The combination of war discourse, scientific technocracy and opaque algorithmic technologies is making it difficult for dissenting and marginalised voices to speak up in times of pandemic. In this post, PhD researchers Sebastián Lehuedé (LSE), Kirill Filimonov (Uppsala University) and Kat Higgins (LSE) wonder whose voices will count in the world to come. This is an extract of an article originally published in Progressive International in September 2020.

The combination of war discourse, scientific technocracy and opaque algorithmic technologies is making it difficult for dissenting and marginalised voices to speak up in times of pandemic. In this post, PhD researchers Sebastián Lehuedé (LSE), Kirill Filimonov (Uppsala University) and Kat Higgins (LSE) wonder whose voices will count in the world to come. This is an extract of an article originally published in Progressive International in September 2020.

COVID-19 is ‘a portal, a gateway between one world and the next’, wrote Indian author Arundhati Roy at the beginning of the lockdown period in April. But what kind of world is on the way, and whose voices will count in the making of it? In our view, only a programme of radical democratisation—one that creates space for dissenting voices and redistributes volume to marginalised groups—will guide us through this portal to a new, better normal. Otherwise, we risk the continuity, and even reinforcement, of the existing racial, class, religious, gendered and sexual asymmetries in a post-pandemic world.

Unfortunately, the democratic arrangements that have taken shape since the arrival of the pandemic have served to deepen the democratic deficit rather than fill it. In particular, we explain here how the deployment of war discourse, technocratic forms of governance and opaque algorithmic technologies is setting up what we call the COVID-19 democratic deficit.

Language of War: Obscuring Inequalities and Bracketing Off Dissent

In the early days of the UK coronavirus lockdown, Prime Minister Boris Johnson described the pandemic as “a fight [in which] we can be in no doubt that each and every one of us is directly enlisted”. Johnson was not the only world leader to cloak this global crisis of public health in the language of war and militarism, with similar discourses operating in India, Russia, France and the United States.

Certainly, there is a sense of urgency and exceptionalism that comes pre-packaged with language of national security which may have helped lay the groundwork for widespread acceptance of emergency lockdown measures. However, much like the ‘War on Terror’ and the ‘War on Drugs,’ the War on COVID-19 conjures a vision of society under threat that relies for its coherence on multiple forms of omission: in particular, the omission of many lives from public grief, and of many emerging political concerns from serious democratic deliberation. The disproportionate infection and mortality of Black people, refugees and precarious low-income workers has made clear that vulnerability to the virus is uneven, and that the conditions of this vulnerability – poverty, systemic racism and neoliberal capitalism among them – long pre-date the virus itself. However, wars tend to be imagined and memorialised as temporary exceptions to everyday politics, rather than extensions of it. When we use the language of war to narrate the pandemic, we rationalise urgent action on the basis of novelty and put pressure on our capacity to recognize and narrate political continuities. Those who have attempted to foreground these continuities in the public sphere, such as Black Lives Matter protestors, have found themselves accused of politicising an unprecedented crisis of public health – the implication being, of course, that the harm wrought by the virus has no precedent in politics.

War discourse conjures a vision of the (usually national) social body as a singular unit, with all subjects threatened by the same sinister force and all wanting the same self-evident interventions for their protection. However, the disproportionate impact of expanded policed powers on Black communities, of school closures on women, and of work-from-home instructions on those in precarious and casualised work, to name just a few examples, confirm that the struggle to survive the pandemic is not singular. While (some of) these measures have been essential to minimizing mortality rates, framing them in the language of national security makes it hard to discuss their uneven, inequality-entrenching effects and harder still to mitigate those effects with thoughtful public policy. Meaningful democracy finds itself under pressure in a wartime vision of pandemic citizenship, which imagines the citizen only as ‘life’ in need of urgent and self-evident forms of protection from death. With little time or space in public discourse to recognize and engage with diverse and competing needs among citizens, politics risks becoming a closed field of forgone conclusions.

Technocracy: The Expert Apparatus versus Ordinary Citizens

One of the key political dichotomies of the past few years has been that between populism and science: juxtaposed with the supposedly irrational and erratic populist politics was respectable and cold-blooded expertise. Yet, with the emergence of COVID-19, the privileged position of expertise over politics has proved detrimental to an inclusive and democratic response to the pandemic.

Sweden’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis is a primary case in point. Here, almost 6,000 lives have been lost to the virus; in May, Sweden topped the global ranks of highest coronavirus deaths per capita. Sweden’s system is characterised by a bureaucratically organised governance, where significant decision-making power rests in the hands of unelected officials. In the case of COVID-19 crisis, the response was orchestrated by the national Public Health Agency. Sweden’s democratically elected government has preferred to avoid direct accountability and emphasised its reliance on recommendations issued by the bureaucratic establishment. This was all the more surprising given that these recommendations have often contradicted those of the World Health Organisation – suggesting, for instance, that wearing masks in public does not fit Sweden’s coronavirus strategy. Furthermore, the public has never been presented with models sufficiently explaining the laissez-faire approach. The agency also gravely underestimated the risks of the virus and miscalculated the efficiency of the chosen strategy.

Sweden’s case is characteristic of political participation in the age of COVID-19. Despite Germany’s relatively successful handling of the crisis, similar patterns of depoliticization were also seen there. Popular discontent with the technocratic response to the crisis formed part of the basis for protest movements in countries as distant and disparate as the US, India, and Russia. The ridicule of the protesters’ message in mainstream media (that went as far as to call them covidiots) missed the key point: those citizens were speaking out, often desperately, against their own powerlessness in the face of intensifying economic hardship and inadequate state support.

The Swedish case reveals that unaccountable experts can both make profound miscalculations and dodge responsibility. Treating scientific expertise uncritically would do (and has historically done) a profound disservice to democratic citizenship. The key question is how we can delicately overcome this democratic deficit in a way where scientific knowledge would be supported by spaces where citizens can have a say on the decisions that dramatically shape their daily lives.

Algorithmic Technologies: Exclusion by Design

A third and final mechanism related to the democratic deficit has to do with the prominent role that data, algorithms and mobile apps have had in the discussion. Despite their contribution to the response to the crisis, in many cases the implementation of these technologies have narrowed down the possibility for dissent.

The way that governments and the media have approached data and algorithms, marked by an unquestioning faith in numbers, runs the risk of excluding vast segments of the population since it has not been accompanied by more profound questions over the built-in exclusions of the datasets and their visualisation. In addition to this, there has been little attention to the extent to which ordinary citizens and journalists can understand and contest these data. The use of opaque algorithms by governments is equally worrying since in some cases they are not subject to public scrutiny, as the case of the Solidarity Income in Colombia illustrates. Social media platforms are one of the few places where citizens can go in order to express their dissent. However, attempts to control these spaces, such as the ‘ciberpatrullaje’ in Argentina, are adding to the existing state and corporate mass surveillance.

In most cases the apps and technical infrastructures that have become fundamental over the last months respond to the interests of powerful transnational companies. These companies are taking advantage of the current situation in order to gain control of services that were previously provided by the state, which is the rationale behind Apple and Google’s seemingly generous offer to develop tracing apps for free. This form of concealed privatisation leaves societies further away from the ideal of democratic control of key areas of social life and implies that some states have succumbed to the lobby of companies with monopolistic and anti-competitive ethos.

Information technologies have not had a neutral role in the pandemic. As of today, the quantification of the debate, the seizing of the state by big tech companies, and the use of obscure data and algorithmic technologies are fundamental elements of the democratic deficit.

The road ahead

Will the pandemic engender a new form of communism or a new mode of exercising sovereignty? The answers to these questions are still open, but we do know that only a radical and inclusive type of democracy will make it possible to counter elites’ attempts to narrow down the field of what is subject to discussion. If the pandemic is a portal into a new world, there are reasons to believe that this new world is being shaped by the powerful.

However, there are also reasons to be optimistic. The pandemic has laid bare that people are willing to stand up even under the harshest conditions, of which the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, digital protests in Russia, and ‘common pots’ in Chile are but a few examples. In our view, only a radical type of democracy, especially sensitive to the voices of marginalised communities and dissenting groups, would make it possible for these initiatives to flourish and acquire centrality in the public debate, rather than remain portrayed as exceptions.

This article represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

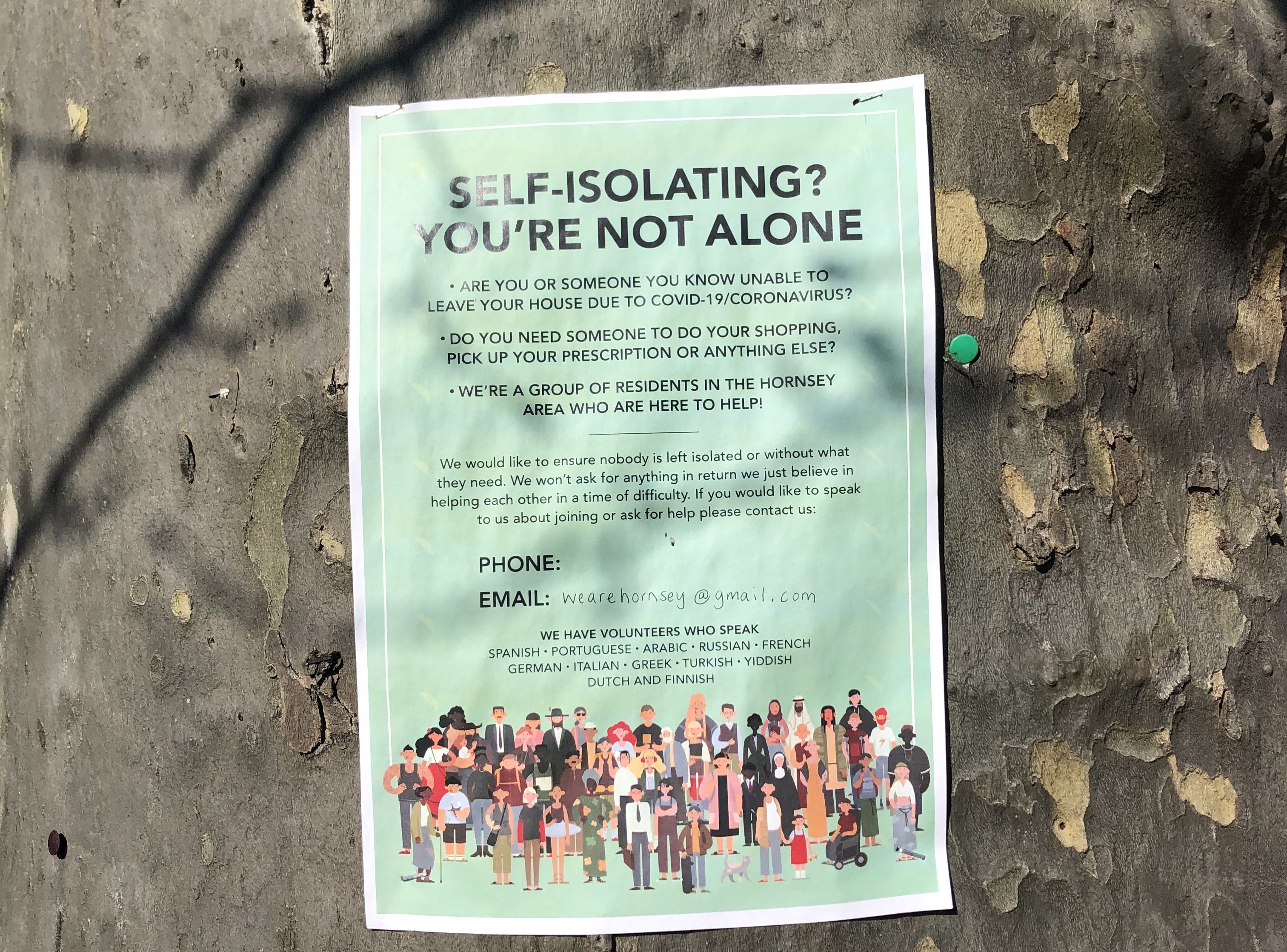

Featured image: Photo by Grooveland Designs on Unsplash