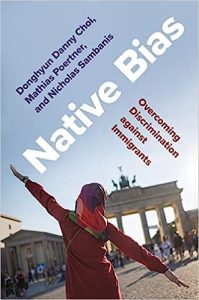

In Native Bias: Overcoming Discrimination Against Immigrants, Donghyun Danny Choi, Mathias Poertner and Nicholas Sambanis present the results of field work experiments conducted in Germany to understand social bias in native populations towards migrant communities. Grappling with a complex social issue, this innovative research suggests that discrimination and bias can be reduced without coercive assimilation that erases the cultural features of migrants, writes Kaelynn Narita.

Native Bias: Overcoming Discrimination Against Immigrants. Donghyun Danny Choi, Mathias Poertner and Nicholas Sambanis. Princeton University Press. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

Literature on migration, borders, and citizenship often discusses bias and discrimination towards immigrant communities. Scholars critique the racialising effect of borders, newspapers report on attacks on migrant communities and activists raise awareness of the violence and exclusion immigrants face. Race, gender and religion are well covered in migration scholarship; what is less discussed are the practical interventions that can be taken to overcome harmful stereotypes and exclusion. In Native Bias: Overcoming Discrimination Against Immigrants, Donghyun Danny Choi, Mathias Poertner, and Nicholas Sambanis apply social identity theory to various fieldwork experiments to suggest methods of overcoming native bias towards immigrant communities. Using the case study of Germany, Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis suggest that their findings can be applied to a broader European context. With the rise of the far right and xenophobic discourse fueling violent anti-immigrant attacks throughout Europe, the research in Native Bias is essential.

Literature on migration, borders, and citizenship often discusses bias and discrimination towards immigrant communities. Scholars critique the racialising effect of borders, newspapers report on attacks on migrant communities and activists raise awareness of the violence and exclusion immigrants face. Race, gender and religion are well covered in migration scholarship; what is less discussed are the practical interventions that can be taken to overcome harmful stereotypes and exclusion. In Native Bias: Overcoming Discrimination Against Immigrants, Donghyun Danny Choi, Mathias Poertner, and Nicholas Sambanis apply social identity theory to various fieldwork experiments to suggest methods of overcoming native bias towards immigrant communities. Using the case study of Germany, Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis suggest that their findings can be applied to a broader European context. With the rise of the far right and xenophobic discourse fueling violent anti-immigrant attacks throughout Europe, the research in Native Bias is essential.

I am wary of flattening social relations – particularly a complex social issue involving bias towards specific communities – to graphs and numerical data, however, the care and detail in the data collection undertaken in Native Bias assuaged my initial hesitations. Native Bias contends that a shared group identity of ‘citizen’ (8) can decrease conflict between immigrant and native communities. Throughout the book, the authors grapple with the salience of group characteristics and deal with the empirically complex-to-capture conception of an individual’s idea of ‘group identity.’ Through their fieldwork activities of staged interventions, they test what group identifiers are the strongest in promoting positive social interactions between native and immigrant communities.

Native Bias contends that a shared group identity of ‘citizen’ can decrease conflict between immigrant and native communities

Some features isolated throughout the book include language, religion and ideology around gender roles. The language isolation contained five components in Chapter Four: a control of a native German, a hijab-wearing woman, and a non-hijab-wearing woman speaking either German or Turkish. The researchers proposed that measuring the bystanders’ willingness to assist the different test subjects when these subjects dropped fruit from their bags could measure how much prominence language skills have in overcoming bias towards migrants.

In popular ‘discourse and culture’ (90), the language skills of migrants are thought to be a ‘critical condition for the acceptance of immigrants into native society’ (91), but Native Bias finds that this statement does not fully capture the influences of social context. They did not find an overwhelming likelihood of a ‘hijab-wearing woman’ speaking German (demonstrating linguistic assimilation) being assisted. This chapter compelled me, as their findings suggest that language does not contribute to the likelihood of prompting assistance from bystanders. Rather than interpreting this pessimistically, the authors argue that ‘the political salience of linguistic difference is moderated by social context’ (110), inferring that exposure to multiple languages and perhaps the policies promoting multiculturalism have succeeded in the German context. This chapter offers a moment of reflection on dominant narratives on the burden on immigrant communities to adopt native languages fully. Moreover, their findings point to the significance of religious identities in immigration bias, and the authors try to locate why bias arises from this cultural marker.

The burden on immigrant communities to adopt native languages fully

The authors’ discussion on religious differences between secular, Christian and Muslim populations explores the stereotypical belief that Muslims hold less progressive views on gender roles. Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis unpack the complicated subject of religious bias, demonstrating the gaps of perception in native populations towards views on gender held by immigrant communities. Drawing from past research, the authors suggest that native people often assume immigrant communities’ gender politics to be aligned with their home countries, namely the Middle Eastern countries listed in the survey. The authors drew on various previously conducted research like the ALLBUS Survey and Muslim Life in Germany. According to the authors, 59.9% of German participants believe that wearing a hijab was not a woman’s choice but reflected regressive views on gender. To test how the performance of ‘shared cultural norms’ can cut through bias, the authors conducted several experiments involving a woman, wearing a hijab or not wearing a hijab, conducting a staged phone conversation expressing either progressive, regressive or neutral sentiments about a woman’s place in the home and broader society. The results show that individuals were more likely to assist a woman wearing a hijab after she expressed a progressive stance on gender roles in German than to assist a veiled woman who had expressed regressive sentiments. In this chapter, the authors aim to illuminate the ‘crosscutting’ nature of how sharing cultural norms can help bridge aspects of religious bias.

Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis unpack the complicated subject of religious bias, demonstrating the gaps of perception in native populations towards views on gender held by immigrant communities

By isolating linguistic and gender identities in social experiments conducted in different areas of Germany, the authors were able to map a commonality between populations that suggests what factors can increase positive social behaviour. What was found to be the most influential in altering the native population’s conception of an immigrant is demonstrating shared cultural norms. Though not entirely pessimistic, the research highlights several difficulties for immigrants. If demonstrating shared cultural norms benefits how the native population perceives an immigrant, where does this leave minoritised populations facing significant barriers to integration due to religious differences? Does this evidence suggest that a significant number of native persons believe immigrants should fully assimilate into society, renouncing features of their culture which do not correlate to the majority population? While Native Bias suggests that adopting similar cultural norms is a powerful bridge to overcome bias in a specific situation, what about persons who are discriminated against or labelled as part of an ‘immigrant community’ due to physical appearance or because they have been accused of engaging in anti-social behaviour? What pressure does this place on groups new to a country?

These questions are not a criticism of the original and creative empirical research conducted by the authors, but rather an illustration of the thought-provoking work of Native Bias and the complexity of the challenges it explores. The authors aim to offer policymakers practical solutions, like promoting mandatory cultural classes for immigrant communities and developing policies that allow native populations to have continuous positive interactions with immigrant communities. The authors’ research shows that the enforcement and adherence to salient group norms has the power to overcome bias. What is difficult is developing policies which target the correct group norms but do not promote a coercive form of assimilation. One step the authors suggest would be working to promote the ingroups to humanise the ‘outgroup’ through ‘perspective taking” and ‘personal story-telling ’(204) to promote empathy and understanding between natives and immigration communities.

A need for more research to thoughtfully consider social contexts and perceptions around intersectional identity that can contribute to policy strategies to increase the acceptance of immigrant communities

Overcoming deep-seated legacies of bias to build social cohesion is an enormous challenge, and sweeping revolutionary change, while ideal, is unlikely. The research presented in Native Bias suggests that gradual progress is being made and offers ways to make impactful changes now. Their work demonstrates a need for more research to thoughtfully consider social contexts and perceptions around intersectional identity that can contribute to policy strategies to increase the acceptance of immigrant communities within societies.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Main Image Credit: Rasande Tyskar on Flickr.