The student voice on technology, wellbeing and society.

This blog post is one of a series on phase two of LSE 2020, a student-focused project that has engaged with 440 students in 2017. It is written by Emma Wilson, Graduate Intern for LTI. You can find her on Twitter (@MindfulEm).

In this post, we discuss an issue that was frequently brought up by students: the impact of technology on society and our emotional wellbeing in an era of ever-increasing interconnectivity. The issues raised provide context into how today’s students navigate the digital age. This will, undoubtedly, have an impact on student expectations about the teaching and learning experience. It also highlights some of the challenges that need to be addressed if we are to support the mental health and wellbeing of our students.

Digital capability includes self-care, and that self-care requires a critical awareness of how digital technologies act on us and sometimes against us. (Beetham, 2016)

Students raised concerns about the impact of technology on our mental wellbeing and our ability to form and maintain relationships. They spoke about digital identity, and how our online activity influences a person’s place in society.

Concern for student mental health has been of increasing importance in recent years. A 2016 YouGov survey of Britain’s students found that 27% reported having a mental health problem, with 63% feeling they had levels of stress significant enough to interfere with daily life. There is the fear that technology (especially social networking and the need for instant gratification) may impact an adolescent’s neurobiology and exacerbate symptoms of stress, anxiety and social isolation. [1][2]

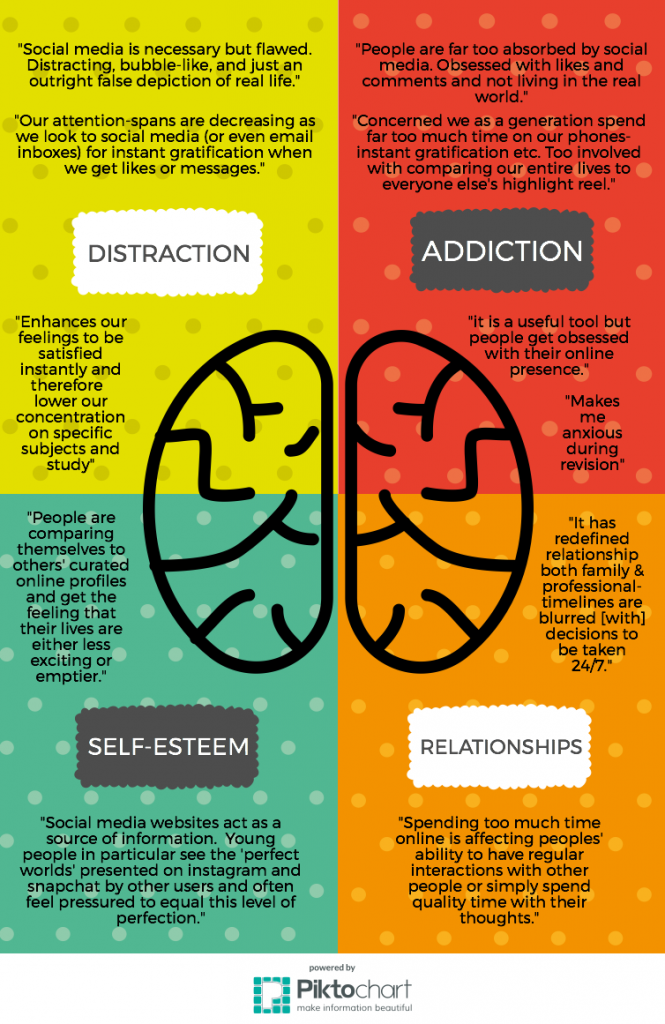

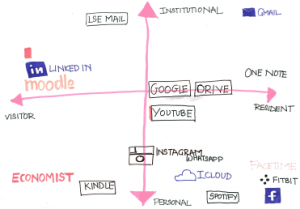

In both the face-to-face interviews and the online survey carried out for LSE 2020, students frequently raised concerns about the impact that technology can have in other areas of life. These concerns have been represented in an infographic and divided into four areas:

- Addiction to our devices and social media

- Distraction and instant gratification

- The distortion of reality and sense of self, and its impact on our self-esteem

- The social impact and the changing nature of our relationships

Firstly, students have raised concerns about the impact of technology on our attention spans. With the temptation of constant distraction – from Facebook to checking our phones – this poses the risk that traditional ways of teaching and learning might prove more challenging for today’s student. Given these concerns, it may be more appropriate to use diverse methods to cater for learning preferences. For example, changing the format of a two-hour lecture by interspersing it with interactive elements such as group exercises, short videos or encouraging audience participation.

It is also important to consider the mental health impact from social media and online communication. Whilst students spoke of a world that is becoming more integrated, they were also aware about the distorted reality of a person’s online persona. Despite this self-awareness, it was felt that students were struggling to manage the amount of time spent online.

This highlights the importance of continuing to fund and run wellbeing weeks and self-management course for students, such as those previously conducted by Student Wellbeing Services or the Student Union. The mental wellbeing of students will undoubtedly impact performance and overall satisfaction of the LSE experience.

Finally, students raised concerns about the impact that virtual communication might have upon our face-to-face communication skills.

‘…some people are substituting online interaction for real life meetings’

‘Generally social media has had a detrimental effect on our social lives by increasing social anxiety and limiting real human contact’

Such concerns emphasise the importance of including face-to-face interaction and interactivity during lectures, seminars and group projects. It may also partly explain why students frequently commented on the value they ascribe to discussion and debate within their course. Whilst the online world has become an integral part of the student journey, students are concerned about its social implications and do not want to see the total replacement of human interaction at university.

Moving forward, there is a growing importance for equipping students with the tools needed to manage their wellbeing in the 21st century. This could be facilitated through a whole-university approach between teachers, staff, Student Unions and student wellbeing services.

The mental wellbeing of students will undoubtedly impact performance and overall satisfaction of the LSE experience. We need to work together to ensure that tomorrow’s student is well-equipped for the rigour of higher education.

References

[1] ANDERSON, J. & RAINIE, L. 2012. Millennials will benefit and suffer due to their hyperconnected lives. Pew Internet and American Life Project.

[2] GIEDD, J. N. 2012. The Digital Revolution and Adolescent Brain Evolution. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 101-105.

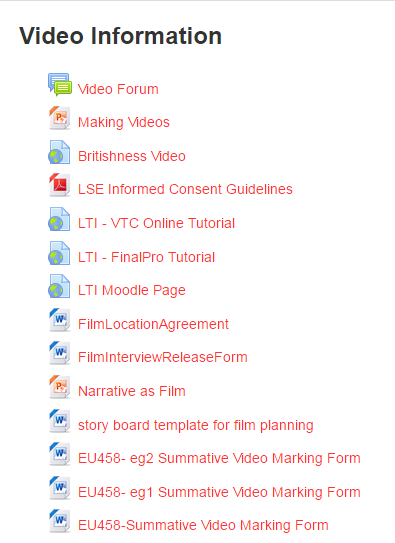

As part of the Urban Policy and Planning course, students produce written work alongside a group presentation and a short interpretive film of neighbourhood fieldwork. Film-making started two years ago with students using their own devices. Last year they were helped by an LSE alumnus who is now a filmmaker to better understand the process of storytelling and how to use the equipment. This year, Nancy applied for DSLR kits to improve the quality of the work produced. An evening screening of the 8 short films produced by the project groups was also organised at the LSE, at the end of which a panel of ethnographers and filmmakers judged the films and awarded three prizes: Best Overall Film, Best Cinematography and Judges Choice.

As part of the Urban Policy and Planning course, students produce written work alongside a group presentation and a short interpretive film of neighbourhood fieldwork. Film-making started two years ago with students using their own devices. Last year they were helped by an LSE alumnus who is now a filmmaker to better understand the process of storytelling and how to use the equipment. This year, Nancy applied for DSLR kits to improve the quality of the work produced. An evening screening of the 8 short films produced by the project groups was also organised at the LSE, at the end of which a panel of ethnographers and filmmakers judged the films and awarded three prizes: Best Overall Film, Best Cinematography and Judges Choice.

As highlighted in the description of the project, video production was gradually introduced in the Geography course. Students received the help from a professional filmmaker and were able to familiarise themselves with the equipment during a trip to Manchester in the first part of the year.

As highlighted in the description of the project, video production was gradually introduced in the Geography course. Students received the help from a professional filmmaker and were able to familiarise themselves with the equipment during a trip to Manchester in the first part of the year. In the spring of 2015 I finished my first year of American grad school. Coming from the German university system I knew it was going to be a Protestant re-education camp in terms of work load and ethic. By the end of that spring I had to write three sizeable papers in short succession and ‘time is of the essence’ took on a new meaning. Lucky for me some of my friends had just started using this writing set-up that streamlines all the things that take no brain but lots of time: citations, the bibliography, and worrying about the different format of citations when in footnotes vs. when in the bibliography.

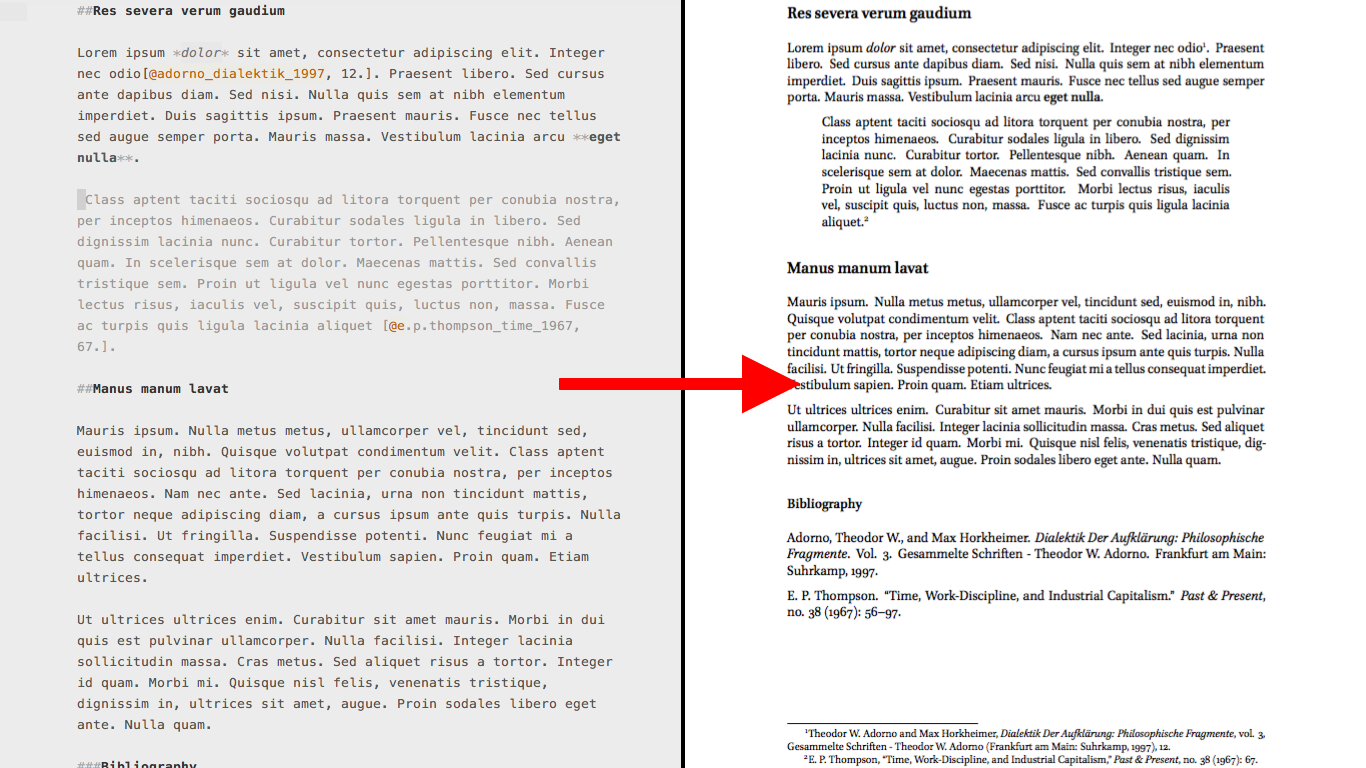

In the spring of 2015 I finished my first year of American grad school. Coming from the German university system I knew it was going to be a Protestant re-education camp in terms of work load and ethic. By the end of that spring I had to write three sizeable papers in short succession and ‘time is of the essence’ took on a new meaning. Lucky for me some of my friends had just started using this writing set-up that streamlines all the things that take no brain but lots of time: citations, the bibliography, and worrying about the different format of citations when in footnotes vs. when in the bibliography.