Most children love YouTube, but what do they love about it? Sonia Livingstone unpacks the individual stories behind the shared fascination. Together with Julian Sefton-Green, she followed a class of London teenagers for a year to find out more about how they are, or in some cases are not, connecting online. The book about this research project¹, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, just came out. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. Lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project, she was recently asked to give a keynote lecture to the YouTube Conference 2016, and so wrote this post to capture some key points. [Header image credit: L. Hidalgo, CC BY 2.0]

Most children love YouTube, but what do they love about it? Sonia Livingstone unpacks the individual stories behind the shared fascination. Together with Julian Sefton-Green, she followed a class of London teenagers for a year to find out more about how they are, or in some cases are not, connecting online. The book about this research project¹, The Class: living and learning in the digital age, just came out. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. Lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project, she was recently asked to give a keynote lecture to the YouTube Conference 2016, and so wrote this post to capture some key points. [Header image credit: L. Hidalgo, CC BY 2.0]

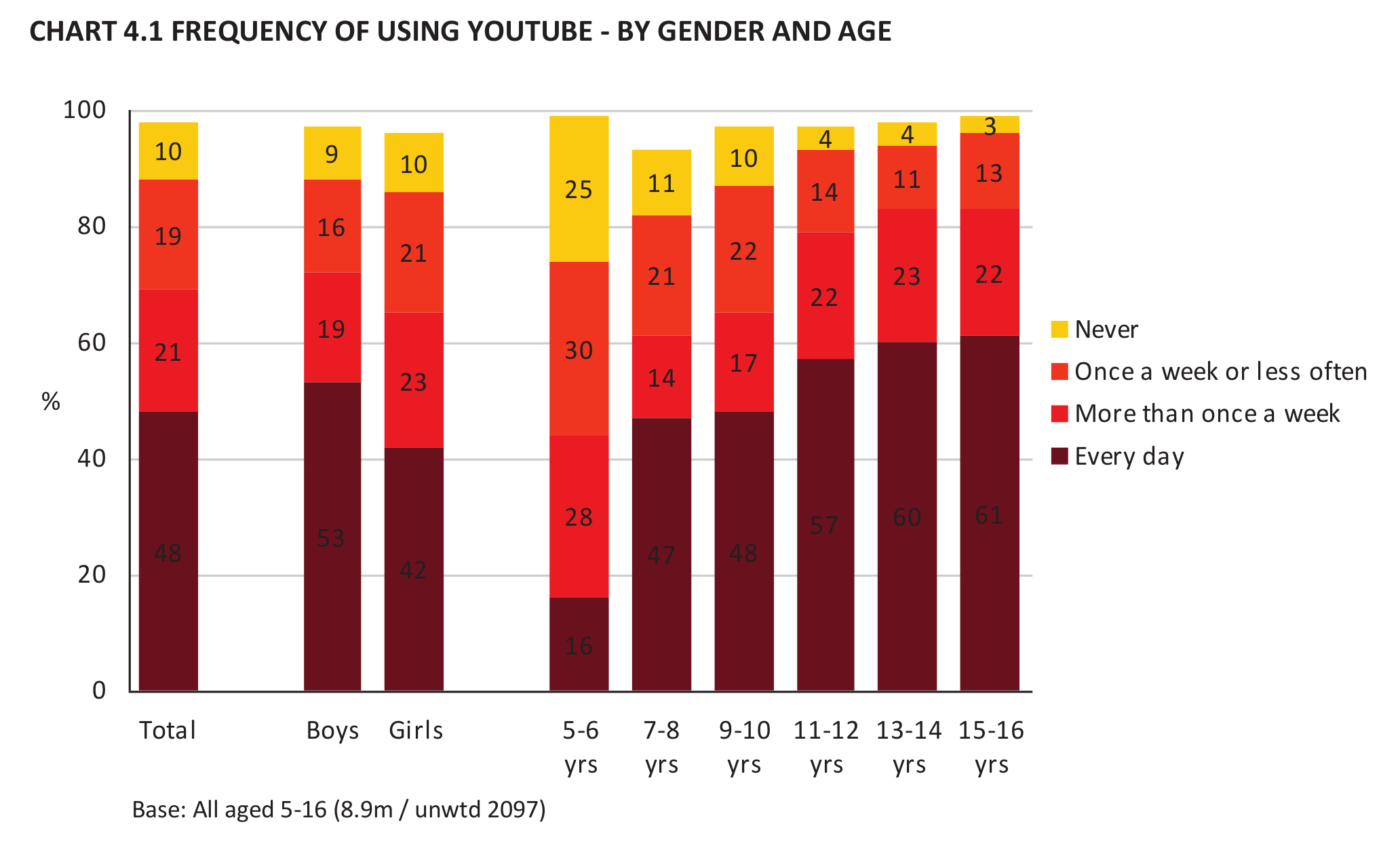

The statistics show that most children love YouTube – as is obvious from the chart below. But such charts seem to homogenise children’s experiences, whereas my ethnographic research with just 28 fairly ordinary 13-14 year olds in The Class revealed 28 different stories about YouTube.

Imagine, then, such diversity scaled up to the vast number of YouTube “users” to realise that “use” is a far-from-straightforward activity. Rather, using YouTube brings together complexities of meanings, practices, texts and contexts. This matters, because it’s so easy to make sweeping generalisations about children’s digital experiences, opening the door to hasty dismissals (they’re wasting their time) or, occasionally, celebration (they’re all digital creatives).

As ever, the evidence shows life is more complex, and more interesting. For after a year or more spent with the class in school, home, with their friends and online, we gained a more nuanced understanding of how and why they love YouTube than one could get from their parents and teachers who, as they told us, simply thought the kids were wasting their time watching silly videos about people falling off walls and cute kittens.

Even when they did just watch what Yusuf called “funny stuff”, there were some deeper reasons. Yusuf, for instance, had parents who held out high expectations for his educational achievement, though there was little money at home. In addition to attending school, followed on several days a week by Koran school attendance, his father had set himself up as his ‘head teacher’ at home, with expensively purchased educational resources and star charts on the wall at home to track his progress. No wonder chilling out with YouTube provided a welcome respite.

Adriana, by contrast, enjoyed her status as the popular if naughty girl in the heart of the class, but knew it was all about to come to an end. As the daughter of a professional middle-class family, it would soon be time to knuckle down and study. So when she told us she loves YouTube for its make-up tutorials, she was surely celebrating her last moment of irresponsible girlishness.

Joel was a sadder case. In an unusually forthcoming interview for this shy and seemingly unhappy boy on the edge of the social scene, he talked with enthusiasm about using YouTube tutorials combined with music-making software and mixing decks to record his own music on the computer. And yet the interview unravelled when I pushed a little further – for such activities were not practically possible at home (or indeed in the rather standardised music technology lessons I witnessed at school). Rather, his account was aspirational; these are things he has heard about and hopes to follow up in the future.

Gideon was something of a paradox. At school, and online, he stood right at the centre of the social network – the boy who cracked jokes, played football and computer games with the boys, had twice as many friends on Facebook as anyone else. Yet at home, when we got to know him better, he was quieter, revealing some past difficulties requiring ‘anger management’ classes and, now, a quiet reliance on the succour of his immediate family. Interestingly, his use of YouTube was fairly edgy – ‘America’s hardest prisons’, ‘Angry Scottish guy kicks and snatches’, ‘Jamaican gangs.’ Perhaps he was working through some residual anger? Or perhaps he was gathering the material to impress his classmates the next day to maintain his edgy reputation?

Alice didn’t really bother with YouTube much – she watched it a bit but, on getting to know her better, it would be wrong to characterise her as passive or disengaged. For Alice turned out to be incredibly active in her local community – with babysitting, Girl Guides, community events – and she also did singing, trampolining, netball and ice-skating out of school, and arts and crafts, DIY and photography at home. Is it really necessary, one wonders, that a 13-year old girl also gets creative in uploading stuff to YouTube for society to celebrate her achievements?

In fact, just six teens in the class had uploaded anything, roughly fitting in with the research which shows, over and again, that while many engage with interactive content online, only a minority even of the ‘digital native’ generation makes and uploads their own content. And among those that do, real questions arise as to how these interest-driven activities can be supported and sustained. Abby and Salma, for instance, spent a happy day setting up a YouTube channel and posting 8-10 episodes of ‘the Abby and Salma show’ before retreating in mortification when their history teacher got wind of their efforts and showed everyone.

Megan had a period of making videos and uploading them to YouTube too, describing herself as “obsessed” with searching YouTube, going to meet-ups and so forth. But for her, too, this had become embarrassing, and she turned her attention to a private exploration of identity in Tumblr, as we describe in chapter 4 of our book.

Nick was more persistent, having paired up with a friend with editing skills: Nick would make videos of his Xbox game play and, once edited by his friend, uploaded them to YouTube to create the tutorials enjoyed by others. It’s interesting to speculate why Nick took this step but Adam – who regarded himself as the best player in the class – did not. For Adam, using YouTube to watch the walk-throughs of tricky moments in the game seemed enough; then he could return to the game itself, his real passion.

Last, Giselle, perhaps the most creative girl in the class, had created her own YouTube channel for stop-frame animation – like Nick, Abby and Salma, made with a friend as a collaborative duo – which exhibited some skill and gained several hundred views before she, too, gave it up. However, as a later interview discovered, Giselle is pursuing an artistic career, significantly helped by her artistic parents, so perhaps all this is grist to the mill, even though her current passion is paint.

In sum, our time spent with a class of 13-14 year olds in a cosmopolitan suburban secondary school uncovered very diverse reasons for engaging with YouTube, resulting in a diversity of uses of which I could only illustrate a few here. This diversity depends on home resources – financial, parental, cultural – and on each young person’s particular bent and interests. On the one hand, several of these stories invite the question: with more support, could the kids have taken their creative first steps much further, gaining vital skills for the digital age? On the other hand, their stories invite the observation that, given everything else that’s going on in their lives, engaging with YouTube may not be their top priority.

NOTES

¹ The class: Living and learning in the digital age, published in May 2016, is based on a research project funded as part of the Connected Learning Research Network by the MacArthur Foundation’s Digital Media Learning initiative.