In Revolutionary World: Global Upheaval in the Modern Age, David Motadel brings together contributors to explore ten revolutions across time and space through a transnational, territorialised lens, from the Atlantic Revolutions to the Arab Spring. With the chapters providing ideal entrances into their respective revolutions, this exceptionally useful collection will prove valuable to those teaching and researching revolutions, revolutionary politics and global history, writes Thomas Furse.

Revolutionary World: Global Upheaval in the Modern Age. David Motadel (ed.). Cambridge University Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

David Motadel’s edited collection, Revolutionary World, fits within a growing literature that intersects international, global and intellectual histories. The book takes on ten revolutions across a variety of times and spaces, in chronological order from the eighteenth-century Atlantic Revolutions to the Arab Spring of the 2010s. Its breadth gives the impression that revolutionary politics is always seething away somewhere, whether it is in parliaments or barracks, seaports or public squares of towns, clandestine pamphlets or mobile phones. For space, this review discusses just four of the revolutions explored in the book. But to be sure, all of the chapters will be beneficial to readers.

Motadel calls for us to think about revolutions through a transnational, territorialised lens (5, 8-11, 36, 262). The collection critiques the almost commonsensical methodological nationalism that claims that revolution is primarily a national project – as if the Russian Revolution was just ‘Russian’. Instead, the book invites us to think that revolutions are metaphorically and literally transnational; they draw on and spread across borders, with no fixed centre or periphery. This is what gives them such powerful potential. It is little wonder that counter-revolutionaries likened them to ‘diseases’.

The collection’s territorialised perspective draws attention to the role of communication in revolutionary politics. Each chapter, in an implicit or explicit way, points to the centrality of communication, be this the written word, the radio, railway transport or Facebook. The Communards of the Paris Commune in 1871 were physically isolated from the rest of the world, but newspapers across the globe were talking about the Commune (101-103). That is what mattered. The Arab Spring, a moment of just four months in 2010-2011, was 30 years in the making and quickly spread in part because of social media.

Even the building of communications often lingers in the background of this transnational perspective of revolution. In his chapter on 1848, Christopher Clark uses the Ostbahn crisis (1846) in Prussia as a case in point. The Prussian state needed money to finance a new railway from the Rhineland to the Russian border, and so required the stamp from a new all-Prussian parliament (75). This parliament halted finance until the state conceded and gave it some power. Liberal revolutionaries saw an opening, and within two years, they made their attempted seizure of power.

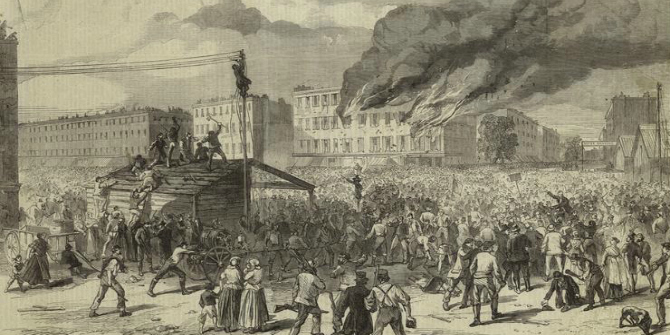

Credit: The dance of death: Death is seen as hero of the Revolution who passes his sword to the people. Woodcut by G.R. Steinbrecher after Alfred Rethel, 1848. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

The book covers the ‘grand revolutions’ that are already quite well known to most Anglophone audiences. The smaller ones do not feature, such as the long-running Batavian Revolution in the Netherlands in the eighteenth century, the Neapolitan Revolution in 1799 or Siad Barre’s quasi-revolutionary military coup in Somalia in the twentieth century. For those inclined, these revolutions could certainly feature in future research given the book’s territorialised perspective. The chapters in the collection are nonetheless exceptionally useful and this makes up for the inevitable gap that any book would have, other than an encyclopaedia.

Revolution is, in most cases, the dramatic use of power and violence. The military often features in this. Charles Kurzman’s chapter on revolutions in 1905-1915 tells a short fascinating story of the Ottoman Empire. A collection of junior officers and their civilian compatriots led the ‘Young Turk Revolution’ to overturn one constitution for an older, more democratic one. Yet when the Young Turks got to power, they turned on each other and those positioned as outsiders. They morphed into the Committee of Union and Progress, a domineering party that consolidated power through militant nationalism, modernisation and internal repression; later the regime headed the Armenian Genocide. The Young Turks’ capture of the state in July 1908 snowballed into the Ottoman Empire’s successor states (for instance, Syria and Iraq), where military arbitration settled intra-state politics into the late twentieth century.

Putting histories of different revolutions together makes the reader think about the similarities and differences between them. Clark’s chapter on the European revolutions of 1848 and James L. Gelvin’s chapter on the Arab Spring of 2010-2011 have similar tragic arcs. Clever reactionary governments forced the revolutionary opposition to blink and made smart necessary compromises to sap the hope and energy from mid-nineteenth-century liberal nationalists and the Arab street protesters. Autocratic states in Europe forced the revolutionaries into isolation as their armies moved across Europe. For instance, Hungarian liberal nationalism fractured disastrously into many competing nationalisms. Eventually, 200,000 Russian soldiers, requested by the Austrian emperor, ended the revolution. 162 years later, a Saudi Arabian-led military force entered Bahrain to end the Shia uprising.

Gelvin finds that the Arab Spring was probably doomed from the start. In North Africa and the Middle East, the revolutionary opposition groups were not united on much other than a hatred of the ruling regime. They lacked coordinated organisation and a robust ideology to overturn the ruling neoliberal orthodoxy that Gelvin finds crucial to understanding the Spring. Ultimately, the end of the regime was easier to imagine than the end of neoliberalism.

In Clark’s and Gelvin’s chapters, transnational revolutionary movements are weak because they are primarily horizontal networks (78). Bahraini Shia revolutionaries might have been connected to those in Saudi Arabia, but to what end? In contrast, governments have mutual interests in containing any revolutions. The fear of losing something seems to forge a deeper connection than diverse national and ideological groups hoping to gain power in different localities. Those with steel sabres and armoured personnel carriers won the day.

And yet, state coercion alone is not enough, and there is great strength in transnational revolutionary politics. John Connelly’s chapter argues that the anti-communist revolutions of 1989 were battling grim communist regimes that staggered into the 1980s. Eastern Bloc states had vast, albeit knackered, security and surveillance services to draw on in their bid to stop revolutions. But 1989 was a moment when pre-existing social and political forces collided with increasingly weakened states that had, in some cases, lost the will or ability to continue.

Connelly locates an interesting detail about how revolutions can unfold from banal regulations. In 1989-1990, Hungarian leaders needed to replace sections of rusty fences and mines past their explosion date on the Austrian border (227-28). The military hardware was a cost the state could ill-afford, and Hungarians and Austrians were moving freely across anyway. The state did not replace them and, quite suddenly, a new reality existed: the militarised borders that kept Western capitalism out and buttressed state socialism became pointless. This chimed with what was going on elsewhere. Günter Schabowski, the East German Politburo member, improvised the timing of travel regulations that mistakenly launched a mass movement at the border. Crowds at the Berlin Wall border stations overwhelmed the guards.

These Eastern Bloc revolutions were not of the same, but they converged at the crucial moment when regimes were seeking ways out. There were compromises between the regime and opposition in Poland and Hungary, street protests and worker strikes in East Germany and Czechoslovakia, protests followed by a regime-led push for democracy in Bulgaria and finally, in Romania, the army eventually turned and shot President Nicolae Ceaușescu on TV on Christmas Day 1989.

A question that arises from this transnational territorialised history of revolution is how deep revolutionary politics are across spatial and temporal contexts. Rachel G. Hoffman’s chapter alludes to this point, where she notes that communist revolutionaries in the 1920s were sometimes more enamoured with slogans than political thought. Can we measure mimicry in revolutionary inspiration? Where would-be revolutionaries take the slogans and thrill-seeking dramatism of politics from a genuine revolution but do not practise any functional change when their moment arrives.

If there is one criticism of the book, it is that the chapters rarely dwell on revolutionary characters. We often miss out reading about aristocratic renegades and dreamers, the earnest intellectuals and chancers that make political upheavals happen. These figures have given flavour to revolutions from the eighteenth century to the contemporary moment. They can draw us in to read more. Lenin’s intellect, Ahmed Niyazi’s charisma and Khomeini’s religious zeal change how transnational and inspirational a revolution could be. For some, demonic ideas possess these individuals; for others, they are guiding stars that liberate the people from oppression.

Nevertheless, this minor point of emphasis should not discount the analysis that lies within the collection. Those teaching courses on revolutions, revolutionary politics and global history would do well to reference this book. All the chapters are ideal entrances into their respective revolutions, and the extensive footnotes (particularly in Motadel’s introduction) are useful for those wanting further reading.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.