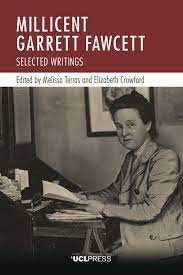

In Millicent Garrett Fawcett – available open access from UCL Press – Melissa Terras and Elizabeth Crawford offer a new collection of writings by the seasoned organiser, lobbyist and public speaker who campaigned for women’s suffrage. Contemporary feminists will take inspiration from the book’s evidence of the formidable fortitude, optimism, determination and generous spirit of activists like Fawcett, writes Sharon Crozier-De Rosa.

Millicent Garrett Fawcett: Selected Writings. Melissa Terras and Elizabeth Crawford (eds). UCL Press. 2022.

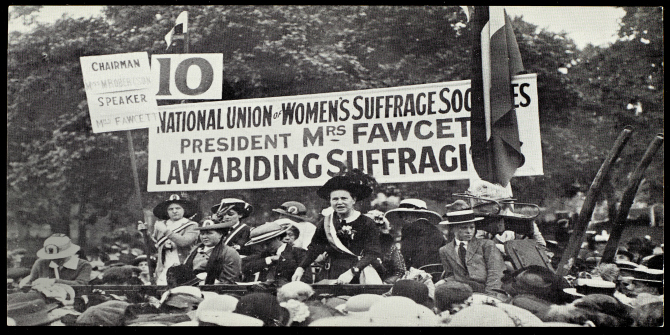

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act granted the vote to women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification. This reform was the result of five decades of sustained feminist campaigning. A woman who was active through all of those years was Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847-1929). From the onset of the women’s suffrage movement, she was a relentless and seemingly tireless organiser, lobbyist and public speaker. In its later years, she spearheaded it through her role as president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS, established 1897), an umbrella organisation for regional societies devoted to achieving women’s enfranchisement. It is reported that, by 1914, the NUWSS had over 500 branches and 100,000 members. However, despite evidence of the sheer breadth of her devotion to the cause, Fawcett’s name has been eclipsed in the public memory by her more provocative peer, militant suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928).

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act granted the vote to women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification. This reform was the result of five decades of sustained feminist campaigning. A woman who was active through all of those years was Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847-1929). From the onset of the women’s suffrage movement, she was a relentless and seemingly tireless organiser, lobbyist and public speaker. In its later years, she spearheaded it through her role as president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS, established 1897), an umbrella organisation for regional societies devoted to achieving women’s enfranchisement. It is reported that, by 1914, the NUWSS had over 500 branches and 100,000 members. However, despite evidence of the sheer breadth of her devotion to the cause, Fawcett’s name has been eclipsed in the public memory by her more provocative peer, militant suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928).

This collection of a selection of Fawcett’s writings, edited by Melissa Terras and Elizabeth Crawford, gives voice to an often overlooked seasoned political campaigner. In beautiful detail – captured in wonderful introductions to, and extensive endnotes for, each of the 55 chapters – the editors contextualise the social, political, literary and religious spaces that Fawcett moved through and which informed her worldview. At times, in the introductions for instance, the editors quote an elderly Fawcett looking back on the words of her younger self to great effect.

Image Credit: Crop of ‘Portrait of Millicent Garrett Fawcett, c1910 in Mary Lowndes Album 2ASL/11/02b’, LSE Library. No known copyright restrictions.

It is difficult to communicate a sense of the richness of this contextualisation, but let me try with one random example. In relation to a reference to hairdressing in Fawcett’s 1875 novel, Janet Doncaster, the editors explain that this referred to a speech given by women’s rights activist Emily Faithful (1835-95) in which she revealed that hairdressing had become a new occupation for women given that female hair-cutters now joined male barbers in London’s West End (endnote 6, page 91). (Did you even know that Fawcett wrote a novel, albeit one that renowned early chronicler of British women’s suffrage Ray Strachey (1887-1940) said was ‘not written with the skill of a great novelist’ (85)?) Such a dedication to researching all elements of the suffragist’s writing, even seemingly inconsequential details, renders Fawcett and her world more vivid, intimate and alive.

This is a very good thing because, as you might expect given that Fawcett was promulgating the same arguments for 50 years, many of her texts are repetitive and sometimes heavy-going. Still, such a characterisation does enforce for the reader just how enduring the suffrage campaign was, and it builds up a picture of the stamina required to see it out to the end.

The selection of Fawcett’s writings contained here demonstrate the diversity of her audiences and shows how skilled she was at crafting her addresses to appeal specifically to them. For example, Chapter 19 details a report of an invited speech which Fawcett presented to a Conservative London gentlemen’s club in 1897. At that time, she was only proposing legislative reform that would have seen approximately one million women added to an existing male electorate of about six million. Through adopting a humorous, almost self-deprecating approach to the radical reform that she and her peers were trying to push through, she reportedly diffused what she imagined were her listeners’ fears. You are not going to be out-voted by ‘a horde and rabble of women’, she claimed. ‘There really was nothing so very terrible after all – even to the most timid of the stronger sex – (laughter) – in the thought that for every six men there was one woman who was entitled to vote’ (181). Her subtlety and intelligent discursive manoeuvring may come across as tame or perhaps unexciting and unradical to a post-suffrage audience whose contact with the history of British suffragism has been saturated with the ‘Deeds not Words’ of the militant suffragists.

The collection demonstrates the extent of Fawcett’s interests – ranging from suffrage to child employment to the so-called white slave trade to war and patriotism (where she had much in common with her militant counterparts, the Pankhursts being renowned for their jingoism). Intriguingly, there are also 20 ‘Picturing Fawcett’ inclusions containing photographs and paintings of her, from lecturer to wife to garden party attendee. For those of you who are fans of Pre-Raphaelite art (like me), you may be surprised (like me) to discover that Ford Maddox Brown (1821-93), in his signature style, painted a portrait of Millicent and her husband Henry Fawcett (1872). This was commissioned by their friend, liberal politician Sir Charles Dilke (1843-1911), and such was his affection for the couple, it hung in his home until his death (58-60).

Image Credit: ‘Portrait of Henry and Millicent Fawcett 2ASL/11/02a’, LSE Library. No known copyright restrictions.

In 1918, shortly after the passing of the Representation of the People Act, Fawcett reflected: ‘I most devoutly believe that the Suffrage movement, all through its fifty years’ existence as practical politics, has made continuous and fairly rapid progress’. Admitting there were some disappointments, like the defeat of the Conciliation Bill that would have seen women enfranchised in 1912, she added: ‘those of us whose disposition and training led us to take long views never doubted for a moment that ultimate success was certain […] Looking back over the last fifty years’ work for women, I can truly say it has been a joyful and exhilarating time: punctuated by victory after victory’ (356).

Today, we variously watch on, mobilise, campaign for and protest as women’s rights are won and lost. The ‘Marea Verde’ (‘Green Wave’) movement has recently resulted in the decriminalisation of abortion in places like Argentina and Colombia. However, in 2022, 50 years after the Roe v. Wade judgment (1973) which ruled that the US Constitution protects a pregnant woman’s liberty to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction, the US Supreme Court overturned that historic decision.

In 1918, Fawcett wrote: ‘I can only hope that that those who are beginning their work now may have as joyful a fifty years before them as I and many dearly loved colleagues have to look back upon’ (356). Feminists around the world are still fighting for women’s and gender rights. There is much need among contemporary feminists for inspiration from this book’s evidence of the formidable fortitude, optimism, determination and generous spirit of activists like Millicent Garrett Fawcett. For students and scholars of English social and political life, the broader history of women’s rights globally or even those who simply wish to appreciate the pace of a different time, this book is a must read (and it is accessible as a free open access PDF!).

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.