Politics of Representation: The British Empire’s Photographic Obsession: by Suyin Haynes

“BREAK THE INTERNET KIM KARDASHIAN” was emblazoned in capital white letters across the front of PAPER magazine’s Winter 2014 issue. And break it she arguably did. Fashion photographer Jean-Paul Goude’s images of the reality television star clad (and unclad) in a skin tight black leather dress, pouring champagne into a glass delicately placed on her rear, caused a global meltdown on social media. Yet while Kim K’s image was plastered all across the web, it also provoked criticism and a resurgent interest in the 19th century South African woman Sarah Baartman, an unexpected consequence that Goude probably wasn’t anticipating.

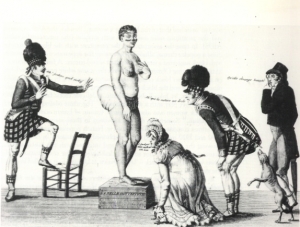

Baartman was part of the Khoikhoi tribe in South Africa, a region that changed hands between different European rulers throughout the 19th century. She was brought to Europe to be made a scientific and entertainment spectacle, because of her unusual physique, attributed to what we now know today as the condition of steatopygia, an accumulation of fat around the buttocks and thighs. Cartoonists of the day created caricatures of Victorian gentlemen voyeuristically peering through their telescopes to focus on her buttocks and breasts, and the PAPER images of Kardashian drew criticism for its similarities to the exploitation and fetishisation of the female body.

Photography as a Tool of British Imperialism

American essayist Susan Sontag tells us that photography “implied the capture of the largest number of subjects. Painting never had so imperial a scope”. If we look back to the early days of the British Empire, we can see that this imperialistic nature of photography was indeed used to capture the image of people around the world. It was responsible for preserving and propagating stereotypes that reinforced the British Empire’s perspective of superiority over its colonial subjects. Just as Baartman was paraded around Europe in the early-mid 1800s by white men who called her “the Hottentot Venus”, the exposure of black bodies to the unsolicited European male gaze was replicated through the creation and dissemination of the photographic medium later in the century.

1884 marked the Berlin Conference, and the carving up of the African Continent by greedy European Empires not content with equal portions of a land that was not even theirs to divide. Yet Victorian Britain seized this opportunity to build upon the new age of science and discovery, particularly following the introduction of the Kodak box camera in 1889. Exciting developments in photography increased its accessibility to many amateurs; a small portable camera and roll film meant that anyone could take a photograph simply by pressing a button. Thus, ‘photographing the native’ to permanently cement their image constituted an important part of the colonial encounter circa 1880-1910. British anthropologists, explorers, military officers and government agents were all charged with the task of capturing the image of ‘darkest Africa’ and presenting this image to the British population, the majority of whom would never experience the realities of colonialism abroad for themselves.

The ‘Hottentot Venus’ and the ‘Angel of the Hearth’

The potency of photography for imperial use reinforced the ‘alien’ stereotypes that were propagated by scientists of the period to project the sense of British superiority. As gender theorist Anne McClintock has argued, the African woman was seen as an object of desire in an exotic land, sexualised on her very difference to the clean, pure, virginal and Christian archetypal Victorian ‘Angel of the Hearth’. Based on my survey of photographic examples from across South Africa, Nigeria and Ghana, local women were systematically subjected to the uninvited gaze of the camera wielded by upper-class, British men. When this forced interaction was carried out in the name of science, it was justified as anthropological exploration with a focus on the body. There are clear, challenging examples of focus and fixation on specific body parts with the exclusion of facial features, from the archives at the Royal Anthropological Institute and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. In the most extreme form of dehumanization and de-individualization of the African colonial woman, she is photographed without her face but simply her breasts, reminiscent of the exposure of Sarah Baartman.

‘Peculiarity’ assigned to anatomy in this way illustrates the sexual, violent gaze automatically imposed upon the black woman, and the immediate association of her character with her genitalia, breasts or buttocks – cases of steatopygia were featured prominently in anthropometric photography. Further ‘pathologization’ of African women in terms of their body was also evidenced through attitudes towards scarification, tattooing or body marking practices. Photographic treatment in this respect marked attempts to highlight the ‘brutality’ and ‘savagery’ in localized treatments of the body within a supposedly scientific framework.

The Appropriate Response, from the Appropriate Artists

In 1892, John Thomson of the Royal Geographic Society commented that photography provided “a means of handing down a record of what we are, and what we have achieved in this nineteenth century of our progress”. His claim embodies the cultural arrogance of imperial Britain’s ability to make and record history, which was ultimately reflected in the circulation of imperial photography that shaped late Victorian thinking about ‘the dark continent’. As contemporary feminist bell hooks has argued, the ability to make the ‘Other’ view themselves through an imperialistic Western lens has always been characteristic of imperial and even post-colonial relations; control over images continues to be “central to the maintenance of any system of racial domination”.

Art historian Barbara Thompson notes that historically for African women, “their own bodies have served as the primary means for self-expression and self-representation, whether through clothing, personal adornment, coiffure, body scarification or painting”. Clearly then, for the African woman, her body is a site of celebration, experience and identity. It is the male Victorian photographer in these examples who bears responsibility for distorting those positive connotations of the body into a site of primitivism, curiosity and shame.

While Goude’s image of Kardashian is perhaps an insensitive, superficial glossing over the pain endured by its referential figure of Sarah Baartman, we can instead look to more positive responses influenced by the image of the colonized black woman from African artists working in the postcolonial context. Reclamation of these images by artists such as Wangechi Mutu, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle and Angele Essamba are much more inspiring ways of looking at self-representation of the black female body in the photographic arena.

Within the historical field, there is a severe lack of engagement with these types of histories. They have been effectively written out of history by the voices that have to oppress and dominate. Engagement with these sources can be an emotionally challenging task, and maybe this has contributed to reluctance to explore these issues. It is incredibly difficult not to feel anger at some of the dehumanizing photographic practices that coalesced with the very worst of British colonial rule; but it is essential that we take a much more nuanced view than simply looking at photographic sources as ‘the oppression of the black woman’. Looking to the work of empowered African female photographers fractures the West’s ‘monopoly on seeing’, and gives the appropriate attention and respect to women such as Sarah Baartman and her contemporaries that they deserve.

Editor’s note

This blog was kindly written and contributed by LSE International Relations and History graduate Suyin Haynes in preparation for the forthcoming publishing of her full dissertation with the UPR. I would like to thank Suyin for her contribution.