Maria Rikitianskaia, Visiting Fellow at the LSE, and Gabriele Balbi, Associate Professor in Media Studies at USI Università della Svizzera italiana (Switzerland), delve into the history of radio and find that the omnipresence of radio in the media technological world, even today, is phenomenal but often underrated. In this post, they argue that radio is synonymous with technological innovation.

Maria Rikitianskaia, Visiting Fellow at the LSE, and Gabriele Balbi, Associate Professor in Media Studies at USI Università della Svizzera italiana (Switzerland), delve into the history of radio and find that the omnipresence of radio in the media technological world, even today, is phenomenal but often underrated. In this post, they argue that radio is synonymous with technological innovation.

Every epoch gives us new keywords. In 2020, not surprisingly, according to Merriam Webster, the most used word was “pandemic”. In the realm of technologies, the past decades have given rise to many new words associated with digitalisation. There are the endless prefixes: such as e-, i- and smart-, as well as completely new concepts: wireless, digital revolution and, more recently, digital transformation. Whilst most words live to define a year, a decade or a century at most, one has an unexpectedly long, pioneering history: the radio.

The omnipresence of radio in the media technological world was, and still is, phenomenal. Today, radio is mostly associated with broadcasting. However, our recent research into the radio history of the 20th century demonstrated there were numerous technologies known under “radio”.

The radio waves have entangled us quite literally, mediating our everyday communication practices, thus creating what we called “the mediatization of the air”. In other words, these technologies and realms of radio have mutually shaped each other. But, surprisingly, broadcasting has been able to obfuscate all the others and to monopolize the radio history.

Here are five technologies of the 20th century whose kinship to the big family of ‘radio’ is far from obvious today:

Radiography

The radio has more than literally ‘penetrated’ the history of the 20th century, exposing both our minds and bodies to radio waves. Radio as mass medium and as a medical tool were not as distinct as they are today. Wilhelm Roentgen and Nikola Tesla, two of the most known pioneers in the history of radio transmissions, exchanged some opinions on wireless radiation. The first president of the Radio Society of London (now the Royal Society of Great Britain) Alan Archibald Campbell-Swinton, apart from being an adamant opponent of the monopoly of the UK public-owned British Broadcasting Corporation, was known as a pioneer of medical radiography. The demarcation across radio, wireless, broadcasting and radiography was more ambiguous than it may seem today.

Radio detection and ranging (mostly known as radar) and satellites

It may seem surprising, but the radar also comes from a “radio” family. Just as radio broadcasting station, radar radiates message from one point to several others. Moreover, early radars were actually called radios, such as Radio Set SCR series, an automatic-tracking microwave radar developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Radiation Laboratory during the Second World War on the basis of the British experiments in the radio navigation.

Another technology close to radar is satellite. Both have been used as tools to explore space with radio waves and as technologies of control and surveillance (and thus used by armies and navies). The first satellite networks for commercial use were built in the 1960s, especially to transmit TV (and radio) programmes and telecommunication messages. The radiation from space today determines most of our communication practices and allows arriving on time in the right place by using GPS, which itself is a form of ‘radio navigation’.

Source: Decoding Wireless Project, courtesy of The Guglielmo Marconi Foundation and Museum, Pontecchio Marconi, Italy.

Radiotelegraphy

Experimented on in the late 19th century, radiotelegraphy with wireless messages in Morse code became a profitable business in the 20th century. Guglielmo Marconi in Italy, Alexander Popov in Russia, Adolf Slaby in Germany, Eugene Turpain in France, Oliver Lodge in the United Kingdom and many others in several countries have been regarded as inventors of radio, despite the fact that they were key figures in the history of radiotelegraphy, not broadcasting.

Radiotelegraphy in Morse code, and later, radiotelephony with sound and speech transmission, was actually closer to the mobile phone of today than the broadcasting of mass medium. In 1919, Marc Raboy explains, Marconi imagined radiotelephony as ‘[p]ocket wireless telephones by means of which a passenger flying in an aeroplane over France or Italy might “ring up” a friend walking about the street of London with a receiver in his pocket […]’. In fact, this vision of technology was even ‘smarter’ than today’s phones, since you could phone on a plane.

Radiomobile

Prior to the mobile phone, there was the radiotelephone. Throughout the 20th century, the radiotelephone evolved into several forms of point-to-point mobile radios used by police officers or firefighters before the Second World War (a kind of walkie-talkie), by taxi drivers (the so-called radio taxi) or by truck drivers in the 1970s and the 1980s (the Citizens Band radio, known as CB). When the early forms of mobile telephony emerged in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, they had a direct link with radio; the Italian, French or English radiomobile kept the word radio in their names because communications were brought through radio connections. Early mobile telephone networks, often referred to as cellular telephone networks, functioned and still function due to the radio towers (so-called cell towers) that allow customers to connect on the move.

Packet radio networks

The idea of the packet radio network is simple – sending packets of data via radio communication. The most successful example of packet radio networks is the Wi-Fi. Wi-Fi networks developed outside the scope of the licensed radio spectrum, and continue to evolve today in the ‘grey area’ of international regulations, causing a kind of ‘radio revolution’. This very successful standard of the wireless networking today shapes most of our wireless connectivity.

Declining popularity

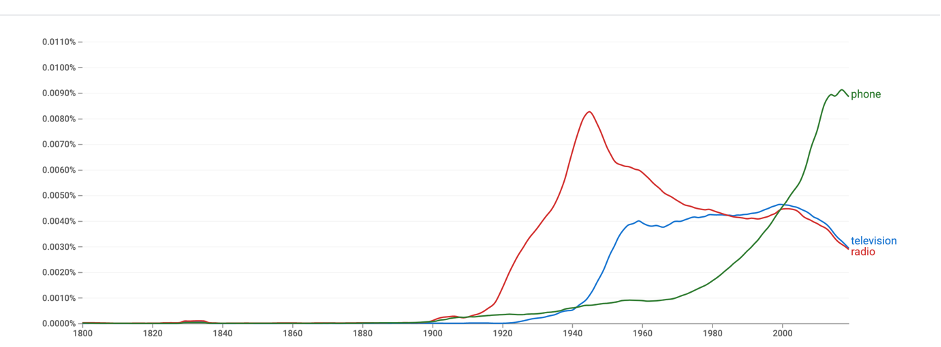

Whilst the word “radio” is still used today, it is no longer on the as popular as it was in the 20th century. Why? There can be several reasons. Gradually, each of successful “radio” technologies dropped “radio” in its name to make itself distinguishable. Also, and especially with the Cold War, radio slowly started to be linked to radiation and so to be connoted as a dangerous technology, especially after catastrophic accidents, such as Chernobyl. Then, radio gradually became synonymous with “old” media, and thus was not seen any more as radical and innovative. Finally, other key words emerged in the realm of communication over time: for example, this graph shows how the frequencies of the words “radio” and “television” declined in the recent years, giving way to “phone” from the 2000s.

Keywords are byproducts of the society inventing and imposing them. Over time, they emerge, decline and maybe re-emerge. Clearly, radio was one of these keywords in the 20th century and its popularity was due to being a flexible term. Far more than just broadcasting, radio was for long time synonym for technological innovation.

This article represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Thank you very much for this expansive article. Regarding radar and radio sciences more generally, you might find this interesting re the little known contribution of foundational Australian scientific work on radar and radio sciences in first half of 20th century. This is a brief memoir only relating the work of a key figure in this research who also happened to be my great uncle: https://www.science.org.au/fellowship/fellows/biographical-memoirs-1/john-percival-vissing-madsen-1879-1969