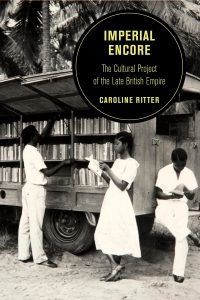

In Imperial Encore: The Cultural Project of the Late British Empire, Caroline Ritter explores how cultural industries were used as part of the strategy to extend the life of the British Empire in Africa, focusing on the 1930s to the 1980s. This text should be on the reading list of anyone interested in colonialism, material culture as a tool of empire and attempts to extend imperialism through the use of soft power, writes Lori Lee Oates.

Imperial Encore: The Cultural Project of the Late British Empire. Caroline Ritter. University of California Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

In Imperial Encore: The Cultural Project of the Late British Empire, Caroline Ritter demonstrates the extent to which cultural industries and soft power were used, not only as tools of empire, but also as key aspects of the strategy to extend the life of the British Empire in Africa. Her methodological approach effectively situates the book within the expanding body of research on the importance of cultural products as instruments of empire-building. With a focus on 1930 to 1980, Ritter examines how aspects of material culture, such as drama performances, broadcast services and publication bureaus, were employed, under the guise of colonial development, to extend the imperial project. Furthermore, she maintains that this was done in ways that would not seem obvious without examining these various media side by side and in their totality.

In the introduction, Ritter argues that ‘the political history of the end of the British Empire must be realigned with a cultural history of reinvigorated imperial ambition’ (6). While it is true that cultural history can inform our understanding of political history, this is far from a novel idea. However, Ritter does bring something new to the discussion. Her main accomplishment is putting broadcast media, travelling theatre troupes and print runs of books together, in order to demonstrate ‘how the same group of cultural artists and even the same relatively small canon dominated British cultural outreach to Africa’ (7). In doing so, she demonstrates the social cohesion of British cultural agencies, both in recognising the importance of empire and in acting in concert to preserve it. The book is divided into two parts: one which deals with ‘late empire’ and the other covering ‘after empire’.

Building on the work of Edward Said in Culture and Imperialism (1993), Ritter demonstrates how ‘the postcolonial critique did not disarm British cultural imperialism – in fact, it ran alongside and sometimes even strengthened it’ (9). Drawing on primary sources, she shows how British cultural agencies, including the BBC and publishing firms like Oxford University Press, maintained that they were ‘fostering African input and encouraging dissenting voices’ to demonstrate that such agencies were important to postcolonial society (9).

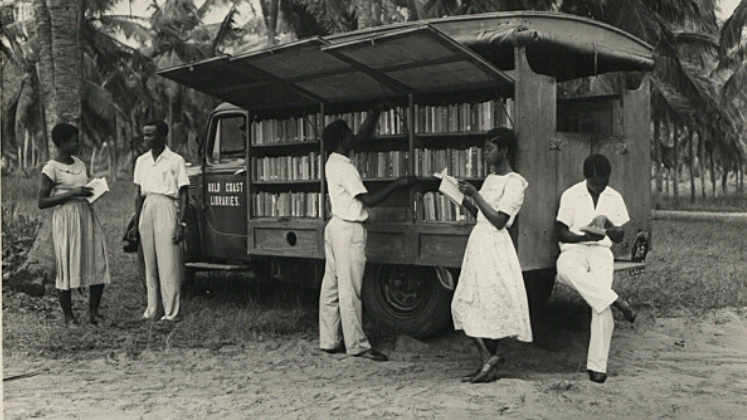

Image Credit: ‘CO 1069-43-73’ depicting users of a mobile library van, Accra, Ghana from The National Archives UK, no known copyright restrictions

The book argues in a compelling way that British officials originally tailored their outreach in East and West Africa to white settlers and elite audiences. However, they eventually began targeting black non-elite African populations. British officials maintained they wanted a positive relationship between Britain and Africa that would continue into the postcolonial period. This stood in contrast to how African writers and politicians would formulate their vision of the new postcolonial state. For these figures, what occurred was an ‘imperial encore, but one that showed no sign of ending’ (13).

For example, the British Council relied upon the prominent position of the works of William Shakespeare in curricula and exams to continue the export of drama to Africa. Today the British Council is a public organisation that facilitates cultural and education opportunities. It was founded in the 1930s ‘with the purpose of projecting national culture overseas’ (18). This included the development of stage shows by travelling theatre troupes that would bring the works of Shakespeare to the colonies. It also offered opportunities to learn English. Ritter frames this as ‘using one expression of hegemonic power to justify another’ (45). Conversely, during the same period, Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka argued that it was crucial for ‘East and West Africans to think imaginatively beyond ”the dictates of the British Council pre-historic strictures”’ (46).

In Chapter Three, Ritter examines BBC broadcasting. The BBC ‘started domestic broadcasting in the 1920s and inaugurated its external broadcasting arm, then named the Empire Service, in the early 1930s. The latter was built on shortwave, a relatively new discovery that allowed broadcasters to transmit over long distances cheaply’ (72). This is not surprising, as the structures of communications were often used to extend colonial reach. Like the telegraph, steam ships and railroads before them, new radio technologies were put into the service of empire.

Local audiences were not a priority for the BBC. Ritter maintains that it was only after the Suez Crisis in 1956 that Britain dealt with decolonisation by directing itself towards indigenous audiences in East and West Africa. She makes the case that with African independence, for the first time the BBC found themselves ‘having to compete for postcolonial listeners at the very moment the audience had become most crucial’ (73).

‘Books in all their variety are the means whereby civilization may be carried triumphantly forward.’ This 1937 quote from former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill is the opening for the second chapter, ‘Bringing Books to Africans: Publishing in Colonial East Africa’. It was within the colonies that these words would become a policy approach. Ritter maintains that ‘at that precise time, British publishers had started showing interest in expanding their industry reach, particularly in Asian and African colonies, where they imagined endless untapped markets. They seized upon and started repeating Churchill’s words as testimony that there was more purpose to their work than just markets and profits’. In their minds, ‘the British publishing industry had a central place inside the grander civilizing mission’ (47).

In the three decades after its founding, the British Council ‘grew from a handful of departments and representations around the world to an organization with thousands of officials who worked in seventy territories, including twenty in Africa’. Officials were rotated between London and overseas nations every three years. Ritter sees this as a reflection of the British Council not caring to hone regional expertise among its officials (19). She also describes how British Council committee members ‘represented a London-centred, elite version of the stage which they had clear financial, political and cultural interests in preserving’ (25).

Support for the Empire was seen as an issue of safety for British civil servants in Africa. After the Second World War they ‘expressed increasing levels of concern about the ferocity of popular politics in sub-Saharan Africa’. Ritter maintains that ‘when the governors looked to Whitehall for [security] support, they often found it – or at least encountered little resistance’ (92). This included a vision for a ‘broader minded approach’ to news. Colonial administrators felt that by developing political institutions they could use the public sphere to mitigate demands for political change (92).

Ritter concludes that ‘British cultural imperialism reinvented itself as a new version of global Britishness. Its elements overlapped with Western values more generally, such as freedom of speech and the press that ethical journalism and competitive publishing both celebrate’ (190). This was built on the idea that ‘revered and unquestioned Britishness’ could be a universal good. She argues that ‘the imperial endeavour is still very much present, fueled by cultural self-confidence that guides – some would say blindly – the role Britain still seeks for itself in the world today’ (191). This conclusion is even more compelling when seen in light of the discussions around Brexit and British exceptionalism that have taken place in recent years. All of this makes Imperial Encore a text that should be on the reading list of anyone interested in colonialism, material culture as a tool of empire and attempts to extend imperialism through the use of soft power.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.