Sonia Livingstone explores how school and learning, home and family, and peer groups impact and shape children’s use of digital media. Sonia, together with Julian Sefton-Green, followed a class of London teenagers for a year to find out more about how they are, or in some cases are not, connecting online. The book about this research project¹, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, just came out. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. [Header image credit: F. Osorio, CC BY 2.0]

Sonia Livingstone explores how school and learning, home and family, and peer groups impact and shape children’s use of digital media. Sonia, together with Julian Sefton-Green, followed a class of London teenagers for a year to find out more about how they are, or in some cases are not, connecting online. The book about this research project¹, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, just came out. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. [Header image credit: F. Osorio, CC BY 2.0]

School

How can researchers study children’s digital and social lives? Our study of The class began at school, an institution that plays a defining role in young people’s lives. We soon realised that how they made sense of their classroom experiences and school life was largely unaffected by the fierce discursive struggle going on above their heads among governments, pedagogues, technologists and pundits seeking to redefine the purposes and practices of education in the digital, networked age. But school had nonetheless been reshaped by these struggles in ways that mattered for the students, making their school experience in some ways continuous with that of their parents, but in other ways very different.

Home and family

Home and family occupies another important part of the picture, and here, too, there are lively public debates about transformations in childhood. These were evident in the teachers’ speculations about students’ home lives, since they rarely gained the direct insight into the home that we were able to. Debates about childhood and family life were also visible in the parents’ anxieties (more so than in their children’s accounts), often surfacing in their fraught reflections on managing the influx of digital devices into the home.

Peer group influence

For young people, the peer group is the third and most crucial element. This was the hardest for us to observe directly, yet the young people were keen to tell us about it when we got to know them. We wanted to understand the range of their relationships, from personal friendships through to the largely civil relations of the class. We talked to them about their wide and diverse digital social networks and, for many in the class, their family connections with their country of origin as well as within various diaspora.

Community, culture and society

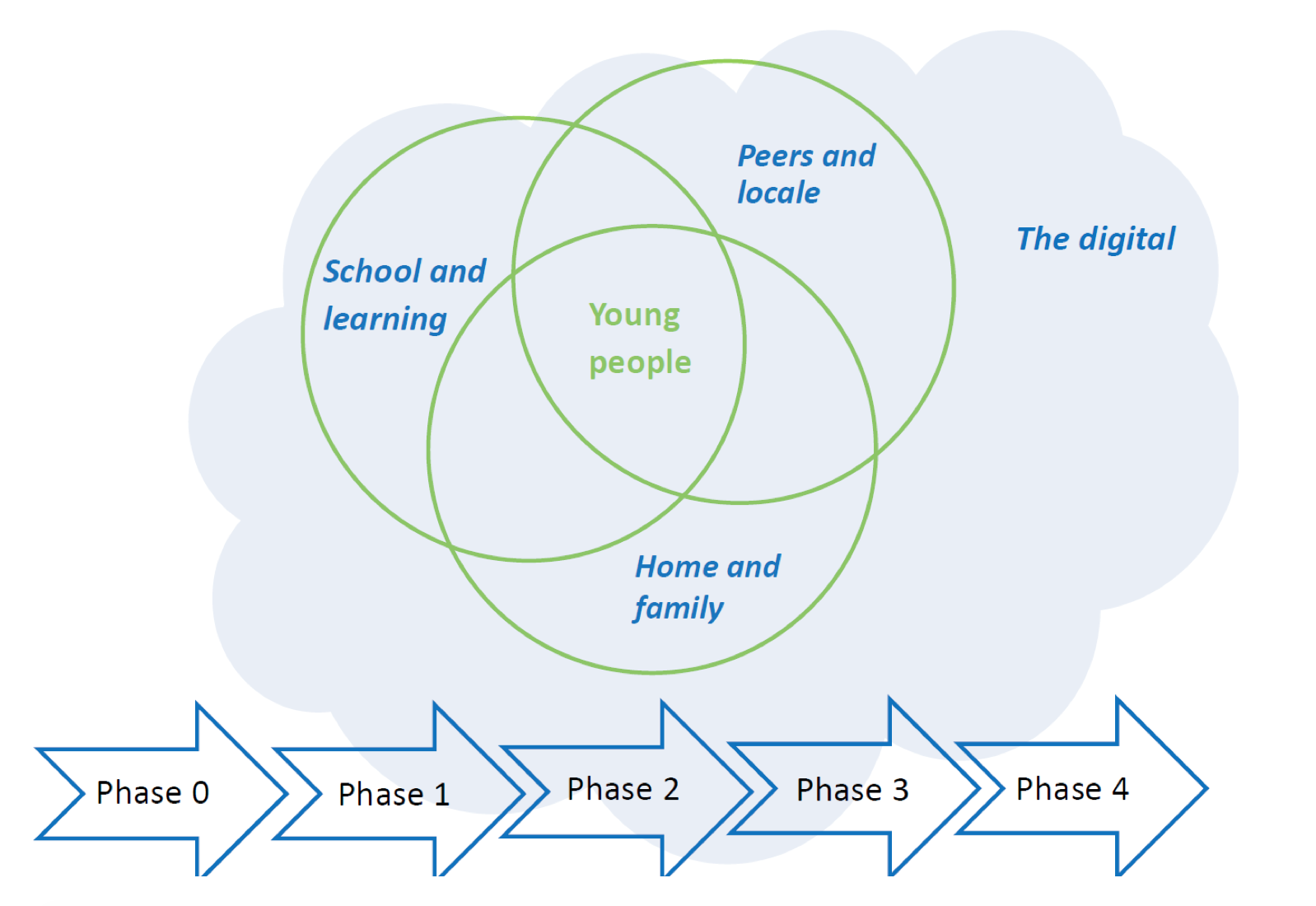

Each of these spheres – or increasingly, networks – of school, home and peer groups is now substantially mediated by mobile and online technologies, yet as we found, the forms taken by these mediating processes were sometimes surprising, working both to connect and to disconnect in complex ways.

Around these three intersecting spheres we can draw the wider circle of community and culture, shaped by urban, regional and ethnic influences and cross-cut by social class. Beyond this is the wider society, a world that the young people know partly through the news, film, television and social media, and partly through living cheek-by-jowl with others from all walks of life. To grasp as much of this as we could, we observed the students’ social interactions during and around lessons, visited their homes and families, joined in some out-of-school activities, and peeked into their digital worlds.

Linking the three domains

We envisaged the young people’s lives in terms of a Venn diagram, with three more-or-less interconnected circles representing school, home and peers. We prioritised the links and contrasts among the different social worlds that this group of young people inhabited and yet shared with each other. How was home talked about at school, for instance, or school at home?

We then mapped these three domains onto the three terms of the school year, resulting in a multi-sited, sequential research design. We began in the classroom, then visited the students at home, and then explored their connections with friends and peers, extended family or other activities in a range of places, both online and offline. Finally, we revisited the class – either at home or at school – at the start of the following school year, inviting them to look back on the year we had spent with them, to tell their story of ‘Year 9’.

The findings

While our first impressions set up a host of possibilities to be explored as the research progressed, we grounded our analysis in the detailed descriptions of the texture of the experiences, and the various economic, social and cultural resources that the class could draw on – the houses they lived in, the bedrooms they had to themselves or had to share, or the kinds of technology bought for them by their parents. We also listened to the many expectations, hopes and anxieties that intertwined and held them and those around them, shaping their trajectories. This posed us with some tricky questions of research ethics in the digital age.

We sought to recognise young people’s agency and voice, although the strong influences and constraints they faced demanded that we also attended to the views of their parents and teachers as well as of wider society, not least because these also found their expression in what the young people said to us. We began to think more of education and family as the two dominant institutions within and sometimes against which young people negotiated their present and future possibilities. Within this, friendships – pursued online and face-to-face, including in the in-between places in and around their home and locale – allowed for exploration and enjoyment of alternative modes of connection and disconnection.

NOTES

¹ The class: Living and learning in the digital age, published in May 2016, is based on a research project funded as part of the Connected Learning Research Network by the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media Learning initiative.