There are an estimated 2.8 million ‘gig workers’ in the UK, according to the Fairwork Foundation, doing work that is mediated via digital platforms or apps: this includes driving for Uber, riding for Deliveroo, cleaning via Helpling or getting contract work via Upwork. In this post, Kelle Howson, Mark Graham and Srujana Katta of the Fairwork Foundation (based at the Oxford Internet Institute) share insights from their work looking into whether and how the UK’s election parties account for and treat digital platform (or gig economy) workers – and thus how Britain’s political parties are preparing (or not) for the future of work.

There are an estimated 2.8 million ‘gig workers’ in the UK, according to the Fairwork Foundation, doing work that is mediated via digital platforms or apps: this includes driving for Uber, riding for Deliveroo, cleaning via Helpling or getting contract work via Upwork. In this post, Kelle Howson, Mark Graham and Srujana Katta of the Fairwork Foundation (based at the Oxford Internet Institute) share insights from their work looking into whether and how the UK’s election parties account for and treat digital platform (or gig economy) workers – and thus how Britain’s political parties are preparing (or not) for the future of work.

Many forms of work in the UK are becoming more flexible, more independent, more insecure, and more harmful. But how is this understood and acknowledged by the politicians who both represent us and drive policy in this area? As the UK’s political parties have scrambled in recent weeks to release coherent policy platforms, we at the Fairwork Foundation have combed through the main party manifestos for acknowledgement of the rapidly changing nature of work and plans to curb the most destructive impacts of the gig economy.

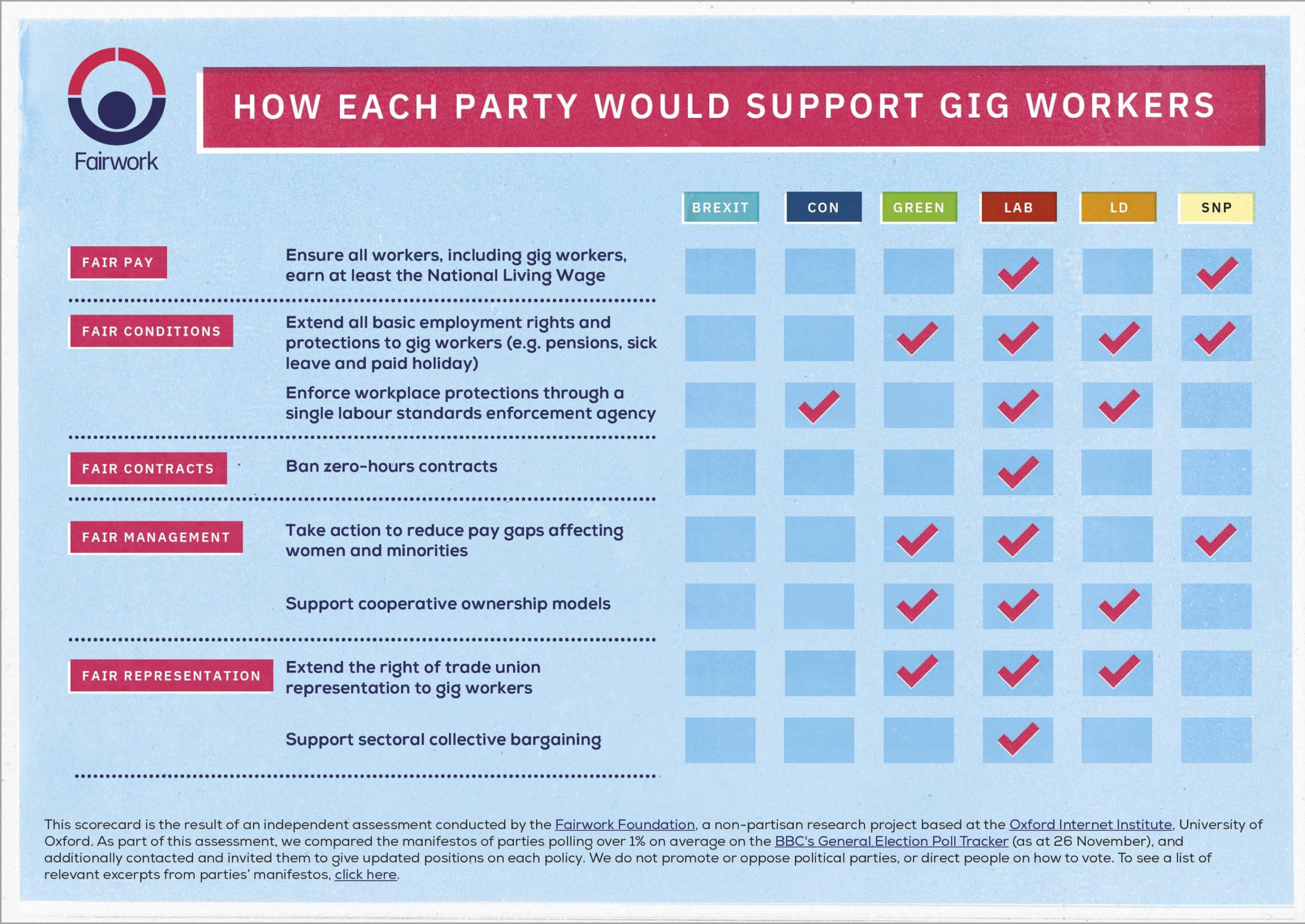

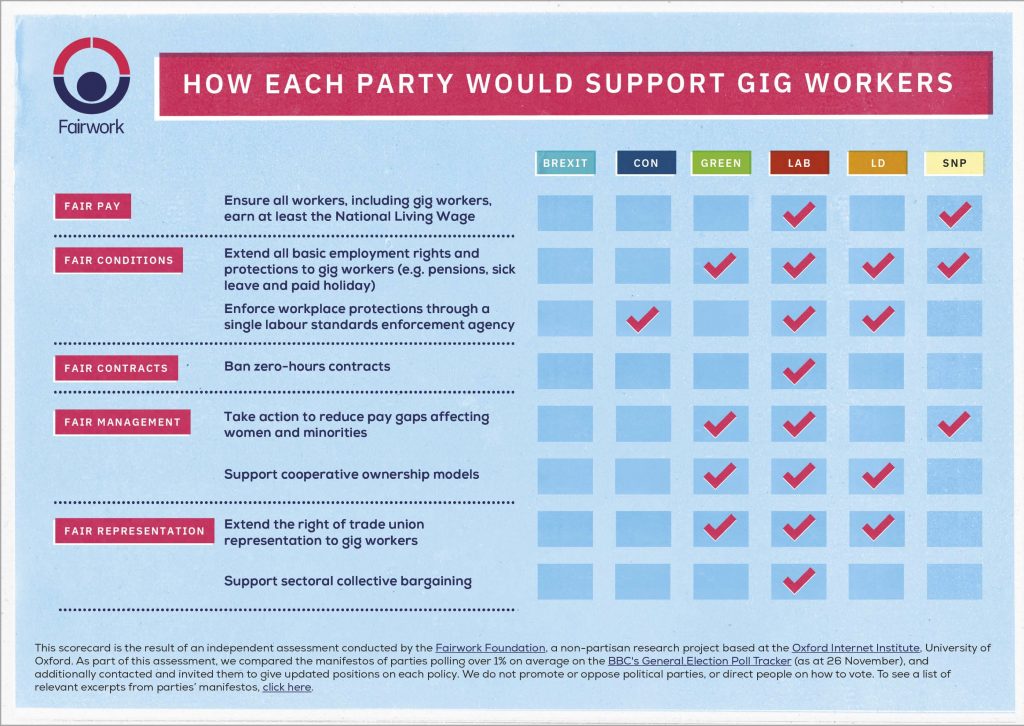

We produced a ‘manifesto scorecard’ that compares commitments that the major parties have made in the realm of gig workers’ rights. We assessed their policies against the core principles of fair work that our research has shown makes the greatest difference to those drivers, cleaners, carers and couriers striving for a decent living at the margins of the digital labour market. While the election run-up has been dominated by the ongoing question of Brexit, we need to remember that for these precarious workers, this election provides a critical and urgent opportunity for change.

The reality of gig work often falls far short of its promises. Due to the unregulated nature of the gig economy, the attractive promise of flexibility is experienced instead as either an undersupply of jobs, or pressure to work incredibly long hours for inadequate pay. The promise of objective management is undermined when the threat of deactivation from a platform without due process is a constant looming threat. The promise of independence is often revealed as hollow, as workers become fully reliant on a platform to keep a roof over their head.

But policymakers already have tools at their disposal to promote those aspects of gig work that workers value while ensuring that they enjoy decent working conditions and secure livelihoods. The extension of workplace protections to gig workers is within reach, and would make an immediate difference to millions of families in the UK. Such protections, highlighted in our manifesto scorecard, would include ensuring that gig workers earn a national living wage; banning exploitative zero-hours contracts; making it harder for companies to offload risk onto workers by misclassifying them as independent contractors; and guaranteeing gig workers the right to union representation.

We based our scores on the concrete, explicit commitments that have appeared in party manifestos. We also reached out to each party to request their input. We were somewhat surprised by the significant variation in attention paid by parties to this issue. While some parties (notably Labour, Greens and the Liberal Democrats) offer considered and innovative solutions, others (e.g. the Tories and the Brexit party) have little to nothing to say about the future of work. In many cases we encountered vague rhetoric, ambiguous statements and frequent contradictions.

All of the major parties at least give a nod to gig workers in their manifestos. For example, the Tories pledge to ‘protect’ gig workers—albeit offering little information about how they would actually go about doing so aside from enforcing current labour law and giving workers the ability to ‘request a more predictable contract’ (Conservative Party Manifesto 2019:39). In a previous policy document, the Greens committed to banning zero-hours contracts, but that same commitment is absent from their manifesto, which prevented us from awarding them that point.

In their manifestos, Labour, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats all clearly stated that they would support collective ownership models, extend all basic employment protections to gig workers (which the SNP will also do), and guarantee the right to trade union representation. Labour and the SNP commit to enshrining a living wage into law. Only Labour commits to banning zero-hours contracts.

Digital platform work can and should be rewarding and secure. Innovative work platforms can expand access to work opportunities, facilitate direct and mutually beneficial transactions between service providers and consumers, and promote productive, connected and sustainable economies that benefit all. However, the hundreds of interviews conducted by our team with gig workers around the world have indicated that this is seldom the case in practice.

We do not need to accept insecurity as the price of flexibility. Nor should we convince ourselves that it is a necessary or inevitable step on the road towards security. Providing a route into earning, especially for people who tend to be marginalised from more conventional forms of work, is one important function of the gig economy.

After we released our manifesto scorecard last week and circulated it around workers’ networks, we were disappointed to see many workers asserting that instituting the policies in the scorecard would destroy the gig economy.

The idea that we must accept precarity and casualisation as the natural price of flexibility is seemingly already deeply entrenched in our imagining of the gig economy. However, we would argue that the fact that gig work is usually experienced as insecure, precarious and unsafe is not natural or inevitable. It is a political choice—or rather stems from an absence of political will.

This election provides an opportunity to articulate and shape the way we want to work in the future. With a third of all labour transactions predicted to be mediated by the gig economy by 2025, now is the time to for policymakers to ensure that the gig economy develops in a way that does not further entrench inequalities.

This article represents the views of the authors, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.