Credit: D. Hoherd, CC BY-NC 2.0

Credit: D. Hoherd, CC BY-NC 2.0

Sonia Livingstone takes a closer look at the 2015 report by Childwise, a research agency that has been tracking UK children’s media use for almost twenty years. Sonia argues that the findings demand a steep learning curve from parents to keep up with the latest trends, but also challenges them to reach for their wallets. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Sonia Livingstone takes a closer look at the 2015 report by Childwise, a research agency that has been tracking UK children’s media use for almost twenty years. Sonia argues that the findings demand a steep learning curve from parents to keep up with the latest trends, but also challenges them to reach for their wallets. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

It will surprise no-one to learn how access to the internet has become part of children’s daily lives, yet scrutiny of the statistics can be revealing – providing evidence to underpin our hunches, and highlighting some key points to consider.

The market research agency Childwise has been tracking UK children’s media uses since 1997 – the very beginning of the internet for most of us. I remember interviewing a 6 year-old girl in 1997 who asked, in a puzzled voice, “is the internet something you plug into the back of your TV?” (In that project, too, the exciting new device was the CD-ROM!)

In a decade and a half, our homes have been transformed – and I say ‘our’ because while the internet began life as an elite resource for the privileged few, it is now in the homes of nearly all 7-16 year olds in the UK.

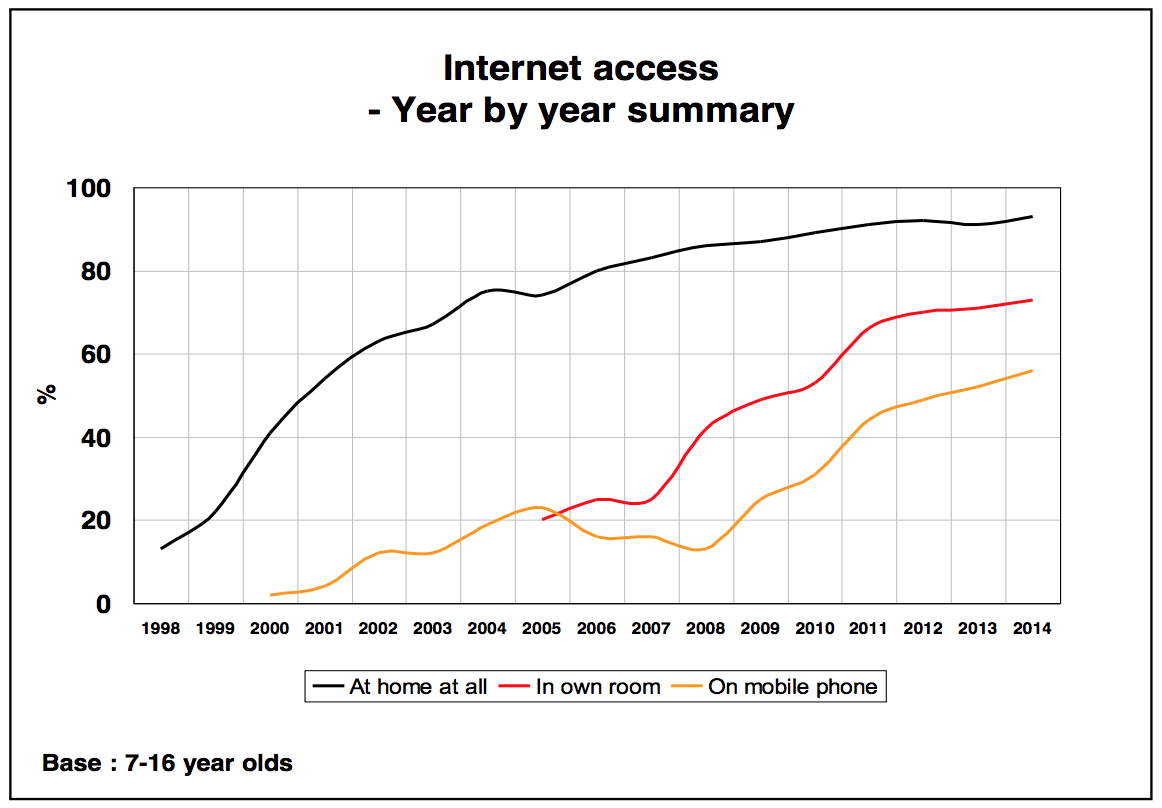

The personalisation of online experiences within the home – being no longer accessed via a desk top computer in the living room where parents can supervise – represents an even more recent and rapid transformation. As the graph shows, now children have internet access in their own room and, yet more recently, on their mobile phone. This has consequences for:

- How children feel about the internet – it’s theirs and it’s private;

- How parents can manage their children’s internet use – it’s hard to supervise and it’s hard to share;

- The degree to which parents worry about their roles when it comes to technology – no wonder that we have seen a growth in technological resources for monitoring and filtering children’s internet use, no matter that some worry that this means an ‘outsourcing’ of parenting tasks to digital services.

Is the internet really equalising? Yes and no. The overall picture is of most people gaining internet access. But when new devices enter the home, their relatively high cost mean it is generally more available to wealthier families and, within the family, more to older children and boys.

- Thus in 2000, 19% of boys and 22% of 11-16 year olds had their own computer compared with 15% of girls and 13% of 5-10 year olds. By 2014, the gender difference had more or less disappeared (though the age difference remains).

- Ofcom’s data add a little information about socio-economic status by revealing no differences for possession of a games console (around 4 in 5 of all homes with children aged 5-15) but a considerable difference for PC/laptop based PC access (98% of AB homes compared with 74% of DE homes) and for tablet computers (87% of AB homes compared with 55% of DE homes).

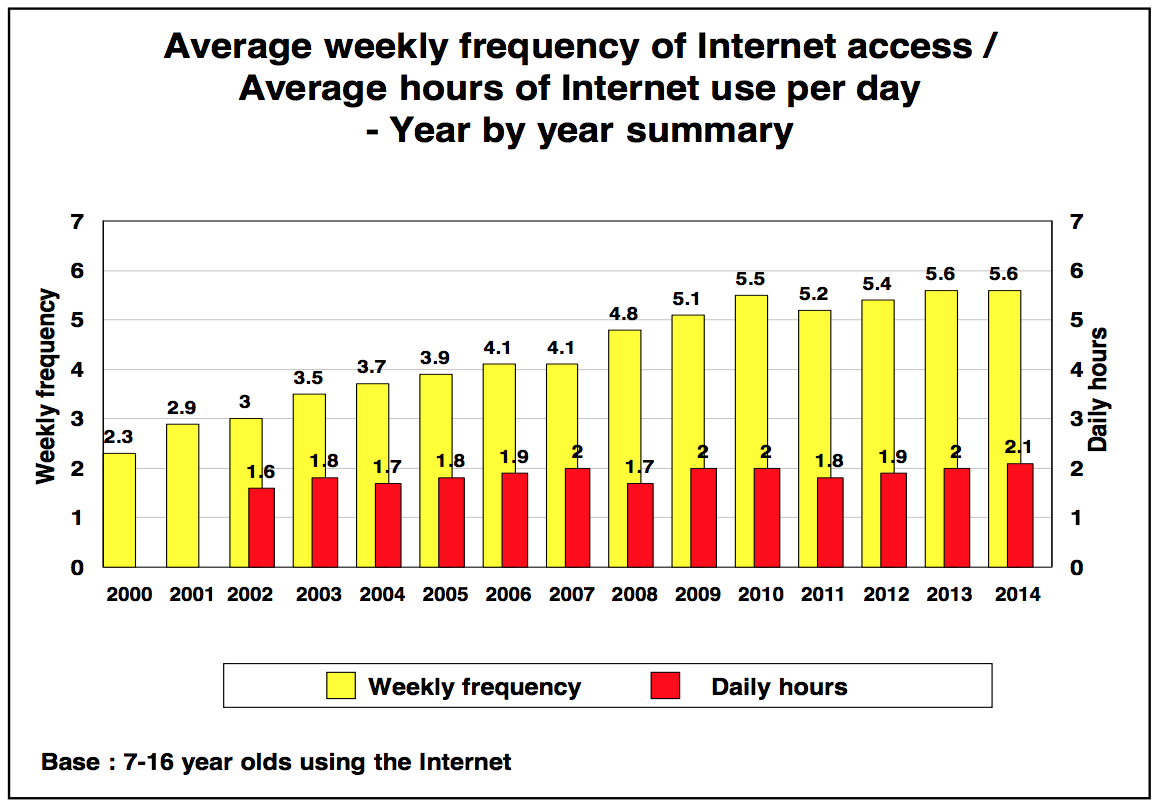

Does this mean children are constantly connected? The graph below suggests a steady increase in frequency over the years (most people are now online almost every day), but not such a great increase in time spent. Children’s disposable time is, of course, constrained by time spent at school, time on other media and, despite parental fears to the contrary, homework and sleep. Parents wishing to implement a rule might take heart here – if they chose to limit their children’s online access to two hours per day, they could point to this as perfectly ‘average’ rather than outrageously low!

And what are they doing online? Here we see where some of the pressures on parents arise, for keeping up with fast changing trends is definitely a challenge. In the Childwise data, we see:

- Minecraft’s popularity doubling from 17% of 5-16 year olds in 2012 to 38% in 2014;

- Moshi Monster’s popularity halving over the same period (from 26% to 15%);

- Instagram tripled its users from 13% in 2012 to 38% in 2014 (while Facebook is holding steady at just under half of 5-16 year olds);

For parents, this demands not only a steep learning curve but also a never-ending effort to keep abreast of the latest trend, if they wish to guide, protect or share in their children’s online lives.

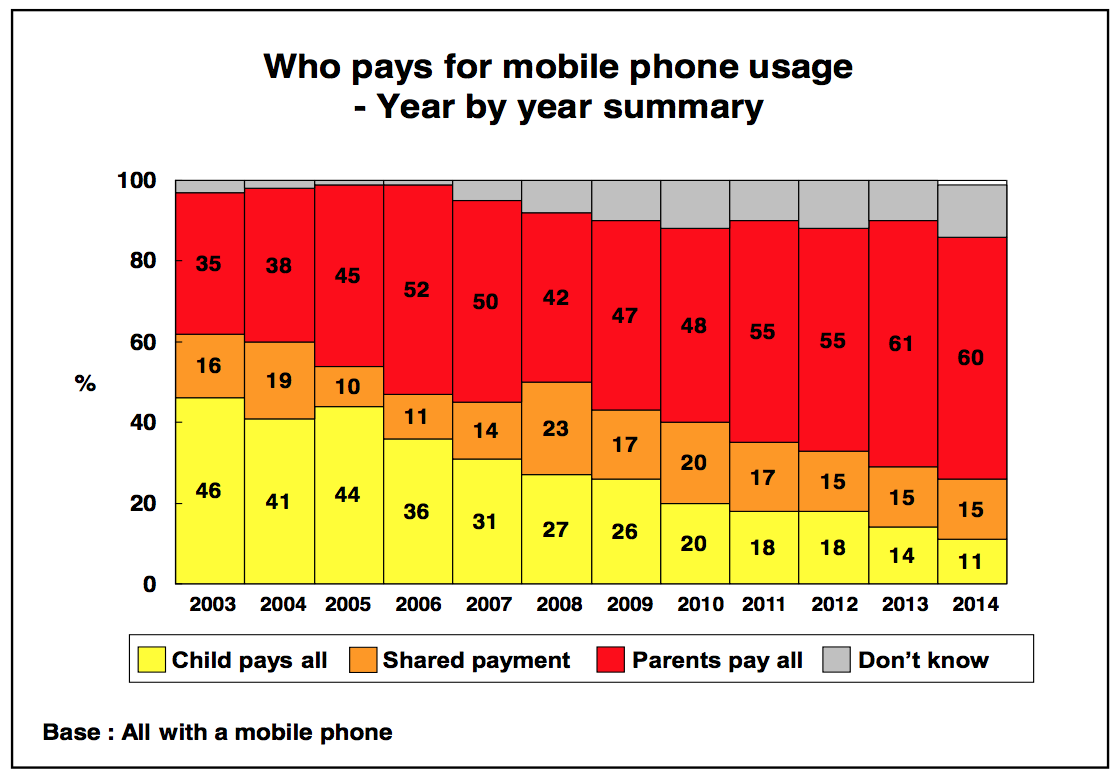

Ironically, the cost of this personalised access has shifted over the same period from a cost to be borne by children to one shouldered by parents! In our research interviews, some parents say that at least this gives them some power in negotiating use of digital devices with their children. But others see it as a symptom of the consumer society – children want to communicate freely and privately with friends and the wider world, but they are not learning that responsibilities go with such privileges.

So it indeed seems that children’s internet use at home is increasingly personalised, mobile and equalising – while parents pick up the cost. In our research, we are exploring the degree to which parents themselves are creating this present – and future – for their children. Yet we are also struck by the degree to which parents feel swamped by digital technologies. Not only do they often feel unable to control the deluge of devices entering the home but, interestingly, the consequences of this more personalised and privatised experience within the family seems to crystalize their wider anxieties about bringing up children today.

NOTES

Methodology: over time, Childwise has expanded its age range from 7-16 to 5-16 years old and its sample size from 800 to 1000 schools. They now conduct online surveys with children via an established panel of 1000 schools across the UK. Since their reports are produced for industry and so are rather expensive, I’m glad to be able to have permission to report some findings here.