Drawing on his chapter in the collection Narrative Expansions (edited by Jess Crilly and Regina Everitt), LSE Library’s Academic Liaison and Collection Development Manager Kevin Wilson discusses the impact of decolonisation on collection development and issues of bias within library collections. By working with academic staff and students and involving them in developing collections, this can increase inclusivity and representation, whilst encouraging a sense of ‘shared ownership’ and showing that library collections belong to us all.

If you are interested in this piece, you may also like to read Jess Crilly’s recent LSE RB post introducing Narrative Expansions. You can also explore resources on decolonisation in higher education at the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa’s Decolonisation Hub.

Demands to decolonise Higher Education have increased across the world in the last decade. The Rhodes Must Fall protest movement at the University of Cape Town triggered demands for action at other universities in South Africa, the UK and the US, and started debates about how universities were founded and funded, the nature of their curricula and how racial discrimination continues to exist. This coincided with a rising awareness of racial injustice and police brutality that further grew in the summer of 2020 with the global protests that followed the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the US.

Academic libraries have started to reflect and review their own services, processes and strategies through an equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) lens. Narrative Expansions is one of the first titles that captures the broad range of work that has taken place in academic libraries, both in the UK and worldwide. Some of the issues discussed in this new book include the experiences of BAME staff, information literacy and research methodologies, cataloguing and classification, and collections. I contributed a chapter to the volume that explored the impact of decolonisation on collection development and issues of bias within library collections, discussed the composition and balance of LSE Library’s collections and made practical recommendations for librarians who want to enact change.

When discussing the impact of decolonisation on library collections, we should probably reflect on what we mean by collection development. In essence, it is the work undertaken to build library collections and the decisions taken that determine how they evolve. Most librarians agree that the purpose of library collections is to reflect and support the teaching and research needs of their parent institution, although libraries are increasingly questioning whether they should remain passive or instead should become bolder and prepare to support efforts to diversify the curricula.

Librarians often view themselves as impartial custodians of collections and gatekeepers to information (and we are one of the most trusted professions in the UK). Despite our good intentions, we should reflect on our own decision-making and ask ourselves whether we are truly neutral, and even whether neutrality is desirable as this may just perpetuate existing inequalities. As librarians, we need to step out of our comfort zone and reflect on our assumptions and beliefs about balance and fairness and accept that unconscious bias can affect how we develop collections. This can be a personal and professional challenge. There are always risks when decisions are made by a few individuals making judgments, so one suggestion is for more collaborative collection development, with a plurality and diversity of voices and experiences involved in selection. Working with academic staff and students and involving them in developing collections can increase inclusivity and representation, whilst encouraging a sense of ‘shared ownership’ and showing that library collections belong to us all.

Libraries should actively commit to greater diversity, work with their university’s EDI teams and align themselves with university strategies (or go beyond these if change is too slow). It’s important that libraries take the time and dedicate the resources to systematically reviewing their collections, so they can acknowledge collection strengths and redress collection weaknesses. This can be done by taking a data-driven approach, looking at the geographical spread of collections, as we’ve done at LSE Library.

We discovered our collections are highly dominated by Global North countries (particularly the UK, US and Western Europe). In comparison, our collections are less represented by countries from Africa, Asia and Latin America. Upon learning this, we can now be more proactive in developing collections that include more marginalised and underrepresented groups, using new suppliers and publishers. We can also support academic staff who want to diversify their reading lists. There are particular concerns about gender and race bias in reading lists in some social science disciplines, such as International Relations and African Studies. These biases may in part reflect the biases in our collections, so it’s particularly important that libraries change their collection development approaches, develop more representative collections and give academic staff as much opportunity as possible to diversify their own lists.

Addressing biases in how we acquire books is merely the start. We need to think more deeply about how these collections are described to and discovered by our library users. Take an example: a student might type something like ‘United States immigration’ into a library catalogue and they receive a long list of results. What we know less about is how and why the subject headings that make these books discoverable have been assigned.

Recently, librarians have expressed concern that the language used to describe titles is often offensive. In the US, there was huge controversy over the use of the term ‘illegal aliens’ in the Library of Congress classification scheme. Following lobbying from librarians at Dartmouth College, the Library of Congress agreed to change this term in 2016, but the then Republican-dominated House of Representatives vetoed this. Just last year, a compromise that replaced ‘illegal aliens’ with ‘noncitizens’ and ‘illegal immigration’ appeared to please nobody on either side of the debate. There is an excellent documentary about the Dartmouth campaign called Change the Subject that you can watch in full online.

This is an example of just one of many terms that are outdated or discriminatory towards already marginalised groups according to race, gender, sexuality or disability. Librarians continue to raise awareness and campaign for change but face institutional resistance. The changes librarians can make to classification may be small, but they are significant, including ‘cultural sensitivity’ messages on library catalogues to acknowledge historic and outdated language.

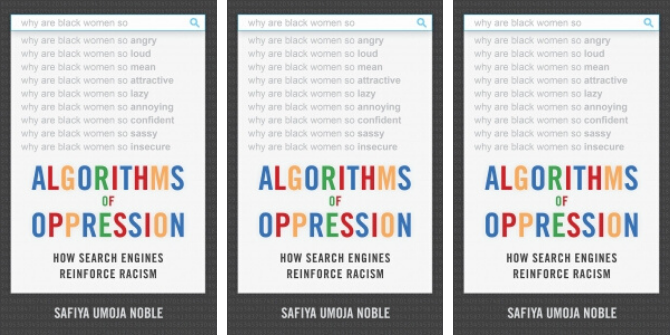

Looking beyond libraries for a moment, we know gender and racial bias dominate internet search engines too. In December 2020, a former Google employee, Timnit Gebru, was fired for co-writing a paper on the ethics of artificial intelligence that asked whether it reinforces gender bias and offensive language. The 2020 documentary, Coded Bias, further explored how algorithms and artificial intelligence discriminate according to gender and race.

Concerns have been raised about bias against LGBT+ communities, Islam, race and mental illness in search engines and library catalogues. When you search online for information on any subject, you may expect to find material of varying quality, sometimes with dubious motives and agendas, and you need to constantly think critically. We inform students our libraries provide access to peer-reviewed research that has been rigorously assessed by experts before publication, but students need to think just as critically because library catalogues usually retrieve results by ‘relevance’, which can be undefined and arbitrary. It’s important that librarians better understand the algorithms underpinning catalogues and databases and ask for clarity on how results are indexed and ranked, rather than assume they are bias-free.

Researching and writing this chapter has confirmed that we cannot take library collections – how they are developed, described and discovered – at face value. We need to confront the biases that exist within those collections and, often, ourselves. This liberates us to take affirmative action to improve the experience for our users. More broadly, it is reassuring to see the great work taking place across the entire academic library sector, and to discover that every aspect of the profession is being reflective and creating change. For librarians and non-librarians alike wanting a starting point on how decolonisation is making a difference to academic libraries, then Narrative Expansions is a superb choice.

Note: This blog post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.