As several European countries start to ease restrictions put into place to stop the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the UK is preparing to announce its next steps later this week. Lee Edwards, Associate Professor and Programme Director for the MSc Strategic Communications in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE, discusses the UK government’s response to the crisis and some of the questions that we still need to address.

As several European countries start to ease restrictions put into place to stop the spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the UK is preparing to announce its next steps later this week. Lee Edwards, Associate Professor and Programme Director for the MSc Strategic Communications in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE, discusses the UK government’s response to the crisis and some of the questions that we still need to address.

The COVID-19 pandemic, in all its horrific reality, is a multi-faceted crisis for governments across the world. But alongside the well-documented public health and economic consequences, other challenges are also emerging that address much deeper issues of who we are, both as individuals and as a society.

Many of the questions that arise reflect a deep tension between collective and individual interests. To what extent do we balance institutional surveillance in the name of public health, with our right to privacy and defence against exploitation? How do we balance the rights of vulnerable people to self-determination with the desire to preserve life? If lockdown is a crucial strategy for collective survival, how do we justify it to families facing violence and fear in their own homes, or whose livelihoods have disappeared in a puff of smoke since March 23 and are facing destitution?

Thus far, in the UK at least, government officials have explained their decisions with only implicit reference to these kinds of questions. Thus, lockdown is essential, but resources are provided (food parcels, an emergency phone line, additional shelters) for those who are vulnerable or scared. However, as political philosopher Michael Sandel argues, questions of the collective good are ethical and philosophical as much as practical, and the definition of the collective good is always subject to change. The longer-term balance of collective versus individual interests will not be settled through food parcels and shelters.

In neoliberal, market-driven economies, individual self-interest is prioritised over collective welfare. This is not to say that collective interests are not relevant, but they are generally regarded as an outcome of effective market operations and rational individual decisions. Market-based thinking has saturated so many areas of our lives that we find it difficult to conceive of other logics that might drive policymaking. Indeed, neoliberalism’s failure to provide a basis for defining the collective good is reflected in its absence from government narratives justifying lockdown and its apparent success. In the UK, the strategy has been justified, even celebrated, using vacuous tropes that conjure up nation and victory (the ‘British People’, ‘our NHS’, ‘We’ll meet again’) but do not relate to the reality of the fragmented, deeply unequal society that is Britain today.

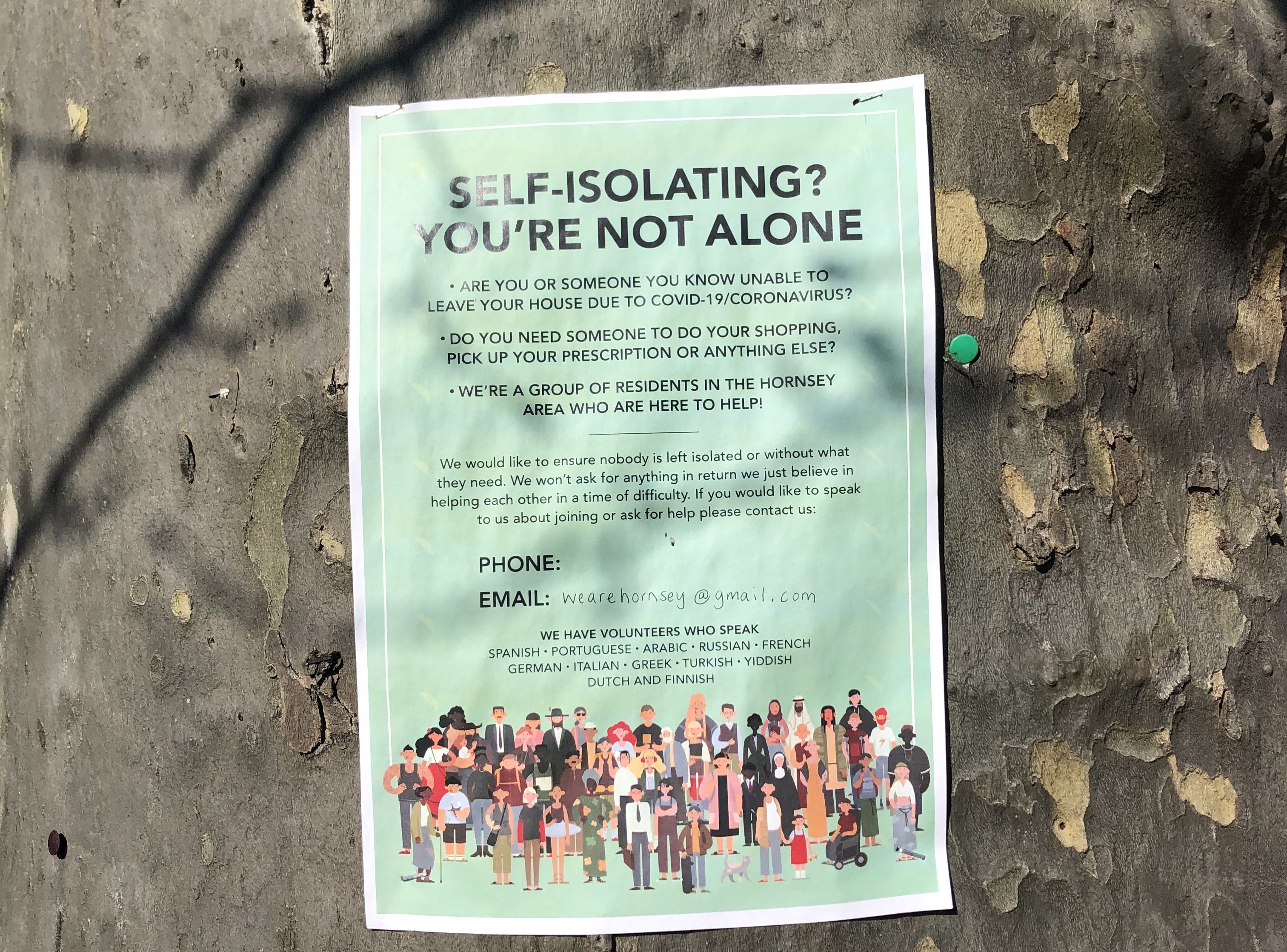

As former Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf argued during a recent LSE event, we need ‘engaged and exemplary leadership’ in a crisis. It must deliver guidance about actions to take, as well as the capacity for a coordinated response at all levels of the community, from grass roots, neighbourhood initiatives to government committees. But beyond this, leaders cannot succeed unless they communicate effectively. In a crisis like this, effective communication certainly requires clear messages and information about changes to policy and practice as events unfold. But, as Sirleaf argued, it also requires honesty and respect for the audience. Ignoring difficult questions about decision-making processes, the decisions made, and their consequences, is more likely to communicate instability and misdirection than strong leadership. Equally, assuming that the public will simply accept policy decisions that reference assumptions about our collective and individual lives, which we have neither discussed nor agreed upon, is a mistake.

In the UK, some public consultations about the crisis have taken place. The education, tourism, and energy industries, for example, have been the focus of emergency consultations about how to address the impact of COVID-19 and recovery from the crisis. Media outlets are demanding answers and explanations for policy choices, and many people are calling for greater transparency about crucial decision-making fora such as the Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies. A petition has been launched for a public inquiry into the handling of the crisis. Yet even if all these demands are met, identifying whether or not policy was appropriate, or decisions well-made, depends on having agreement on what we think the common good should be, how it should be balanced against individual interests and, correspondingly, what principles should be guiding our actions.

Government cannot determine the answer to these questions without engaging the public. Politicians work on our behalf, but they are rarely representative of the full gamut of experiences that should underpin a robust discussion about values. Wider consultation is essential. Moreover, whatever forms of engagement are initiated, they should be based on deliberative principles that can help to ensure the democratic quality of the process. They need to be inclusive, equitable, accountable and deliver a sufficiently wide range of evidence to effectively inform policy-making. In the end, the ‘British People’ whom the Prime Minister so readily invokes, need to be given a voice. Citizens, not politicians, need to decide what balance to strike between individual and collective interests, so that today’s choices have some legitimacy in the longer term.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.