In Macroeconomics: An Introduction, Alex M. Thomas offers a new overview of the development of macroeconomics, combining concepts with real-world examples drawn from the Indian economy. In linking economic ideas with real-life issues, Thomas succeeds in his goal of enabling readers to grasp the daily life of macroeconomics, writes Kaibalyapati Mishra.

Macroeconomics: An Introduction. Alex M. Thomas. Cambridge University Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

Macroeconomics: An Introduction by Alex M. Thomas is an excellent attempt to make its readers aware of the evolution and application of economics that happens around them, frames news headlines and shapes dinner-table gossip, combining concepts with specific reference to the Indian context. Drawing on the dimensions brought into the realm of economic thinking by scholars over a long period of time across classical and modern textbooks, Thomas establishes economics as a discipline addressing the management of the individual, historical and political needs of the masses through the formation, accumulation and distribution of wealth.

Macroeconomics: An Introduction by Alex M. Thomas is an excellent attempt to make its readers aware of the evolution and application of economics that happens around them, frames news headlines and shapes dinner-table gossip, combining concepts with specific reference to the Indian context. Drawing on the dimensions brought into the realm of economic thinking by scholars over a long period of time across classical and modern textbooks, Thomas establishes economics as a discipline addressing the management of the individual, historical and political needs of the masses through the formation, accumulation and distribution of wealth.

The emergence of economics traces its roots back to the ages of Ibn Khaldun, Kautilya and Confucius, with its modern existence as the discipline of political economy unravelled in The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith. Economics, a field with multidisciplinary relevance, demonstrated its political implications and state role through works like General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by John Maynard Keynes, while continuing to touch on the different contours of classical economics presented by scholars like Thomas Malthus, J.S. Mill, Alfred Marshall and others.

Following the age of discovery in the eighteenth century, the major developments in economics in the twentieth century were monetarism, institutionalism and game theory. Thomas also highlights Piero Sraffa’s critique of marginalist economic principles and the textbook teaching culture in economics brought about by Paul Samuelson, seeing these as significant developments that gave birth to several new chapters in economics and its popular dissemination.

The two partially divergent strands of political economy relating to output and employment levels were labelled as the marginalist school and the Keynesian school. Borrowing from the thoughts of J-B. Say, Marshall and Arthur Pigou, the former school focused on the marginal productivity theory of income distribution, while the latter drew from the works of Michał Kalecki and Keynes. Though both schools studied the competitive economy under the assumption of a given level of productivity, differences were manifold. The Keynesian explanation of output and employment was based on the demand side, while the supply side dominated the marginalist school, which believed that ‘supply creates its own demand’.

Given the dynamic macroeconomy, where investment plays the dual role of being a component of demand (aggregate demand) and an addition to productive capacity, the book classifies theories of economic growth into clusters of supply- and demand-side theories. The supply side, with the aggregate production function as the workhorse, gained importance as the foundation of economic growth models developed by Robert Solow and Sir Roy Harrod. Paul Romer’s popular neoclassical theories then developed technology as an internal component of economic growth. On the other hand, bringing together classical and Keynesian versions of value, Pierangelo Garegnani developed the fundamental synthesis of demand-side theories of growth.

Thomas demonstrates the need for clarity in the modelling of economic problems. The book opines that mathematics adds clarity to economic models along with logical restrictions. For example, calculus (a workhorse for the mathematical foundations of marginalist economics) adds to the potential change of several economic values including cost, revenue and productivity. The importance of an appropriate and adequate number of variables is also evident as policies based on underfitted models with fewer variables than required can yield inefficient results.

The contrasting views of methodological individualism or holism (deriving findings from the observation of individuals or groups), supported by marginalist and Keynesian theories respectively, have raised the question of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ theories. Here, Thomas explicitly aligns himself with the holistic approach, like Keynes himself, who opined that methodological individualism yields flawed results in understanding macroeconomics.

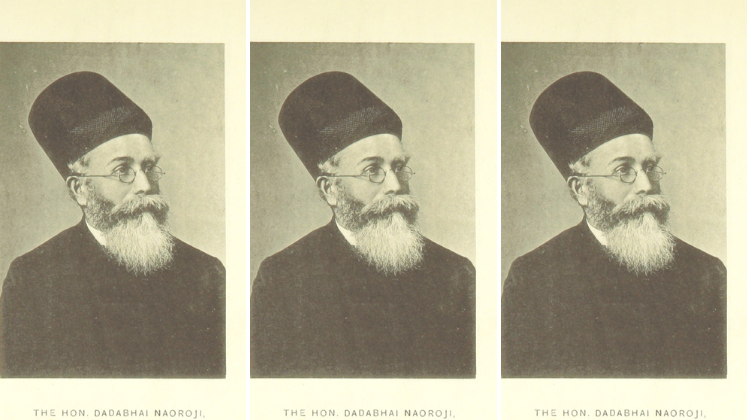

As the book outlines economics as a science of wealth that presents a macro picture, Thomas identifies the embryonic inception of National Accounts Statistics (NAS) in the works of William Petty. This was later followed by the United Nations-mandated regulations of the System of National Accounts (SNA). The Indianised version of the SNA, indigenised by Dadabhai Naoroji, V.K.R.V Rao and P.C. Mahalanobis, still suffers from overlooking women’s contributions and the ecological costs of wealth generation. The book also discusses the classification of different sectors of the economy and relations between them, along with the sectoral flow of funds. This represents the ideas of interdependence and the circulation of wealth in the economy.

The strength that this work has in comparison to existing textbooks on macroeconomics is in its examples taken from the real world, both from India and across the globe. Rao, among the leading economists in India, brought Keynesian theories back into the framework of developmental economies. Along with A.K. Dasgupta, he established that the Keynesian framework still has limited applicability to India, given the supply-side constraints of inadequate physical and social infrastructure and labour market discrimination. Given the government’s current emphasis on self-sufficiency (Atmanirbhar), Thomas highlights the need for India to produce outputs at lower cost than the rest of the world, thus reducing dependency arising out of export markets and bilateral trade agreements.

Thomas vividly outlines India’s growth trajectory regarding historical inequalities, sectoral performance, job creation and ecological impacts. India’s distribution of land holdings is exemplary of historical inequalities. The percentage of households with large land holdings is as low as 0.24 per cent (against 75.42 per cent of marginal farmers); however, the average land holdings of these households is 14.4 hectares (against 0.234 hectares for marginal farming households). Once the backbone, but today the backward sector, of the Indian economy, agriculture makes minimal contributions to total national output, being significantly outweighed by the manufacturing sector, but of all services, it still seems to dominate.

Contextualising the structural aspects of the Indian economy, Thomas therefore argues that any discussion of the Indian macroeconomy has two major segments: firstly, the importance of agriculture; and secondly, the presence of an informal sector. Unlike developed countries, Indian agriculture is characterised by the functionalities of village economies that suffer immensely from spatial inequality and are rarely explained by any economic theories. Societal constraints of caste, gender and race affect the regional distribution of natural resources and ownership of land – essentially all elements of formulating policy. The presence of informality also adds to the precarity of inequality in village economies.

The GDP growth of India has excelled; however, inertia in generating jobs is evident from the fractional growth in employment. The ecological standpoint of the country’s growth is observed from CO2 emissions and India’s carbon footprint, wherein huge inequality is prevalent. Individuals and organisations who benefit the most from these emissions are the ones paying the least and the poor seem to bear the significant environmental burden.

The book justifiably discusses the two major issues of employment and inflation in India as they lead the agenda on national economic policy prescriptions. Decisively dividing the macroeconomic issue of employment into quality and quantity, Thomas presents the need to address both these dimensions for an aspirational level of full employment. Moreover, regular household chores usually done by women are not part of national accounting as they are yet to be considered ‘work’. Recently, the published Time Use Survey of India made a rudimentary attempt at incorporating women’s work as part of national income accounting (NIA); however, it did not give economic valuation to such labour. In terms of quantity, the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has been found to be influenced by social and cultural factors (such as caste, class, gender and so on), rather than solely economic ones. Similarly, the quality of employment is crucial given its huge non-monetary and psychological effects. This discussion establishes that merely considering the unemployment rate is not enough to capture the real picture.

The other flaw that every real economy tries to avoid is the inflationary tendency in prices. In India, Wholesale and Consumer Price Indexes (WPI and CPI) are the indicators of inflation, which is characterised by irrational and unexpected increases in prices. The base year for such calculations is still 2011-12, which fails to accommodate all the significant changes that have occurred since this period. Moreover, the stakeholders in the calculation of WPI and CPI need to revise their assigned weightage and include more products for better representation. Though Thomas does not address the structural issues of such indices, he highlights several generic policy recommendations for dealing with unemployment and inflation.

The benefit that this book has over several other excellent textbooks on macroeconomics (see, for example, Brian Snowdon and Howard R. Vane) is in its linking of basic economic concepts to real-life issues. Thomas does justice to the concepts and contexts that govern everyday macroeconomics. Drawing on the words of the father of the marginalist school, Adam Smith, this book demonstrates that ‘individual ambition serves the common good’ as Thomas succeeds in his goal of enabling readers to grasp the daily life of macroeconomics.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.