The lockdowns implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic have had profound effects on many areas of society. Paul Jacobsen and Professor Dr Norbert Kersting of the Department of Political Science at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster write here about their study on young people’s political participation during the lockdown in Germany which found that in order to sustain online political participation, it needs to be linked to offline elements.

The lockdowns implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic have had profound effects on many areas of society. Paul Jacobsen and Professor Dr Norbert Kersting of the Department of Political Science at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster write here about their study on young people’s political participation during the lockdown in Germany which found that in order to sustain online political participation, it needs to be linked to offline elements.

Broad political participation is regarded by many as the ‘lifeblood of democracy‘. It strengthens the legitimacy and stability of democratic regimes, and functions as a bridge between the people and their elected representatives. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic forced an abrupt halt of social and public life, many aspects of local political participation in Germany, as elsewhere, have been impeded:

- Registration of political parties and candidates for local election became a cumbersome task, especially for small parties which often withdrew from elections. This led to extensive executive dominance and a huge advantage for incumbents.

- Campaigning has predominantly been organized on digital channels, which also advantaged bigger political parties and wealthier candidates.

- German local councils and committees continued to be held, but the new participatory instruments, implemented since the 1990s and focusing on consultative deliberative democracy, completely stopped.

This lockdown of key aspects of democratic engagement in response to the pandemic reinforced processes of digitalization and became a stress test for the existing digital political infrastructure. In terms of participatory democracy, this gives rise to a new discussion over the future of online participation and whether it should be organized around the concept of blended participation in a hybrid mix of online and offline instruments (see Figure 1 for a selection of different offline and online instruments).

Our study, which focused on the immediate consequences of the lockdown on young people’s online political participation, confirmed that successful and sustainable online participation needs to be linked to offline participatory instruments. After a preliminary novelty effect at the beginning of the German lockdown, online participation did not significantly increase, which we posit is because it because it could not be organized within a framework of blended participation that would have encompassed the strategic combination and sequencing of online and offline participatory instruments.

Examples of online and offline participation

There are four key spheres of political participation: representative democracy (e.g., participating in elections), direct democracy (most commonly associated with referendums), deliberative participation (e.g., open forums or citizen assemblies) and demonstrative participation (e.g., protesting, or online newspaper comments).

The ‘participatory rhombus’ shown below can be used to classify actions and instruments between the poles of ‘invented’ and ‘invited’ space. Participatory instruments from the invited space are planned top-down by state institutions, strongly regulated and secured in the constitution. On the other hand, invented space is developed bottom-up by the citizens and is exposed to less formalization and regulation.

Figure 1: Participatory Rhombus

Digital Youth Participation in Germany

As Kersting argues elsewhere, broad youth participation is regarded as a vital contributor for today’s and tomorrow’s political challenges, and different studies have shown that adolescents are already relatively strongly committed to both digital and analogue political participation.

However, the style of young people’s participation differs significantly from that of older generations. Studies have shown that young people prefer thematic, time-limited, project-oriented engagement. They also favor dialogical and discursive participatory instruments, and increasingly detach from conventional forms of representative democracy and only very occasionally engage in a long-term commitment with parties. Rather, they engage in demonstrative forms of participation (e.g., the Fridays-for-Future protests since 2018) and are increasingly involved in social and economic engagement like boycotts and crowdfunding.

The usual offline participation channels of young people have been blocked by the government’s COVID-19 containment policies, in particular the prominent mass demonstration Fridays for Future. Subsequently, young people tried out new forms of pandemic-appropriate public offline protests, as well as digital platforms to channel their protests. In general, there were great hopes attached to online youth participatory mechanisms in Germany, which were expected to experience a catalyzing function through the pandemic. Young citizens seemed well set up with the resources for online participation: in 2020, 99% of all households in Germany with 12-19-year-olds had a wireless internet access and 94% of the adolescents possessed their own smartphone. Evidence suggests that practically all adolescents are online, several days a week: in 2020, they spent an average of 258 minutes per day online. The internet has evolved to a ubiquitous tool of young people.

Online tools during the pandemic

The present study compared the traffic on the online youth participation app PLACEm before and during the lockdown. PLACEm is a German participation app that invites young people to participate in their environment. It is designed to be used by municipalities or local institutions to promote participation of young people and to innovate politics. The app provides a platform on which various participation suppliers (e.g., youth clubs, youth centers, youth parliaments, schools, the voluntary youth fire brigade, sport clubs, etc.) can create their own places, invite their members and organize their participation online. These so-called places are the core of the app: within places, information can be shared, members can be questioned, polls and quizzes can be created, and ideas can be submitted.

The present study compared the traffic on the online youth participation app PLACEm before and during the lockdown. PLACEm is a German participation app that invites young people to participate in their environment. It is designed to be used by municipalities or local institutions to promote participation of young people and to innovate politics. The app provides a platform on which various participation suppliers (e.g., youth clubs, youth centers, youth parliaments, schools, the voluntary youth fire brigade, sport clubs, etc.) can create their own places, invite their members and organize their participation online. These so-called places are the core of the app: within places, information can be shared, members can be questioned, polls and quizzes can be created, and ideas can be submitted.

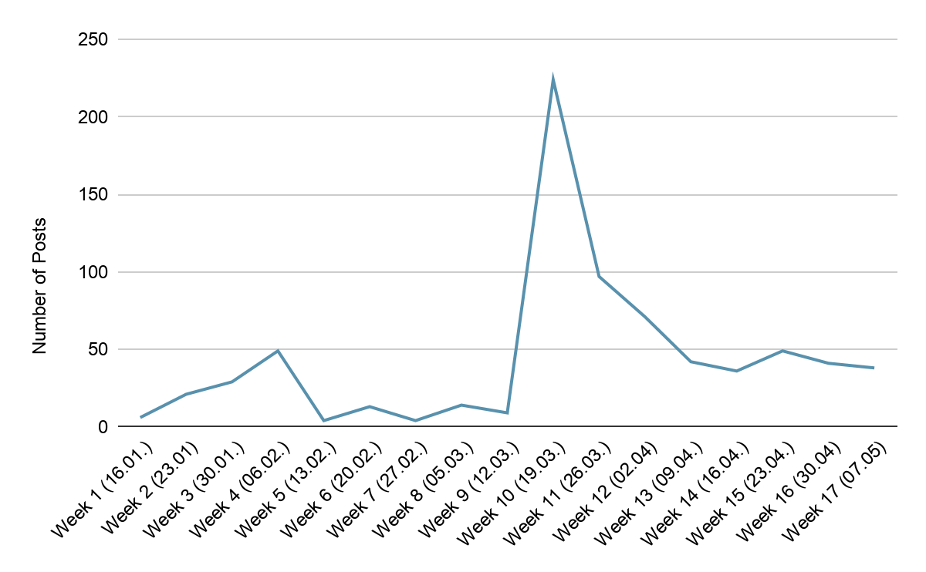

The study found that the lockdown triggered a sharp increase (353.28%) in traffic to the participation tools. Most of the increase was concentrated in the first two weeks of the lockdown (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Overview of the Weekly Number of Administrator-Issued Posts on PLACEm, 2020

Youth facilities were better able to increase their presence and activity on online participation tools, whereas schools generally failed to switch over to online tools. In contrast with pre-lockdown conditions, participatory platforms were predominantly used for information provision during the lockdown.

The study results indicate that the lockdown triggered a novelty effect rather than leading to a long-term utilization of online participatory instruments. Even innovative formats like PLACEm with its gamification mechanisms could not bind its users in the long run without a link to offline participatory instruments. The forced digitalization impeded the establishment of blended participation by the complete halt of offline participatory activities. Other trends in Germany create additional barriers for online youth participation. This includes general reservations regarding digitalization due to security and data protection concerns, deficiencies in the digital infrastructure and a lack of engagement for youth participation – Germany is one of the least developed countries in Europe regarding digital infrastructure and digitalized politics and administration.

Our study makes clear that the rise of online participation through the pandemic should not be interpreted as a foregone conclusion The study shows the importance of blended participation to guarantee sustainable long-term participation (see the Direct and Deliberative Democracy (DDD) Project for the choice and sequencing of participatory instruments). Government, the municipalities and the various youth organizations should make sensible investments in institutional support and extensive efforts regarding the implementation and monitoring of online participatory instruments, and thereby enable authorities to not only cushion breakdowns in participation like the current one, but to make use of the promising potential of online youth participation for future involvement as well.

This article gives the views of the author and does not represent the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.