Online political advertising has seen an unprecedented amount of attention in the run up to recent elections as online campaigning, often via social media, becomes an increasingly significant part of political parties’ strategies. Concerns over how precisely ads are targeted at specific categories of voters are now common around the world, and various governments have been looking at how to bring regulation of online political advertising in line with regulation in the offline world. Here, University of Amsterdam researchers Carolina Menezes-Cwajg, Paddy Leerssen and Jef Ausloos provide insight into the findings of a new report which maps the efforts to improve transparency in targeted political advertising in a range of countries.

Online political advertising has seen an unprecedented amount of attention in the run up to recent elections as online campaigning, often via social media, becomes an increasingly significant part of political parties’ strategies. Concerns over how precisely ads are targeted at specific categories of voters are now common around the world, and various governments have been looking at how to bring regulation of online political advertising in line with regulation in the offline world. Here, University of Amsterdam researchers Carolina Menezes-Cwajg, Paddy Leerssen and Jef Ausloos provide insight into the findings of a new report which maps the efforts to improve transparency in targeted political advertising in a range of countries.

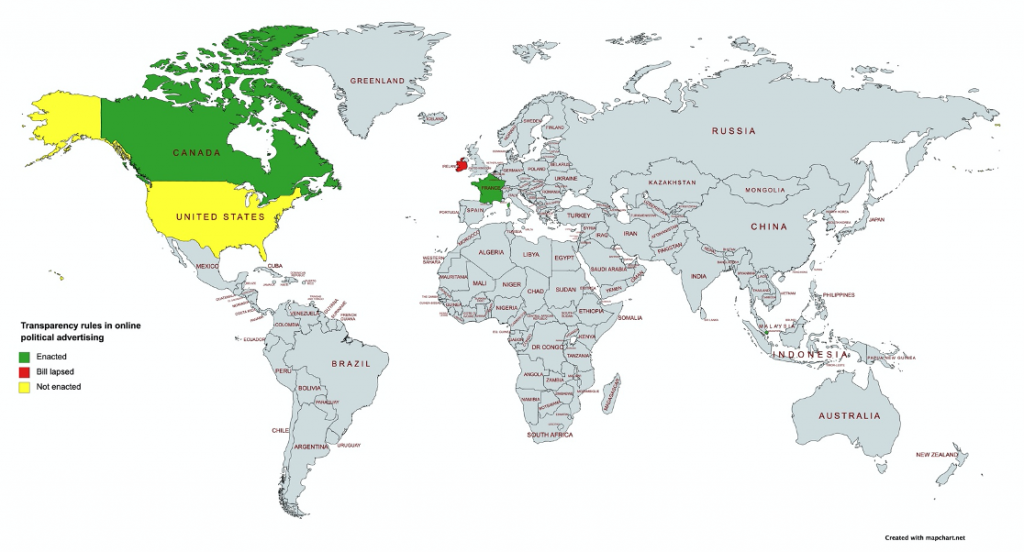

Recent years have seen an explosion of government proposals to regulate political microtargeting. From Canada to Singapore, governments are trying to end to the regulatory vacuum in this space. In particular, many of these initiatives aim to increase the transparency of political targeting. At present, political microtargeting practices are shrouded in secrecy, with little information available as to the actors, funds, messages, and targeting techniques involved. Transparency is accordingly seen as a key condition for democratic control over these practices, without which further accountability may be difficult if not impossible. Our new report, Transparency Rules in Online Political Advertising: Mapping Global Law and Policy, offers a first attempt to map this new wave of online transparency rules.

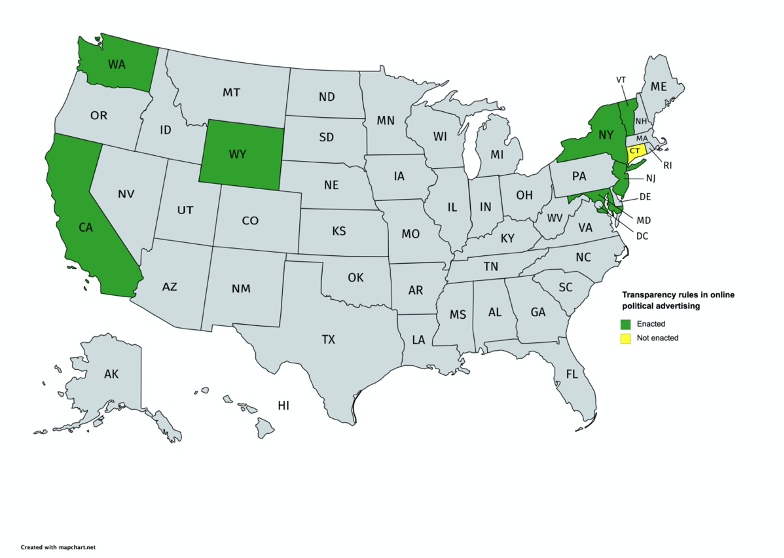

The report focuses on online transparency initiatives aimed at advertising platforms within the context of elections. The first section begins with a geographical overview, showing where and what initiatives were proposed and enacted, examining the work being done in Canada, France, Ireland, Singapore and the United States. Each initiative is discussed in terms of disclosure content (what information must be disclosed?), scope of application (by whom and under what conditions?), and format (how must the information be disclosed?). The second section of the Report then zooms in on the United States, where state-level legislators have been particularly active in drafting a wealth of new proposals.

The devil is in the detail (or lack thereof)

The Report reveals a lot of legislative activity in the United States and Canada. Notably, legislation in these countries tends to be the most detailed, compared to other jurisdictions. The US Honest Ads Act, for instance, clarifies that disclosure notices must state ‘the name of the person who paid for the communication’ and ‘provide means for the recipient of the communication to obtain the remainder of the information required’, and ‘with minimal effort and without receiving or viewing any additional material other than such required information’. As a comparison, Singapore’s Code of Practice for Transparency of Online Political Advertisement only states that disclosure notices must contain ‘the name of the individual or organization who paid for the ad’ and be ‘easily accessible’. Whereas the Singaporean Code merely requires notices to be ‘easily accessible’, the US law requires that the disclosure notice be displayed in a ‘clear and conspicuous manner’ and defines what that would mean in legislative terms.

The Honest Ads Act further explains that the ‘clear and conspicuous manner’ requirement is satisfied in different ways depending on the type of communication. For instance, if the statement is in ‘text or graphic’, then it must ‘appear in letters at least as large as the majority of the text in the communication’ and must be ‘contained in a printed box set apart from the other contents of the communication; and be printed with a reasonable degree of color contrast between the background and the printed statement’.

Even amongst jurisdictions with very detailed laws, there are noticeable differences with respect to content and form requirements. Washington’s State Legislature amendments merely state that records must be displayed in a format that is ‘open for public inspection during normal business hours during the campaign’, whereas the California DISCLOSE Act requires records be made ‘available for online public inspection’ in ‘machine-readable format’ and describes how these records must be given access to. Records must be displayed either through a ‘prominent button, icon, tab or hyperlink’ with the text ‘View Ads’ or text of a similar wording. The law then further specifies where these must be located in the online platform to ensure greater visibility for the public.

It will be interesting to see how these varying levels of detail will affect transparency in practice, especially considering the multinational dimension of most of these platforms. Other experiences in platform regulation warn that platforms can subvert the effective enjoyment of user rights by means of their interface design. For instance, the design of Facebook’s mandatory complaint form under Germany’s Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (or ‘NetzDG’) in effect undermined the impact of this law by making it harder for users to access. Similarly, online services continue to find new and creative ways of optimising their cookie consent notices and nudge users towards their preferred outcomes. Will general transparency rules for political microtargeting lead to similar struggles? Will open norms like ‘accessibility’ or ‘visibility’ suffice, or are more detailed specifications needed?

Let’s talk politics

Another interesting finding from the mapping exercise was the wealth of state-level initiatives in the US, reflecting the mounting political pressure to regulate online political advertising. In total, nine initiatives spanning eight states were found and reviewed. Another interesting discovery was that at state-level, most proposals were already enacted as law, which stands in sharp contrast with the movement at a national level in the US, where none of three pending bills (Filter Bubble Transparency Act, Honest Ads Act and Voter Privacy Act) has been passed. This reflects the lack of meaningful bipartisan cooperation within the US federal legislator, and the current federal administration’s disinterest in regulating political microtargeting. Whether these existing national level bills will become laws remains to be seen. Much depends, it would seem, on the upcoming elections in November.

A light at the end of the tunnel?

The move to regulate political microtargeting is still very much in its infancy. Most jurisdictions across the world have no relevant policy to speak of. From the most detailed proposals we identified at national level, only the Canadian Elections Modernization Act was enacted.

Further research is sorely needed into these new laws. How will online services comply with these transparency rules? And how, if it all, will this transparency actually affect users and societies? A critical approach is necessary to ensure that transparency rules are implemented effectively, and, crucially, do not come to displace more direct regulation on issues like election funding and personal targeting. We hope that our report offers a starting point for further international and comparative research, analysis and debate in this new field of regulation.

This article gives the views of the authors, and does not represent the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.