In Narrative Expansions: Interpreting Decolonisation in Academic Libraries, editors Jess Crilly and Regina Everitt bring together contributors to explore the variety of creative initiatives undertaken by academic libraries and archives to open their doors to underrepresented voices. This timely collection is a brilliant effort to unite the thinking behind the movements to decolonise the curriculum, writes Amy Lewontin.

If you are interested in Narrative Expansions, you can also read editor Jess Crilly’s LSE RB blog post introducing the collection as well as a piece by LSE Library’s Kevin Wilson drawing on his contribution to the volume.

Narrative Expansions: Interpreting Decolonisation in Academic Libraries. Jess Crilly and Regina Everitt (eds). Facet Publishing. 2022.

A new and timely collection, Narrative Expansions: Interpreting Decolonisation in Academic Libraries shifts the emphasis of decolonising the university to a hands-on view of the variety of creative initiatives undertaken by academic libraries to open their doors to underrepresented voices. Jess Crilly and Regina Everitt, both library managers in the UK with experience overseeing larger research libraries as well as archives, edit and introduce the fifteen essays by librarians and archivists from around the globe.

A new and timely collection, Narrative Expansions: Interpreting Decolonisation in Academic Libraries shifts the emphasis of decolonising the university to a hands-on view of the variety of creative initiatives undertaken by academic libraries to open their doors to underrepresented voices. Jess Crilly and Regina Everitt, both library managers in the UK with experience overseeing larger research libraries as well as archives, edit and introduce the fifteen essays by librarians and archivists from around the globe.

Early in the book, in a conversation on decolonisation and activism that the editors have with the National Union of Students’s Vice President, Hillary Gyebi-Ababio, she mentions the library’s role on campus. As Gyebi-Ababio explains, ‘dismantling the academic canon and expanding and transforming the library as we know it is a part of the decolonisation process that can produce immediate change and engage people for longer-term change. The library is a place of discovery, of investigation.’

This role of the library as a place of discovery and an active force for positive change for students and university staff is clearly demonstrated throughout the essays in Narrative Expansions. This book should be a first port of call for academic librarians and faculty across university departments who seek to support their institution’s wider efforts at embedding anti-racism within the curriculum, as well for those working to achieve more diversity and inclusion in the scholarly material provided for their academic community. Contributors to Narrative Expansions come from a wide geographic and institutional cross-section of academic environments, yet all share a common purpose: to work with others across their universities to examine a colonial and mainly Eurocentric past and forge solutions unique to their institutions.

Image Credit: Pixabay CCO

Narrative Expansions is divided into two quite distinct sections. In the first, ‘Contexts and Experiences’, contributing authors give the reader a grounding in the current political environment at their respective universities and where the library fits into the larger academic research context. The second section of the book, ‘In Practice’, encompasses many more chapters. Here, the contributing authors take a practical approach and explain their efforts to apply the theory locally. This second section has much to offer for those seeking ideas for their own initial efforts.

In the case of 21st-century academic libraries and archives, this means an examination of what has been and currently is available to library users: namely, books and journals as well as archival materials on both physical and now digital shelves. In their descriptions of what is presently on offer at academic libraries, many of the contributing authors discuss the Indigenous voices that have been missing from libraries and their plans to rectify those gaps.

In pinpointing whose voices are missing and unique approaches to expanding and enriching scholarly offerings by respecting and encouraging those missing voices, this collection is rather unique in the context of library literature. Marilyn Clark, Director of Library Services at Goldsmiths, University of London, describes the work that library staff undertook with students and faculty ‘to identify the excluded voices and lived experiences, and to highlight Global South scholars missing from curriculum reading lists’. This project, the Liberatemydegree book collection, was one way of addressing a serious lack of collection diversity. It was a collective approach that contributed to a change in the direction of what Goldsmiths Library purchased and many of the books found their way onto curriculum reading lists soon after being acquired.

Narrative Expansions is not limited to an examination of the whiteness of scholarly research collections. Several essays examine increasing student diversity at their universities and point out the serious need to improve diversity and career progression within the library and archival profession. Crilly and Everitt clearly explain the larger aim of the volume in their introduction: ‘The work of decolonising the library is about understanding how the past has informed the present, but must also be about envisaging a better future, even if how to achieve it isn’t always clear’ (28).

What is most valuable about reading the essays is that they enable readers to gain an understanding of how each institution took its own approach, generally a step forward; yet the authors explain that their work is part of a continuous process, not yet finished, but useful for wider discussion and local sharing of ideas. Ludi Price, in her essay on efforts to decolonise the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Library, explains what this means for her institution and I think for many others: ‘decolonisation is a dynamic process, and as the group navigates, and critically reflects upon, its practice, these goals may be subject to modification. None of us claims to be expert in what it means to decolonise; but we are dedicated to learning what it means through an ongoing journey, both within and without our home institution’ (282).

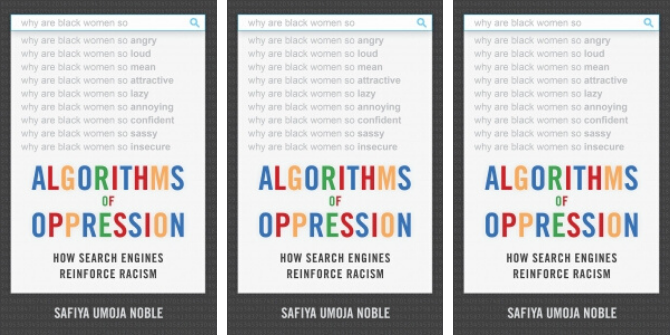

Narrative Expansions takes the reader into many areas of the library, including cataloguing, classification and automation, to consider how and why there may be underrepresented voices. Several essays, including the contribution from Clark on Goldsmiths Library, briefly explore the idea that commercially purchased library automation systems as well as traditional library classification schemes have racial biases built into them. Other authors within the library field have recently explored the biases of automated library systems: for example, Masked by Trust by Matthew Reidsma, and perhaps the better known recent work Algorithms of Oppression by Safiya Umoja Noble, who mentions ArtStor, a library resource for searching millions of digital images. Noble refers in her book to searching for ‘black history’ in ArtStor and finding the results returned were European and white American artists (Algorithms of Oppression, 146). In Kevin Wilson’s illuminating essay on decolonising the collection at LSE, he refers to the firing of Google researcher, Timnit Gebru, in December 2020, ‘for co-authoring a paper on the ethics of artificial intelligence and whether it reinforces gender bias and offensive language’ (303).

While the essays in Narrative Expansions take on traditional aspects of the library, with cataloguing and collection development quite thoroughly covered, there are some areas that a future volume might explore. Several authors refer to the control that larger publishers exert over who is published, and how this can diminish and marginalise voices that should be heard. Wilson mentions that the majority of university library budgets is now going to the largest publishers, who are monopolistic in practice (289).

What is left unsaid in the various essays is that libraries can take an activist approach to reach out directly to publishers. Also unmentioned in the book is how much money is now spent with these same monopolistic publishers, buying access to electronic research tools for a multiplicity of academic purposes. Many of these electronic tools lack a way to search for diverse voices. My colleagues at Snell Library at Northeastern University in Boston, MA, designed an assignment for students to research and profile engineers with diverse backgrounds so that students could ‘see themselves’ in STEM fields. They discovered challenges across the biographical databases to which we subscribe: minimal representation, limited usability and very few profiles of BIPOC and women engineers. As a library group, we reached out to many of the larger publishers of the research tools and had several constructive dialogues with editors, as we suggested ways to improve findability in the tools that we subscribe to.

Narrative Expansions, with its international perspective that includes authors from Africa, the US and Indigenous Métis librarians from Canada among others, is a brilliant effort to unite the thinking behind the movements to decolonise the curriculum. It illustrates the dynamic and continuous efforts that academic libraries and archives are undertaking worldwide to interpret decolonisation for their own situations and contexts.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.