Vikki Katz shares key insights into how lower-income families in the U.S. with children in school are meaningfully connected to the internet. She argues that this is especially important to ensuring equal access to learning opportunities. Vikki is an Associate Professor at Rutgers University’s School of Communication and Information, and Senior Research Scientist at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. She is also principal investigator in the Digital Equity and Opportunity for All project, which seeks to understand how lower-income families respond to initiatives, and how they make decisions about integrating technology into their family routines and learning activities. [Header image credit: D. Goehring, CC BY 2.0]

Vikki Katz shares key insights into how lower-income families in the U.S. with children in school are meaningfully connected to the internet. She argues that this is especially important to ensuring equal access to learning opportunities. Vikki is an Associate Professor at Rutgers University’s School of Communication and Information, and Senior Research Scientist at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. She is also principal investigator in the Digital Equity and Opportunity for All project, which seeks to understand how lower-income families respond to initiatives, and how they make decisions about integrating technology into their family routines and learning activities. [Header image credit: D. Goehring, CC BY 2.0]

Digital inequality (constrained access to the internet and digital devices) is disproportionately experienced by children and families who experience other, more entrenched forms of social inequality. Given how many opportunities are now online, this has prompted national efforts to increase broadband connectivity in under-served U.S. public schools, and (to a more limited extent) to make affordable options available for low-income families to connect at home.

In this blog post I discuss some key findings from a report I co-authored with Victoria Rideout, based on a representative telephone survey of 1,200 U.S. parents with elementary and middle school-aged children living below the median household income for their demographic (>$65,000 a year). The survey is unusual for two key reasons. First, we only surveyed lower-income parents, so we didn’t treat family income merely as a demographic variable. Second, our survey questions were informed by interviews previously conducted with 170 low-income parents and their school-age children about these issues, in three U.S. states.

Here are three of our most important findings.

Finding #1: Most lower-income families have an internet connection, but many are ‘under-connected’ in some way

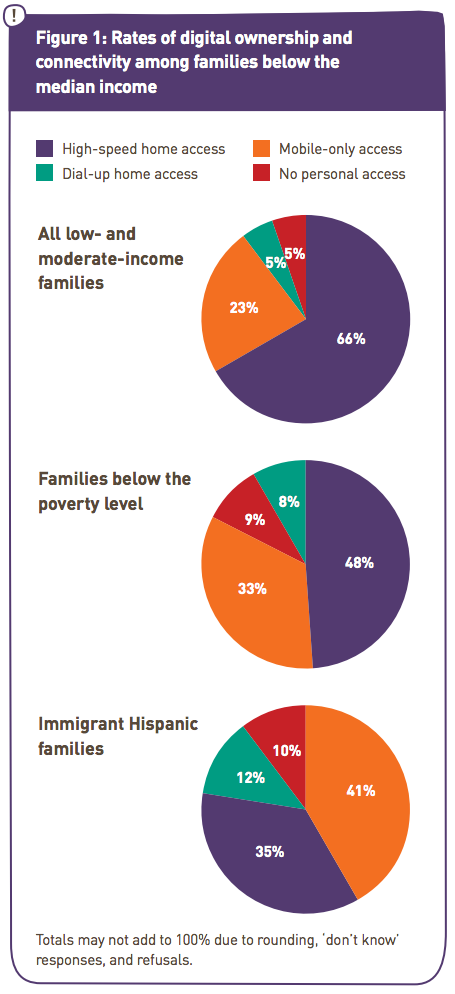

Almost all of the surveyed families have some kind of internet access (94%), whether via a computer at home or a mobile device with a data plan. Even among families living below the U.S. government’s federal poverty threshold, 91% report being online.

Almost all of the surveyed families have some kind of internet access (94%), whether via a computer at home or a mobile device with a data plan. Even among families living below the U.S. government’s federal poverty threshold, 91% report being online.

Many families are less connected than they would like to be, and many report disruptions to their online experiences:

- Among parents with home internet access through a desktop or laptop computer, 52% say their internet is too slow, 26% say too many people share the computer for them to have enough time on it, and 20% say their internet has been cut off in the last year due to non-payment.

- About one-quarter (23%) have mobile-only internet access through a smartphone or tablet. Of these, 29% have hit their plan’s data limits in the past year, 24% have had their phone service cut off in the last year due to non-payment, and 21% say that too many people share the device to have the time on it that they need.

This shows that it’s no longer enough for researchers or policy-makers to ask whether or not families have internet access – the quality and consistency of that connection is also very important.

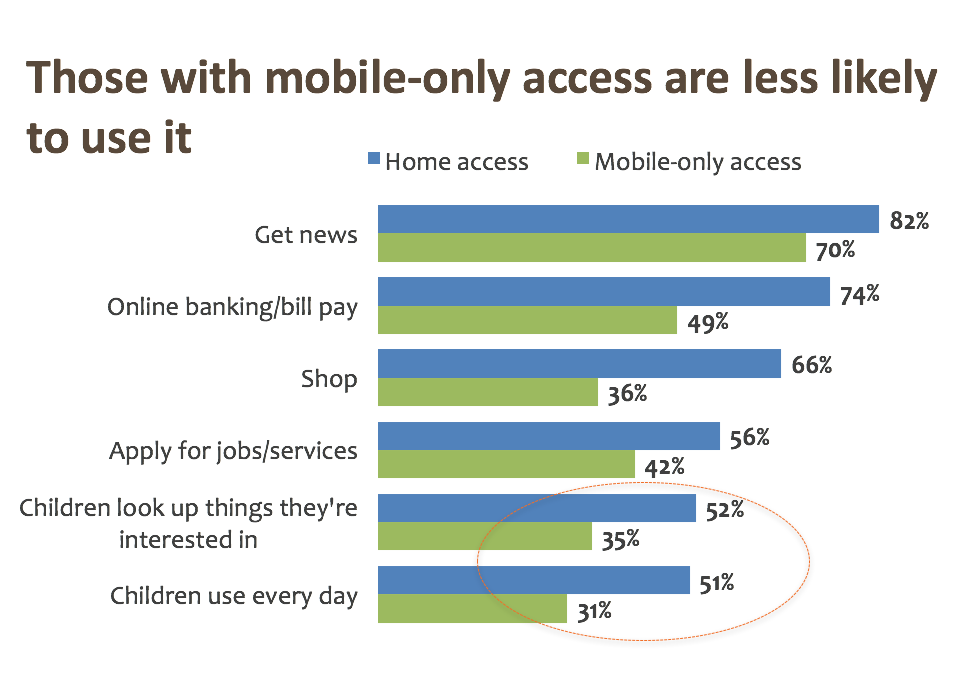

Finding #2: Mobile-only access is not the same as home access Mobile devices are not the solution to digital inequality. While mobile-only access is definitely better than no access, more complex tasks (e.g., researching and writing a homework assignment or completing a job application) are both challenging and frustrating on a mobile device. Families that only have access via a smartphone or tablet use the internet less frequently, and for a narrower set of activities, than families who have a laptop or desktop at home:

Mobile devices are not the solution to digital inequality. While mobile-only access is definitely better than no access, more complex tasks (e.g., researching and writing a homework assignment or completing a job application) are both challenging and frustrating on a mobile device. Families that only have access via a smartphone or tablet use the internet less frequently, and for a narrower set of activities, than families who have a laptop or desktop at home:

- Mobile-only parents are less likely to shop online (36% vs 66% with home access), use online banking or bill paying (49% vs 74%), apply for jobs or services online (42% vs 56%), or follow local news online (70% vs 82%).

- The same is true for children in mobile-only families – they are less likely to use the internet daily (31% vs 51% with home access), or to look up information online about things they are interested in (35% vs 52%).

These differences are particularly worrying, because frequent access is positively associated with building digital skills. And engaging in ‘interest-driven learning’, when children’s own interests and curiosities drive their learning activities (as opposed to being guided by parents or teachers), helps develop their love of learning. That children with mobile-only access are so much less likely to have daily access or explore their interests online – even in comparison to other children growing up in the lower economic half of U.S. families – is cause for real concern.

Finding #3: While many families are under-connected, parents and children are making the most of the connectivity they have

Most parents and children regularly help each other learn with, and through, technology:

Most parents and children regularly help each other learn with, and through, technology:

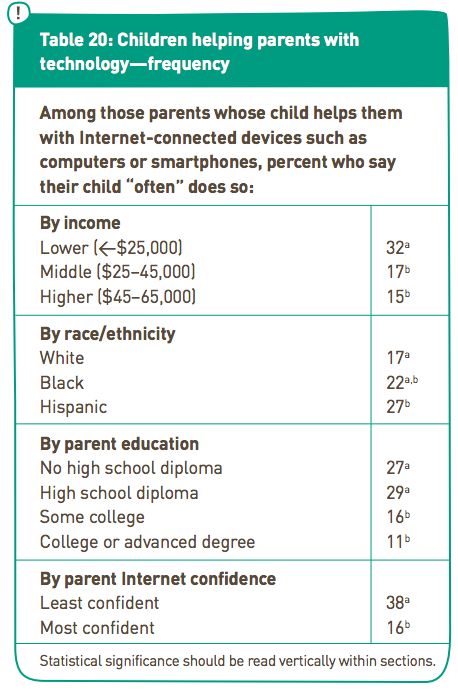

- In families where the parent and child both use the internet, 77% of parents have helped their children use technology, and 53% say their children have helped them do the same. These proportions vary significantly by race/ethnicity and parents’ dominant language and education level.

- Siblings are also important learning partners. Among families with more than one 6- to 13-year-old and a computer in the home, 81% of siblings help each other learn about computers or mobile devices either ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’.

These findings highlight the considerable assets lower-income families already have when it comes to engaging technology for learning. Local organisations can support and expand these family learning practices by providing opportunities for parents and children to further develop their skills or seek assistance with problems they encounter using technology. Efforts to achieve digital equity can, and should, treat families as motivated partners, because they’re already working to address digital challenges themselves.