Across countries in the Global North, the transition to open access to research has in recent years been driven largely through library consortia and national institutions striking transformative agreements with commercial publishers. Drawing on recent work on The University of Sheffield’s content strategy, Peter Barr argues that academic libraries can play a larger role in fostering community-owned scholarly publishing.

This post was originally published on LSE Impact blog.

”‘Lord strike me dead!’’ I says each time,—and I goes out in the air to say it under the open heavens,— ‘‘but wot, if I gets liberty and money, I’ll make that boy a [publisher]!’’ And I done it. Why, look at you, dear boy! Look at these here [sustainable business models] of yourn, fit for a lord! A lord? Ah! You shall show money with [the big 5] for wagers, and beat ’em!”

Magwitch to Pip, Great Expectations, [partially adapted]

It is strange, I grant you, to begin a piece on the budgetary structure of academic libraries with a spoiler warning for a novel of 1861. Nonetheless, here is your warning…

The central revelation in Great Expectations is that the benefactor who has enabled Pip’s rise is Magwitch – the convict he takes pity on in the start of the book. Having won his freedom and fortune in Australia, Magwitch wishes to repay Pip’s kindness. Magwitch cannot enter high society himself, and Pip cannot do so without backing, and so the one provides the funding for the other’s rise. This tale of benefaction was initially told to readers via serialisation. A new form of publishing that sprang up in response to new demands of readership. Indeed, it was serialised in a title owned by Charles Dickens himself. So, if you will accept this contrivance as a starting point, I would like to talk about this interaction between author control, speculative funding and the new forms of publishing required for academia, and specifically why the Library should play Magwitch.

Despite the fact that institutions and funders ultimately provide the money and set the culture within which research is conducted, they have devolved the practicalities of the transition to open research to academic libraries. The assumption being that libraries can leverage their longstanding relationships with academic publishers to negotiate ‘Transformative’ agreements that ensure research is published open access, but these relationships are dysfunctional. In reality, what libraries have proved is that they are skilled at finding the funds to pay for ever-escalating ransom notes, more than they are successful in building equitable partnerships with publishers.

In reality, what libraries have proved is that they are skilled at finding the funds to pay for ever-escalating ransom notes

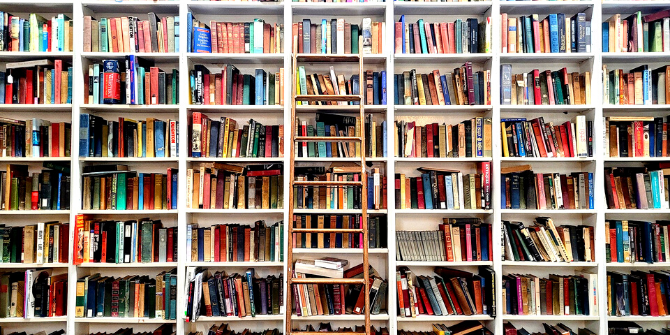

Openly accessible digital content is the natural conclusion of the shift away from print that has been underway for the last 30 years. It is, therefore, the concern of collection managers as much as scholarly communications librarians. The notion of the collection has been turned inside-out, and the concern is for how best to connect researchers with the content they need. The drive for efficiency, facilitated by the scale at which the major commercial publishers operate, has seen a centralisation of library acquisitions. Collections are automated not curated. This has undermined the capacity to think of solutions outside of existing (deeply commercial) structures.

Image Credit: Ray Seven via Unsplash

The major publishers provide a route to Open Access, but they wish to be paid for this service, and they are able to dictate the price. The consequences for poorer institutions, and poorer territories, are obvious. There should be cancellations, and the development of alternative infrastructure, but in the UK this has been avoided by the injection of the UKRI block grant. This maintains income at its historic highs, and allows the existing gentlemen of the big commercial publishers to block the Pips of the scholar-led movement from entering high society.

Institutional libraries are the principal funders of academic publishing, yet the vagaries of the market afford them little control or influence

The ideal is that the dissemination of academic research should be governed by the needs of the research community, not the profit motive. To achieve this, the academic community needs to control their publishing, just like Dickens controlled his. Institutional libraries are the principal funders of academic publishing, yet the vagaries of the market afford them little control or influence. I want to argue for libraries to develop their role as funders beyond merely that of passive consumers. I believe libraries should proactively look to build the transformed, community-owned scholarly communication system, just as they once looked to proactively build their local collections. This, I believe, is the modern function of a library acquisitions budget. To be able to do this, libraries need to put in place three things:

- A statement of intent – at the University of Sheffield our support for this is underpinned by our Comprehensive Content Strategy. Ultimately, libraries are spending delegated budgets on behalf of the university, so without buy-in (or at least acquiescence) to this idea, it is difficult to commit this money without being reined back in.

- Dedicated funding – library budgets remain structured around books and journals, one-off spend and recurrent spend. It is difficult to know where to charge money that is ultimately being used to fund open infrastructure and initiatives that do not directly provide content or services for your users. While it is possible to justify some spending from within existing budgetary categories, to do so at scale requires explicit recognition. At Sheffield we have created the Open Scholarship fund within our library content budget with a recognition that for this to grow we must make savings in what we spend with commercial publishers.

- Robust decision-making – it is necessary to conceive of this activity as part of ‘collection’ building for a responsible academic library. Therefore, it should effectively have an acquisition process. Ideally, one that takes into account the ability of scholar-led publishing initiatives to deliver on outcomes. It is all too easy for unsympathetic university central finance departments to characterise this as a form of charitable giving. It is not; it is strategic spending to achieve a desired outcome (much as Magwitch’s turned out to be on Pip).

It is then for scholars, libraries and community-owned publishers to guard against this alternative infrastructure being subsumed back into the commercial system. We have seen promising players in this area sell out to the major commercial publishers either for the money or for the scale they afford. If this trend continues, there will be no disruption of the status quo. There are some things libraries cannot achieve acting only at arm’s length, only as benefactors. Magwitch could not stop Estella from breaking Pip’s heart. It is not for all libraries to become publishers, but it is for the major research libraries to recognise the power of their content budgets and to reflect that there is something more impressive that can be achieved with this wealth than a read-and-publish deal.

Note: This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, the LSE Impact blog or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.