Julian Sefton-Green explores what play is and what play is not, and whether it truly is ‘the work of the child’. Julian is an independent scholar working in education and the cultural and creative industries. He is currently leading the project Preparing for Creative Labour and is a principal research fellow at the Department of Media & Communication, LSE, a research associate at the University of Oslo and visiting professor at The Playful Learning Centre, University of Helsinki. [Header image credit: M.-Wiman-CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0]

Julian Sefton-Green explores what play is and what play is not, and whether it truly is ‘the work of the child’. Julian is an independent scholar working in education and the cultural and creative industries. He is currently leading the project Preparing for Creative Labour and is a principal research fellow at the Department of Media & Communication, LSE, a research associate at the University of Oslo and visiting professor at The Playful Learning Centre, University of Helsinki. [Header image credit: M.-Wiman-CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0]

Scandinavian countries have a deserved reputation for promoting the value of ‘play’ in education. In this context, however, play is neither frivolous nor something necessarily children are allowed to do by themselves, but frequently highly structured, offered as part of preschool and early years education.

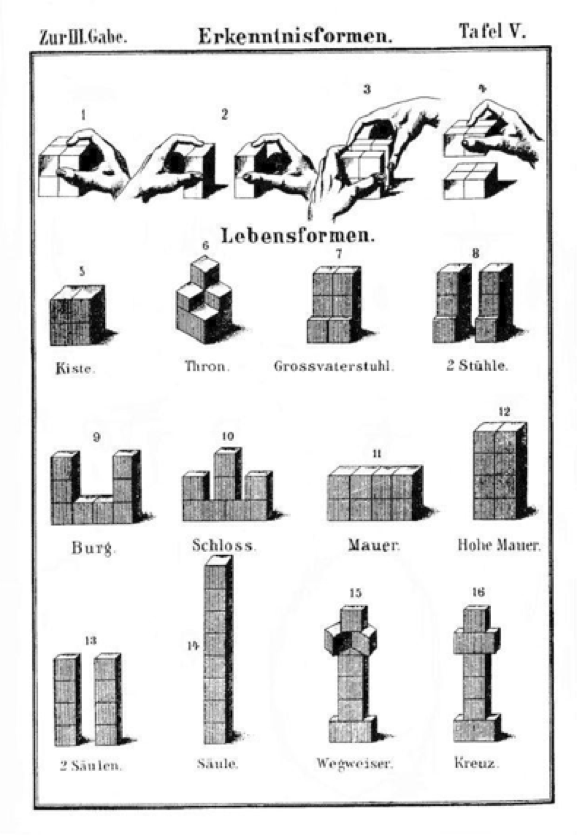

In recent years we have seen the growth of ‘edutainment’ and ‘gamification’, both of which show a blurring between the worlds of leisure, education and work. And within the private, commercially driven world of software (including games), there has been intense interest in developing learning-driven activities and curriculum, sometimes from the historical tradition going back two centuries, to the educational ‘toys’ developed by Froebel, and sometimes finding ways of using new digital media to create games, puzzles, learning environments and challenges as new ways of teaching and learning.

In recent years we have seen the growth of ‘edutainment’ and ‘gamification’, both of which show a blurring between the worlds of leisure, education and work. And within the private, commercially driven world of software (including games), there has been intense interest in developing learning-driven activities and curriculum, sometimes from the historical tradition going back two centuries, to the educational ‘toys’ developed by Froebel, and sometimes finding ways of using new digital media to create games, puzzles, learning environments and challenges as new ways of teaching and learning.

The debate about play

In turn, this changing focus on play from something that people thought was natural, and to an extent defined by how they grow up, has made it seem like a new responsibility for parents, leading them to question how they should encourage their children to play, and what the right kind of play is. And most importantly for the debates here, to consider in what ways digital play is good or bad….

This kind of anxiety should really make us think about what play is in the first place, and in what ways we can make learning playful. The University of Helsinki set up the Playful Learning Center, both to develop a research agenda within this new ecology, and to act as a ‘living lab’ to develop products and ideas, all of which should contribute to a vision of what playful learning is. It has recently published a manifesto to encourage debate about what we value in play, and what its place should be in education.

Play means many things

Although a seemingly common and incontrovertible term, ‘play’ itself has meant a variety of things in the past, and is continuing to take on new definitions now. One of the most comprehensive studies of play, entitled The ambiguity of play by Brian Sutton-Smith, draws attention to the fact that although we all think we know what play is, in fact we use the term to cover a multitude of activities. In this landmark study, Sutton-Smith describes different theories of play as different kinds of rhetoric, because he argues that it is impossible to state with any certainty what play is, only what different theorists have claimed it could be.

Because play is such a nebulous and unclear concept, different theories, explanations or definitions only really make sense in the context of broader value systems and underlying ideological values, so Sutton-Smith identifies seven rhetorics of play: as progress, as fate, as power, as identity, as the imaginary, of the self, and finally, as frivolous.

Playfulness

Academics, however, are keen to make the point that whatever definition of play they espouse, playfulness (or, as used adjectivally in the key phrase ‘playful learning’) is where aspects of play are transferred across into other domains.

Miguel Sicart states that playfulness is more of an attitude or a modality, where we can take ‘the attitude of play without the activity … [it] is a way of engaging with particular contexts and objects that is similar to play but respects the purposes and goals of that object or context.’

The binaries of play

As a number of commentators have noted over the years, play is often defined in terms of what it is not. So, play is not work; play is not serious; play is not imposed; play has no extrinsic validation; play has no external purpose; play is not a good use of time; and, of course, if it is play, can it also be learning? This doesn’t always mean that the inverse of these values is always true: play is natural (but can be learned and even taught); play is spontaneous (but can be stimulated under certain conditions); play has its own intrinsic rewards (but people play to win); play is fun (but note the prevalent use of the term ‘serious games’, or what Seymour Papert has called ‘hard fun’).

Playing with these binaries and exploring the tensions (and continuities) between them has often proved a productive way to define and promulgate the values of play. Thus, Maria Montessori’s famous dictum that ‘play is the work of the child’ resonates because of the historical distinction between the domains of children and adults, and the increasing importance of leisure activities in the industrialised and urbanised workforces of the 20th century.

Play and learning

So what happens to this fluidity of interpretation when playfulness is yoked together with learning? After all, it is much more difficult to imagine or conceptualise a state of not learning or even unlearning in the same way that we can imagine alternative valorisations of play and playfulness.

Indeed, by joining together playfulness and learning, one key challenge must be whether the possible range of meanings that exist within both terms when considered distinctly are immediately constrained when joined together. In other words, how much of what play is not is still plausible in terms of an attitude or a modality, in the formulation of playful learning?