As a third of the world’s population remain in lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the new coronavirus, Kanika Jain, a writer and communications professional based in Mumbai and a former student in LSE’s Media and Communications Department, discusses the displays of ‘solidarity’ demanded by the Indian government that could end up endangering the lives of citizens.

As a third of the world’s population remain in lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the new coronavirus, Kanika Jain, a writer and communications professional based in Mumbai and a former student in LSE’s Media and Communications Department, discusses the displays of ‘solidarity’ demanded by the Indian government that could end up endangering the lives of citizens.

India is currently almost four weeks into what was meant to be a 21-day lockdown. Prime minister Narendra Modi gave the country four hours’ notice when he announced the lockdown at 8pm on 24 March. Thousands of migrant workers, stranded in cities with no jobs and no transport, began a long walk back home that stretched hundreds of kilometres. In hospitals, medical professionals struggled to continue their duties without the necessary protective equipment. Reports of infection at a religious gathering in a mosque exacerbated a dangerously Islamophobic socio-political environment, never mind that the event was held over a week before the lockdown commenced.

On 22 March, despite the threat of COVID-19 forcing the country into shutdown, thousands of Indians had flooded the streets in defiance of the imposed janata curfew, banging pots and pans in solidarity with their Prime Minister. When Modi announced a 9 minute power-off candlelight vigil on the 5 April, the nation obeyed even though power operators across the country feared its impact on the electricity grid. In both instances, images of togetherness and #GoCoronaGo flooded news channels and social media. In both instances, healthcare workers – the supposed beneficiaries of this show of solidarity – were ignored when they demanded better protective gear and increased testing. What then, was the point of these spectacles?

Spectacles are not meant to fight COVID-19 or implement welfare policies. Spectacles are media events designed for broadcast on television as a nation building exercise. In times of social isolation, a reinforcement of national identity can act as social glue and a temporary relief to loneliness. As we stand on our balconies and watch hundreds of homes light up with candles and flashlights, we can’t help but feel part of something bigger than us (maybe a Coldplay concert?). And just like a concert, Modi’s tasks have an entertainment value, to provide a distraction to a bored public. They are simply another addition to the nationalist rhetoric for consolidating Modi’s image as a supreme leader, one whose followers jump at every chance to obey his orders.

Such an ardent display of deference causes more problems. If the prime minister wanted a show, he got one, without all the necessary precautions. Rather than respect the norms of social isolation and stay indoors, people paraded down streets and set off fireworks. In Telangana, a member of parliament representing the ruling party BJP led a protest march against the pandemic with the slogan ‘Chinese virus go back’. Off the streets, WhatsApp buzzed with messages that proclaimed the defeat of COVID-19 through the divine and numerological implications of the prime minister’s command. Not only does such fake news belie a dangerous lack of awareness about the current pandemic, it also further proves that Modi’s followers will stop at nothing to deify their leader. Instead of a show of support, this defiance of science and social distancing was a mockery of the efforts of healthcare professionals who are already battling eviction, low pay and a lack of personal protective equipment. Performance for the sake of performativity is a meaningless distraction at best. In times of a pandemic it is a call for disaster.

But more than anything, spectacles are about illusion. Nothing could be a better illusion of solidarity in an increasingly divided nation, where the pandemic has reinforced the gap between the haves and the have-nots, where even a virus can be used as a tool for communalisation. It is the illusion of action on part of a complacent central government whose lazy policy making and lack of planning has brought the country to the brink of socioeconomic disaster. And it is the illusion of good citizenship on part of the public, who rather than demand accountability from their government, is happy banging plates and lighting candles. Illusion is no stranger to a society rife with fake news. The spectacle is political, but its depoliticised garb allows it to be normalised. Events such as these are the real life version of the WhatsApp forwards on family group chats. They may be a display of unity, but it is a unity based on the exclusion of minorities and the marginalised, as well as anyone else who does not preach the politics of those in power.

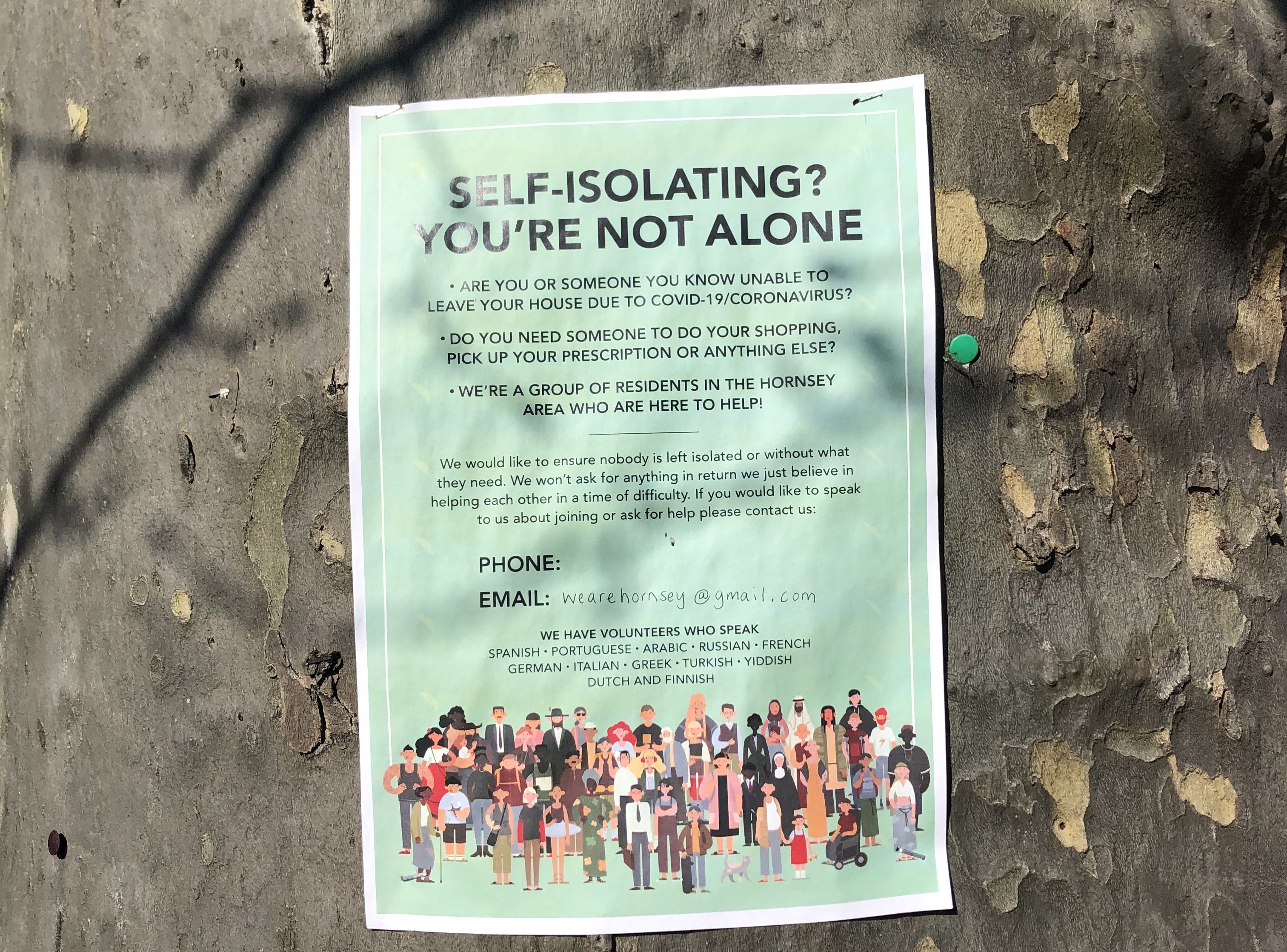

There’s nothing wrong with a bit of spectacle, and narratives of solidarity have never been more important than at a time of isolation and fragmentation. The problem is when spectacle becomes a priority at the cost of policymaking. The central government has already proven its ability to conjure media events that capture the national imagination. What we need now is strong relief measures that follow suit and deliver.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Mercedes Bosquet on Unsplash