In intensive ethnographic fieldwork, LSE’s Afroditi Koulaxi and Maria-Christina Vogkli travelled to the Thessaly region in north-eastern Greece to record the experiences of citizens internally displaced due to Storm Daniel, a severe weather phenomenon that hit this area in September 2023. Here, the two researchers discuss the ecology of communication and its digital inequalities as manifested at this juncture of climate change and migration.

In intensive ethnographic fieldwork, LSE’s Afroditi Koulaxi and Maria-Christina Vogkli travelled to the Thessaly region in north-eastern Greece to record the experiences of citizens internally displaced due to Storm Daniel, a severe weather phenomenon that hit this area in September 2023. Here, the two researchers discuss the ecology of communication and its digital inequalities as manifested at this juncture of climate change and migration.

Storm Daniel in context

Storm Daniel – the Mediterranean tropical-like storm that hit Greece on 4 September 2023 – left thousands of Greek citizens residing in the Thessaly region homeless and propertyless. With a population of 688,255, Thessaly stands as a microcosm of the broader challenges posed by climate-driven displacement. Most of the those we encountered in the area were over the age of 60 from low social and educational backgrounds with some of our participants fully illiterate, heavily relying on agriculture and distanced from main urban centres.

Storm Daniel, characterised by unprecedented levels of precipitation, wreaked havoc across Thessaly, inundating communities, crippling infrastructure, and claiming 18 lives in its wake. The magnitude of the storm’s impact is reflected in staggering statistics such as more than 10,000 calls to emergency services, thousands of households left without electricity, and extensive damage to buildings, roads, schools, and critical infrastructure.

Not only has the devastating aftermath of Storm Daniel highlighted the urgent need for effective crisis management and support for displaced communities, it has also underscored the minimal (and almost absent) role of digital technologies in environmental migration in the region.

This post explores how the disparity in access to digital technologies and the internet has emerged as a critical barrier to recovery and support.

How do Thessalian climate refugees navigate and address digital inequalities to manage displacement?

An effective response to such crises involves understanding and leveraging the three dimensions of the ecology of communication: hyperlocal networks, gatekeeper dynamics, and information poverty.

Hyperlocal networks: a pivotal element in addressing digital inequalities is the strategic enhancement of networks of self-organising micro-structures at the level of the neighbourhood – especially given the state of abandonment and the fact that citizens mainly possessed analogue mobile phones or relied primarily on landlines during and in the aftermath of the Storm.

The Collective Soup Kitchen (see Figure 2) in Farkadona represents a vital physical space within the hyperlocal network of the Thessaly region. This self-organised and solidarity-based informal group emerged as a beacon of hope and support from flood victims for flood victims. The Kitchen serves “not just as a place for distributing essential food supplies,” one of the key organisers said. “The Kitchen is collective. We cook together. We share what we cook. We are not a catering service or providing food. Our philosophy is that we are not alone, that we are a team, and this is what we try to achieve through the Kitchen.”

The phrase “Only the people feed the people,” inscribed on the lids of most food containers suggests that in times of crisis and in the complete absence of the state, it is the collective effort and support of the community that ensures a sense of belonging. Such messages highlight the gap between institutional promises and the actual support received and further reinforce the valuable and essential role this community plays in filling the gaps resulting from formal state deficiencies and responding to the needs of vulnerable citizens.

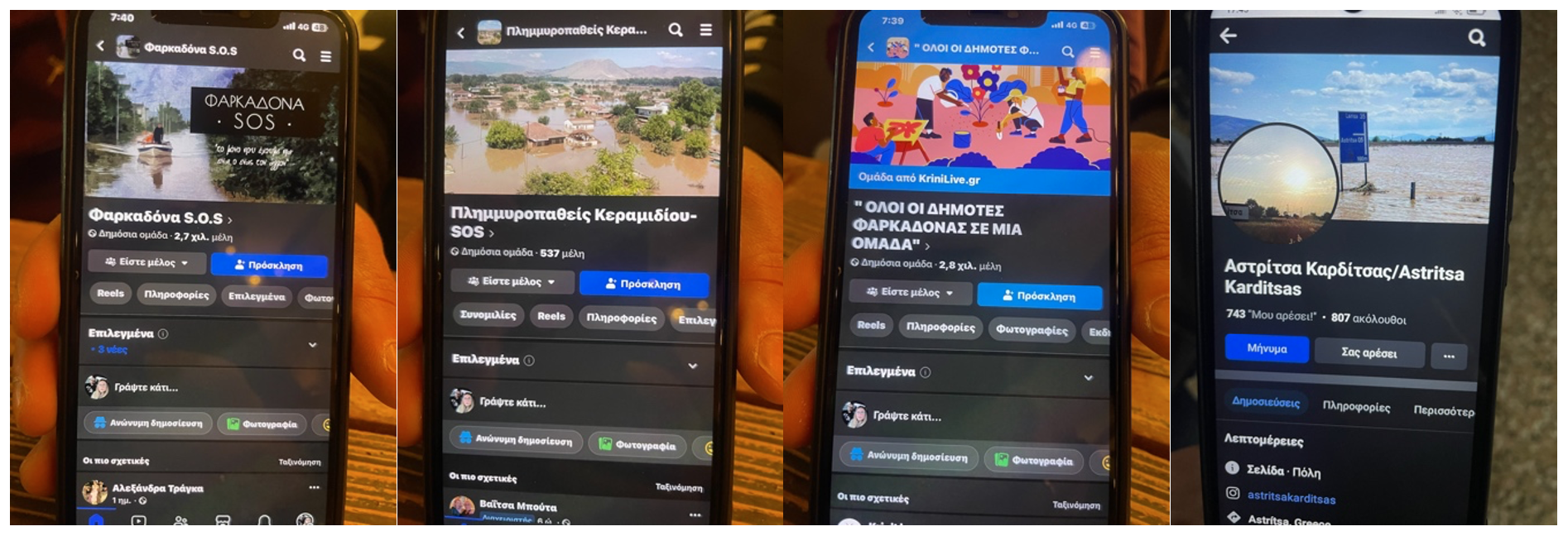

Parallel to solidarity efforts on the ground, digital platforms such as “Farkadona S.O.S,” “Flood victims of Keramidi – SOS,” “Astritsa Karditsas,” and the Viber group “Flood Victims’ Committee” play a crucial role in the ecology of communication. For digitally connected citizens, these spaces offer platforms for real-time information sharing, emergency alerts, and mobilisation of resources and volunteers. They complement the physical efforts of groups like the Collective Soup Kitchen by expanding the reach of communication, allowing for the rapid dissemination of information and the coordination of aid. While the Collective Soup Kitchen addresses immediate physical needs and fosters a sense of community through direct interaction, the digital groups ensure that the “managers of the villages” (this is how young and middle-aged individuals with smartphones in their villages self-declare themselves) have access to important information they can pass onto their fellow residents.

Gatekeepers and key nodes in the network: for most low-literate citizens, accessing social media groups/pages is either impossible (in absence of a smartphone) or very challenging (when lacking electricity). They often rely on intermediaries, such as family members or neighbours in the reception centre who serve as critical intermediaries, navigating the complex flow of information across diverse media landscapes. As an example, the “Flood Victims’ Committee”, a Viber group of 124 members was created by a 37-year-old woman, herself a displaced flood victim from Farkadona. Her initiative to establish a channel for disseminating crucial updates about compensations, medical aid, and food distribution highlights the proactive measures taken by a young and literate individual in the absence of formal information dissemination mechanisms. This effort specifically aims to bridge the information gap for those who, due to digital divides, find themselves excluded from traditional digital platforms.

In Koutsochero camp – previously used for refugees who were moved to other locations across Greece to host Storm Daniel’s flood victims – a 52-year-old hospital cleaner emerged as the sole conduit of information for 120 citizens of low socio-economic status who have sought refuge there since the end of September. Those residing in the camp, including ethnic minorities with origins in Albania and Ukraine, individuals of old age and/or with disabilities and mental health issues as well as individuals devoid of smartphones, constitute a segment of the population that is doubly marginalised: first by their socio-economic and health conditions, and second by their limited access to digital information channels.

The individuals assuming the role of gatekeepers or key nodes undertake a mission fraught with challenges, yet essential for the cohesion and resilience of their communities. Intermediaries become the linchpin in a chain of communication that seeks to ensure that critical support and information reaches excluded members of the community and no one is left behind in times of crisis. Their work becomes a critical bridge over the digital divide, ensuring that in the midst of turmoil, information – the currency of the modern age – remains accessible to all, thereby safeguarding the wellbeing and continuity of the community fabric.

Information Poverty and the failed promise of techno-solutionism

Information poverty is not merely the absence of technological tools but rather the inability to access, interpret, and utilise information critical for daily living and emergency situations. The disruption caused by Storm Daniel has further marginalised those already on the periphery of digital connectivity. These groups find themselves in a vicious cycle where their lack of access to digital platforms and devices impedes their ability to receive timely updates.

Contrary to Greece’s attempts to thrive in technological advancements, the plight of climate refugees in Thessaly highlights the complex challenges of digital inequalities in the wake of environmental disasters. Our findings call into question a techno-solutionist approach – according to which complex socio-political issues can be solved with technology – to addressing complex humanitarian crises (for example see a mobile-based application called ‘Disaster Alert for BD’ launched in Bangladesh in 2020 for effective disaster preparedness).

While digital platforms and technologies have the potential to facilitate communication, coordinate aid, and support self-organised action among affected populations, the reality on the ground in Thessaly (and regions with similar demographic characteristics across the world) reveals a different picture. The digital divide not only perpetuates existing vulnerabilities but also exacerbates the socio-economic disparities within crisis-affected systems. Particularly relevant in this context is Madianou’s critique of techno-colonialism which emphasises that albeit well-intentioned, technological approaches can often overlook the actual needs and capabilities of those in crisis.

As we reflect on the lessons learned from the aftermath of Storm Daniel, addressing such challenges requires a holistic approach that recognises the multifaceted nature of information poverty and its implications for community resilience and recovery. By implementing targeted strategies to enhance digital access, literacy, and inclusive communication, we can begin to bridge the digital divide. The path forward must involve an effort to ensure equitable access to digital technologies, enhance digital literacy, and foster a more inclusive digital environment. By doing so, we can move towards a more resilient and supportive framework for all those affected by climate-induced displacement, ensuring that the benefits of digital technology reach those who need them most.

This post represents the views of the authors and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.