspectives on Brexit in your edited collection?

Q: What prompted you to bring contributors together to specifically explore gender and queer perspectives on Brexit in your edited collection?

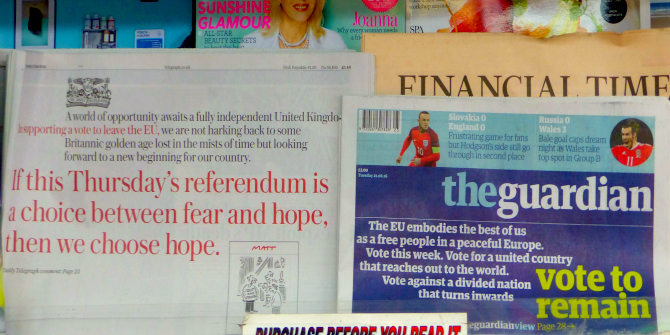

Susan Millns: When a majority of the people of the UK voted on 23 June 2016 in the Brexit referendum in favour of leaving the European Union, this had profound consequences for all European citizens. A huge public debate about Brexit, both before and after the vote, has taken (and continues to take) place, and yet it became apparent to us, the editors of the collection, that the debate has been heavily dominated by certain voices and certain perspectives. Heavyweight, male politicians have taken to the stage and the national conversation has swirled persistently around trade, migration and money using the fighting talk of ‘deal or no deal’.

We took the view that there were (and still are) voices that are eerily silent and perspectives that are clearly missing from the public debate on Brexit. Evidently, some citizens will meet the challenges that lie ahead with resilience and will take full advantage of the opportunities that a return of national sovereignty and a new form of politics promise. However, other citizens will be less fortunate and will see the rights and protections offered by the EU starkly withdrawn, leaving them more vulnerable and with diminished horizons and fewer prospects than previously.

We, therefore, sought to bring together contributors to our collection who would examine the opportunities and challenges, the rights and wrongs and the prospects and risks of the Brexit debate from a particular perspective – that of gender and sexuality. While much was being written about Brexit from legal, political, social and economic perspectives, there was noticeably little debate about Brexit from a gendered and queer point of view, and little analysis of the effects of Brexit on women and gender/sexual minorities who have historically been more marginalised and whose voices have tended to be less audible in political debates – both nationally and at the European level.

The contributors were encouraged to explore how Brexit might change the equality, human rights and social justice landscape, but from the viewpoint of women and gender/sexual minorities, and to think through the impact of Brexit upon women and gender/sexual minorities in a variety of ways, highlighting where contributors thought the particular challenges for these groups might lie. These reveal complex gender dimensions across the spectrum of the Brexit process and outcomes, leading to a consideration of a huge range of issues, including the language and discourse of the Brexit campaign, the voting patterns of men and women, the impact on party politics and for female politicians, together with a myriad of policy questions that are highly important to women and gender/sexual minorities – employment, discrimination, the environment, the single market, free movement, migration and citizenship rights, to name but a few.

In essence, the core of our concern, and the reason why we brought together the group of scholars and activists to work on the collection, was to expose the barely recognised gendered dimensions of Brexit, and to explore the risks and opportunities of the UK leaving the EU for women and sexual minorities both in the UK itself and across Europe.

Q: The chapters on queer perspectives on Brexit focus particularly on the concern that leaving the EU will have a detrimental impact on LGBTQI+ rights. However, the ‘Queering Brexit’ chapter notes that while the EU has been ‘a catalyst’ for an equality agenda encompassing greater LGBTQI+ rights (253), at times UK law has gone beyond EU directives. What perspective do you have on the threat to LGBTQI+ rights as a result of Brexit? Should we be concerned if UK and EU law are no longer working in tandem when it comes to LGBTQI+ equality?

Nuno Ferreira: Our clear message in the ‘Queering Brexit’ chapter is that everyone will have something to lose in the field of gender and sexual freedom and rights – both the UK and the rest of the EU. Although it is true that on occasions UK legislation has gone beyond EU requirements (as is clearly the case with the current Equality Act 2010), it is also true that the EU has been the true catalyst for the dramatic changes in UK equality legislation since the early 2000s. The most obvious example is the Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003, which would probably have taken many more years to come into existence without EU developments.

On the other hand, it is also true that the UK has become a fairly progressive EU member state in relation to equality matters, supporting, for example, the proposed horizontal equality directive implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation, beyond the field of employment. This support has helped keep this proposal on the table, whilst other EU member states have tried to create obstacles to it at every possible opportunity. So, in short, LGBTQI+ rights risk losing support and momentum in both the UK and in the EU if and when Brexit takes place, which will require renewed energy and resilience from sexual and gender minorities.

Q: As the collection acknowledges, there was an LGBTQI+ lobby that campaigned for ‘Leave’ due to the belief that the UK has at times shown a more progressive stance to LGBTQI+ rights than other EU member states. However, it is acknowledged that this perspective can take the form of ‘an inversion of homonationalism’ (251) – could you explain what this is, and how this operates in relation to some perceptions of the EU?

Moira Dustin: Homonationalism is the phenomenon of deploying LGBTQI+ rights to promote a neo-colonial or neoliberal, overly simplistic ‘West-is-best’ agenda. The assumption that Western European liberal democracies are in the vanguard of gay rights enables condemnation of non-European and generally Muslim countries and cultures. In our ‘Queering Brexit’ chapter, we identified an ‘inversion of homonationalism’ in the claims of an LGBTQI+ pro-Brexit lobby that it is the UK and not the EU that truly champions gay rights.

Perhaps this is less an inversion of homonationalism than a new expression of Francesca Romana Ammaturo’s ‘pink agenda’. She coined this term to describe how the promotion of LGBTQI+ identities and claims serves to reinforce distinctions not only between European and non-European states, but also between tolerant and intolerant countries within EU borders. With Brexit we see the battle lines redrawn: in this new homonationalist narrative, the UK replaces the EU as the saviour of sexual and gender minorities, because EU multiculturalism and human rights have opened the door to homophobic and transphobic minorities. As Boris Johnson claimed in March 2016: ‘It was us, the British people, that created that environment of happiness and contentment for LGBT people and it is absolutely vital we fight for those rights today because they are under threat in Poland, in Hungary, in Romania and other parts of the EU where they are not protected in the way they are in our country.’

As with the ‘Saving brown women’ trope identified by Gayatri Spivak a generation earlier, the recognition that liberation agendas can be used consciously or unconsciously to pursue ends that undermine the rights of disenfranchised people – whether women or sexual minorities – creates dilemmas for activists and a need for caution when forming alliances as well as a readiness to interrogate the agendas underpinning ostensibly feminist and LGBTQI+ rhetoric.

Q: What is underscored within the collection is that discussions of Brexit and LGBTQI+ rights can be simplistic if they do not acknowledge that rights vary across the nations of the UK. How important is it to bring a regional perspective when considering the impact of Brexit on LGBTQI+ individuals?

Moira Dustin: We consider it very important to bring both a four-nations and a regional perspective to this discussion. LGBTQI+ people have different experiences and needs depending on where they live in the UK.

The most obvious example of disparity may be same-sex marriage, which is still not legal in Northern Ireland in contrast to the rest of the UK. While the EU may not have been the direct cause of the equalisation of marriage legislation, we argue in our ‘Queering Brexit’ chapter that EU directives were an important driver of equality improvements across the UK, leading to a greater recognition of the need for parity of protection – regardless of location. Equal marriage is an ongoing struggle and while membership of the EU doesn’t require the UK to provide equal entitlement to same-sex marriage, the European Court of Justice may at least ensure residency rights on an equal basis to those denied the right to marry.

Recognising that much progress on LGBTQI+ rights is community-driven and takes place at local or regional level, EU resources can often be valuable enablers of progress, whether in the form of funding streams, guidance and dissemination of good practice, or in facilitating networking between civil society organisations in different member states. In short, the EU provides many tools that – alongside other statutory and NGO resources of one kind or another – enable regional and community activists and service providers to hold national governments accountable. We fear that while these will survive in the short term, they are likely to dry up over time if they are not underpinned by formal UK membership of the EU.

Q: The collection makes clear that exploring queer perspectives on Brexit does not only mean considering the impact of the UK leaving the EU upon LGBTQI+ individuals within the UK, but also upon people across the EU. Do you think more research on Brexit needs to consider these dual impacts, rather than focus on the consequences solely for the UK?

Nuno Ferreira: Although it is people in the UK who will be most harmed by Brexit, people elsewhere in the EU will also inevitably suffer negative consequences in some respects. The UK has become a haven of sorts for gender and sexual minorities across the EU who wish and are able to migrate and find more welcoming and supporting environments in the UK. By seeing their freedom of movement to the UK restricted, these minorities will definitively lose one of the alternatives they currently have to address their needs and vindicate their rights. Those UK citizens wishing to travel, study and work in the EU – amongst whom there will be many LGBTQI+ individuals – will also see their freedoms and rights severely curtailed. Legal recognition and protection of UK-EU27 LGBTQI+ couples will miss out on the substantial arsenal of EU law and mechanisms that have developed over decades. All these risks and areas of potential impact need to be carefully considered and researched from various disciplinary angles during years to come.

Q: Although fewer chapters in the collection focus specifically on queer perspectives on Brexit, many of the issues discussed in other essays have cross-cutting implications (such as disability, asylum law and the impact of Brexit on BME women), showing the importance of looking at ‘minorities within minorities’ (472), as you put it in the conclusion. How crucial is it to adopt an intersectional approach to Brexit, especially when exploring gender and queer perspectives?

Nuno Ferreira: An intersectional approach to analysing and researching the impact of Brexit from gender and queer perspectives is essential. In fact, such an intersectional approach should be the default approach to considering the potential impact of Brexit on anyone and in any field. No single person is uni-dimensional – we all have a range of characteristics that make us both more vulnerable and more resistant to certain external events. Our age, gender, sexuality, ethnic origin, educational achievement, socio-economic status, religious or philosophical beliefs, to name just a few, are markers that influence indelibly how we deal with legal and policy developments and how law and policy are negotiated and agreed. This is no less true for women and LGBTQI+ individuals, who, besides a certain gender or sexuality, have a range of other characteristics that set them apart. It is crucial that we never lose sight of the fact that no group is homogenous and that individuals are extremely complex and unique amalgams of characteristics. An intersectional mindset is thus essential when researching the impact of Brexit on people.

Q: Across the collection, contributors warn against exploring the potential consequences of Brexit solely through the framework of ‘hard’ legislative questions, highlighting some of the ‘soft’ frameworks through which LGBTQI+ rights have been secured and monitored. Peter Dunne, for instance, cites the importance of survey data provided by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) for gaining insight into queer lives across the EU (292). As researchers, do you see leaving the EU as potentially impacting LGBTQI+-related research?

Nuno Ferreira: This is certainly a matter of great concern to researchers in the UK. The UK government has committed to honour the EU research funding that has already been granted by the date Brexit takes place. However, the Draft Withdrawal Agreement does not include membership of the European Research Area (ERA). Although there has been discussion of the UK becoming an associated member of the ERA in a post-Brexit scenario, it is worrying that the UK is even considering abandoning a mechanism that has benefited it more than any other EU member state. The UK is still an official member of the ERA, the official guidance reiterates that UK-based applicants are still welcome to apply and EU research funding is still being granted to UK institutions. Yet, it is clear that many institutions in other EU member states are already avoiding having UK partners in consortiums and joint research projects, and where UK partners are included, they are no longer the project leaders or responsible for significant work packages or key tasks. The ‘brain drainage’ of European academics has also been widely reported, with UK universities losing important knowledge and skills. All these factors combined are bound to leave UK research worse off: with fewer resources, less attractive and less innovative. This will also affect LGBTQI+-related research, which depends to a large extent on radically new thinking, substantial resources for empirical work and a stimulating environment that welcomes, nurtures and respects diversity and cosmopolitanism.

Q: You close the collection by writing that the aim of the volume is not simply ‘the defensive demand for no regression on rights, but also the inclusive aspiration for an expanding rather than narrowing of horizons’ (472). Do you feel hopeful that, regardless of the precise outcome of the ongoing Brexit negotiations, there is the capacity to aim for and forge such expanding horizons for LGBTQI+ rights, both within the UK and the EU?

Moira Dustin: Writing at this moment in time with both the timing and the fact of the UK’s departure from the EU uncertain, this is a difficult question to answer. In our book’s conclusion we suggested that the ‘Overton window’ of discourse, policy and political possibilities was likely to shrink after Brexit. At the time of the book’s publication, a more defined Brexit seemed more likely than has happened so far. The danger now appears to be that the lengthy process of Brexit – which at the time of writing has no end point – consumes all the political energy, resources and creativity needed to make progress on LGBTQI+ and gender rights (as well as progress in any other area of policy and law).

If there is a more positive direction to take in promoting sexual and gender equality and any potential for expanding horizons, perhaps it will come through more alliances and partnerships between LGBTQI+ allies at local, regional, European and international level and a multiplicity of engagement that bypasses national government and introspective politics. Equally, the Brexit debate, for all its flaws, has fostered a level of interest in politics which has been unseen in the UK for decades and has ignited the passions particularly of a younger generation who are living in a new digital age and with new horizons. It is to this political generation, with their creative approaches to connectivity, fluidity and global outreach, that we might look in the future for a more worldly, connected and expansive view of LGBTQI+ rights.

This interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.

Note: This interview gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image One Credit: Photograph taken during the Marche des Fiertés LGBT de Paris (Paris Gay Pride), 2 July 2016 (CCO).

Image Two Credit: London Pride 2017 (MangakaMaiden Photography CC BY 2.0).

3 Comments