The forthcoming General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force next month, and proposes that companies should gain parental consent before processing the personal data of children under a certain age. But what do parents think that age should be? In this blogpost, LSE’s Sonia Livingstone and Kjartan Ólafsson of the University of Akureyri present findings from a new UK survey of parents with children who are aged 0-17 years old. [Header image credit: Photo by Jacob Ufkes on Unsplash.com]

The forthcoming General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force next month, and proposes that companies should gain parental consent before processing the personal data of children under a certain age. But what do parents think that age should be? In this blogpost, LSE’s Sonia Livingstone and Kjartan Ólafsson of the University of Akureyri present findings from a new UK survey of parents with children who are aged 0-17 years old. [Header image credit: Photo by Jacob Ufkes on Unsplash.com]

In all the recent discussion over social media data exploitation, licit or illicit, with or without consent, urging people to lock down privacy settings or even delete their profiles, the ‘user’ is constantly assumed to be an adult – responsible for their decisions about when to allow information society services to monetise their personal data. But who is looking out for children and their data privacy?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), coming into force on 25th May 2018, proposes that for children under a certain age, companies should gain parental consent before processing their personal data.

But what is under-age? The GDPR proposed 16 as the age of consent, albeit for largely unexplained reasons. It then allowed member states to reduce the age to 13, and the UK’s Data Protection Bill has proposed just that, resulting in a lower age of consent than in some European countries, but leaving unresolved the challenges of implementation.

In all this, it seems no-one has consulted parents. US research with parents suggests 13 is too young and, as Facebook reported, 77% of parents say they should be the ones to decide. So for the first time in the UK, the Parenting for a Digital Future project surveyed a nationally representative sample of 2032 parents of 0-17 year olds in November 2017.

As we show, overall parents think 13 is about right, but parents of teens – to whom this decision actually matters in practice – think 13 is too young.

The older their child, the longer parents want oversight of their internet use

Our survey asked parents:

“At what age do you think your child will be or was old enough to make their own decisions about the websites or apps they use?

We’ll call this the “age of independence”, as we asked parents to assess their child’s maturity rather than the legal question of consent.

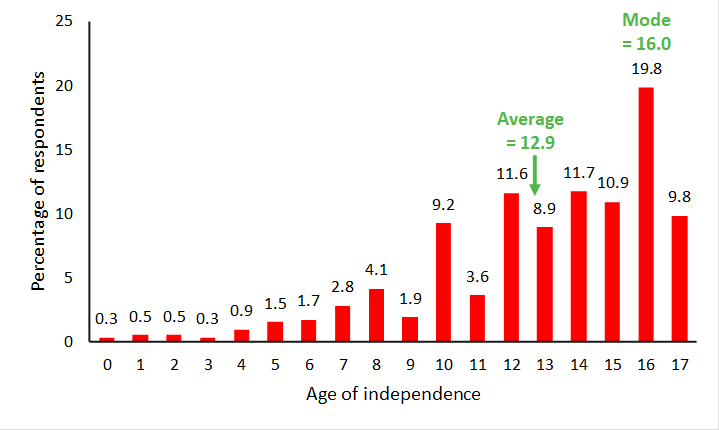

The findings showed that for parents of children aged 0-17, their average answer for the age of independence is 13 years old, perhaps because this is what they are used to. But the most common answer (i.e. the mode) is 16 years old (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Parents’ views on their child’s age of independence

Q35. “At what age do you think your child will be or was old enough to make their own decisions about the websites or apps they use?” Base: UK parents of children aged 0-17 (n=2020).

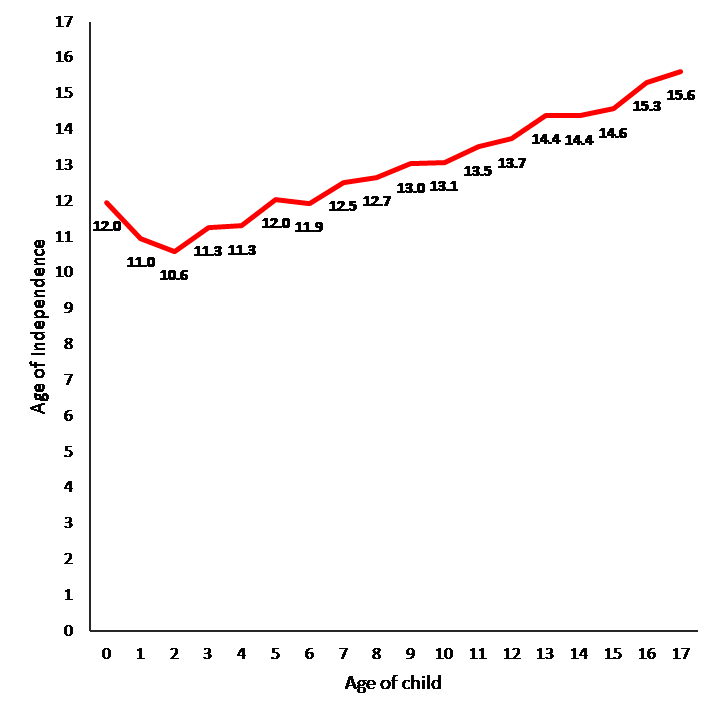

The reason for this difference between the average and mode is that parents’ views vary greatly according to the age of their child (see Figure 2). So while parents of young children consider 13 a reasonable age, parents of teenagers take a different view, clearly thinking that they should stay involved in their children’s decisions about internet use. Specifically:

- For parents of a child aged 0-9, the majority (63%) name an age of independence 13 years old or younger (averaging 11 or 12 years old, i.e. secondary school age).

- But for parents of children aged 10-12 the majority (58%) prefers an age of at least 14.

- And for parents of children aged 13-17, this majority rises to nearly four in five of parents (79%) who prefer an age of 14+ (averaging around 15 years old).

Figure 2: Parents’ views on the age of independence rise with the age of their child

Q35. “At what age do you think your child will be or was old enough to make their own decisions about the websites or apps they use?” Base: UK parents of children aged 0-17 (n=2020).

Why does this matter? Parents must trade their teens’ online opportunities against the risks

The dilemma is that if 16 is chosen, younger teenagers must rely on parental consent, potentially limiting their participation and learning opportunities. It may result in inequality (not all parents will respond attentively), deceit (teens may find workarounds) and loss of privacy (should parents know all that teens do?).

But if 13 is chosen, parents’ ability to attend to young teenagers’ online activities may be undermined, with responsibility implicitly devolved to platforms over which there are growing concerns. Perhaps oddly, there has been little policy attention to what teens are taught – is the government saying that after two years of secondary school education (in computer science? or citizenship? or PSHE?) children will be prepared to manage their data privacy? The evidence does not support this at present.

In our report on the survey findings, we further examined which parents prefer which age of independence and why.

Which parents prefer which age of independence and why?

We conducted further statistical analysis on the variation among parents in their preferred age of independence. We found that:

- More digitally skilled parents favour an older age of independence. This suggests that the more parents know about the internet, the more they are sceptical of their child’s competence to manage it (irrespective of their estimate of their children’s digital skills).

- The more parents believe that, ‘Overall, using the internet benefits children’s lives,’ the lower their preferred age of independence – presumably so children can enjoy the opportunities earlier.

- Parents who have experienced something negative online favour an older age – presumably because they too have learned about online problems. But parents who say their child has experienced something negative online favour a younger age – perhaps because if a parent knows that their child has had such an experience, they will also have seen how they coped with it, and so be confident of their future resilience.

Parents overall agree with the government that 13 is the right age. But parents of teens disagree!

Crucially, our survey findings suggest that for the parents of teenagers – who are directly affected by the new legislation – the government is setting the age of consent too young. The older their child, the older parents think their child should be before they can use the internet independently. More digitally skilled parents – who presumably understand the internet better – also think the age should be older.

So although on average, parents of 0-17 year olds think 13 is the right age, perhaps the views of parents of younger children should be taken with a pinch of salt? What matters more, surely, is that most parents of 13- to 17-year olds think 13 is too young.

If the government (and industry) want the age of 13 to meet with parents’ approval, it would be worth trying to demonstrate to them that this will bring their child more benefits than harm. And that will mean paying serious attention to the exploitation of children’s data and privacy in current debates about the wider public.

Baroness Kidron’s amendment to the Data Protection Bill, which introduced a new Age-Appropriate Design Code, offers a different approach. This will require the Information Commissioner to set standards for data processing for all online services likely to be accessed by children in accordance with the UK’s obligations as a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child – to always consider the best interests of the child, recognising their developmental needs at different ages, and their rights in the digital age.

This means that the binary question of 13 or 16 will fall away. Parents and children will no longer have to consider when their children are sufficiently ‘adult’ to cope at a prescribed age. Instead the burden of responsibility will shift to online service providers who will have to consider the needs and rights of children at all ages, including the right and needs of older children to enhanced data privacy and protection.

Notes

Methodology: See our website for the full report with data tables, the methodology and the full questionnaire.

This text was originally published on the Media Policy Project blog and has been re-posted with permission.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.