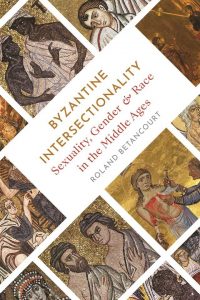

In Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender and Race in the Middle Ages, Roland Betancourt offers a new study that challenges the way that scholars have historically viewed Byzantine society and culture, using the methodology of intersectionality to uncover marginalised identities and recover medieval conversations around sexual and reproductive consent, sexual shaming and bullying, sexual attraction and desire, trans and nonbinary gender identities and the depiction of racialised minorities. This is an exciting and radical new project with an ethical dimension and urgency, writes Meaghan Allen, that seeks to illuminate forgotten figures and lived experiences that ripple through into our present moment.

Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender and Race in the Middle Ages. Roland Betancourt. Princeton University Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Art historian Professor Roland Betancourt’s Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender, and Race in the Middle Ages is an insightful and powerful new addition to not only Medieval Studies, but also History of Art, Critical Race Studies, Gender and Sexuality Studies and Queer Studies. Betancourt’s interdisciplinary approach introduces an impressive range of scholastic materials, ranging from medical treatises to hagiographic texts to contemporary queer theory. Part of what makes Betancourt’s endeavour so successful is the accessibility of his writing to academics and non-academics alike. Furthermore, the use of thematic section headings allows for smooth navigation through the text’s five main chapters, encouraging the reader to return to previous sections without fear of losing one’s place. An exciting and radical new project with an ethical dimension and urgency, this text challenges the ways scholars have viewed Byzantine society and culture.

I was branded as a tramp, tart, slut, whore, bimbo, and, of course, that woman […] When this happened to me seventeen years ago, there was no name for it. Now we call it cyberbullying and online harassment.

Before the reader even encounters the main text, the beginning of Byzantine Intersectionality packs a punch. Traditionally intended to suggest a book’s theme, Betancourt’s choice of epigraph is not from a historic text but rather is an excerpt from Monica Lewinsky’s powerful TED Talk, ‘The Price of Shame’ (2015). The Lewinsky quote sets an emotional and evocative tone by immediately forcing the reader to confront the modern/medieval issues and themes at stake in Byzantine Intersectionality, where ‘slut-shaming’, name-calling, harassment and gender politics are revealed to be non-modern constructs.

As is made clear from the book’s title, Betancourt deploys the sociological methodology of intersectionality to frame the narrative of his book. Coined by Law Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, ‘intersectionality’ is intended ‘to stress that the lived realities of marginalized people do not exist as isolated factors alone but instead come together at the intersection of gender, sexuality, race, socioeconomic status, and so on. Thus, intersectionality looks at how the overlap of social identities creates unique conditions of inequality and oppression’ (14). Such an approach acknowledges that these marginalised figures are not merely the sum of their parts; they are more complex and nuanced than easily categorised identifiers. Differing forms of privilege, privacy and agency begin to surface as one starts to intimately examine the lives of figures subjected to multiple inequities, or those who were historically vilified and marginalised, exposing ‘the greatest lacunae in the historical record’ by bringing acute awareness to these hidden intersectional figures (15).

The book follows Elizabeth Freeman’s argument that queer history necessitates ‘the decision to unfold, slowly, a small number of imaginative texts rather than amass a weighty archive of or around texts, and to treat these texts and their formal work as theories of their own, interventions based upon both critical theory and historiography’ (Freeman quoted on page 16). Accordingly, Betancourt searches both what is within the archives as well as what is lacking – the absences and erasures in the historical record. Acknowledging the potential danger of appearing anachronistic or revisionist, Betancourt clearly states that he will ‘endeavor (as much as [he] responsibly can) to read the figures in [his] texts and images as possible medieval subjects with a past, present, and – most important – a future’ (17). The use of ‘endeavour’ and ‘possible’ are critical in Betancourt’s project for they allow a margin for error and interpretive flexibility regarding the subjectivities encompassed in his text, while simultaneously acknowledging that ‘to deny these realities is to be complicit with violence – both physical and rhetorical – not just in the past but also in the present’ (17).

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Mosaic showing Empress Theodora and attendants, completed in 526; Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna’ by Richard Mortel licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Byzantine Intersectionality is composed of five chapters, each of which build upon the other while also functioning as its own minuscule intersectional history. In his first chapter, Betancourt explores the Virgin Mary’s consent in the Annunciation, the moment where the archangel Gabriel appears and announces to the Virgin Mary that she would divinely conceive the Son of God. Betancourt carefully reads the details and nuances of body language, textual rhetoric and iconographic tropes in paintings, manuscript illuminations, hymns and sermons. In taking the time to intimately read these narratives, Betancourt follows in the footsteps of early Christian and medieval writers by asking the critical question of ‘What is the Annunciation?’ and ‘What is the role of Mary’s consent in becoming the Mother of God?’

The second chapter attempts to recuperate Empress Theodora from the derisive ways that contemporaries spoke of her, especially sixth-century Byzantine historian Procopious of Caesarea in his difficult text, The Secret History. Theodora has been marked by historians as not only the viciously brutal wife of Justinian I, but also as a salacious figure inclined to immense and irredeemably grotesque debauchery. Thus, Betancourt uses the modern term ‘slut-shaming’ as a way to understand how individuals spoke about Theodora, hoping such an interpretation will liberate her from some of the shame imposed upon her.

Chapter Three considers the lives of transgender saints, while the fourth explores the visual and textual homoerotics of ‘The Doubting Thomas’, an episode from the Gospel of John wherein the resurrected Christ appears before the Apostles, encouraging sceptical Apostle Thomas to touch (or ‘thrust’) his hand to Christ’s open spear wound as proof of Christ’s Divine Majesty. Both of these chapters unveil the importance of sex and gender in all their manifestations within medieval culture, society and theology.

The fifth and final chapter, ‘The Ethiopian Eunuch’, functions as a sort of capstone for the Byzantine Intersectionality project, bringing together each of the previous chapters’ micro-histories into the experience of a singular intersectional body as depicted in a single image, ‘Philip and the Ethiopian Eunuch’, from the Menologion of Basil II, a text commissioned for the Byzantine Emperor around the year 1000. Betancourt does a beautiful job of navigating these texts by not overemphasising their potential sensationalism, instead presenting these lives as stories that are set forth for understanding marginalised medieval subjectivities.

Perhaps one of the most contentious, as well as most compelling, chapters is Byzantine Intersectionality’s third chapter, ‘Transgender Lives’, which discusses narratives concerning transgender saints by looking into how these figures provide models for understanding what a transgender identity might have looked like in this period. To achieve this, Betancourt uses ‘transgender’ as an umbrella term, borrowing from David Valentine’s ethnography of the transgender category in order to encompass a ‘range of gender-variant lives and practices’, even if these figures would not have claimed the label for themselves.

This tension between self-identification and identification projected by others is critical in this project because it highlights how the politics of identification is shaped by and through social power relationships. Crucially, Betancourt is clear that the ‘extant sources’ cited within his book ‘do not provide enough information to support an argument that any of these people felt their gender identity did not match their birth-assigned sex in the way that this subjectivity is simplistically imagined today’ (91). This again reaffirms Betancourt’s opening thesis that he will read these historic figures as possible intersectional subjectivities. He traces the transgender Life of Marinos, a figure assigned female at birth who proceeds to live his life as a male monk (understood as a eunuch in the Byzantine sources); Pelagius, the sex worker who becomes sanctified after transitioning to live an extremely ascetic life as a male eunuch, ultimately dying from ‘masculinising’ emaciation; and the depiction of Roman Emperor Elagabalus (also known as Antoninus) and her gender-affirming surgery in Dio Cassius’s Roman History. Each figure functions as an opportunity to illuminate forgotten lived experiences, experiences that ripple through into our present moment.

In reading Byzantine Intersectionality, an immensely gender-diverse empire with exceptionally complex approaches to gender manifests itself, and the text also begins the recovery of medieval conversations around sexual and reproductive consent, sexual shaming and bullying, sexual attraction and desire as well as bodily identification. This radical, innovative text provokes from the epigraph by Lewinsky to the final sentence with its ethical imperative for social and racial justice.

As Betancourt argues, to suggest that this text articulates or promotes anachronistic readings of history through its exposure of forces of silencing and erasure signifies complacency with marginalisation and oppression (207). Rather, what this text does is utilise the contemporary methodologies of marginalisation, oppression and intersectionality to articulate historic inequalities. To deny that figures such as those mentioned in Betancourt’s book existed is to perpetuate the damaging delusion that sexual violence, transphobia, homophobia, misogyny and racism did not exist in the premodern world. Thus, the only way the present and future can begin to undertake systemic cultural change is by acknowledging the social inequalities of the historical past – for if intersectional lives are denied historic precedent, how can we ever expect to construct a liveable reality in the present or future? As a modern history of gender, sexuality and race in the medieval era, Byzantine Intersectionality provokes as much as it inspires, illuminating just how true William Faulkner’s words were: ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.