In today’s increasingly datafied society, there is mounting pressure on schools to teach children about online privacy and safety. Yet the rapid pace of technological development, regulatory changes and limited opportunities for in-service training means this is often a daunting task for teachers. In this post, Sonia Livingstone, Mariya Stoilova and Rishita Nandagiri, describe the online toolkit that they have developed to help explain to children – and their teachers – about the datafied world they live in. [Header image credit: A. Trusty, CC BY-NC 2.0]

Of the many calls on schools, one is that they should teach children about their online privacy and data, so they are ready for the challenges of today’s increasingly datafied society. Such an addition to the media education curriculum isn’t easy for schools already struggling to address e-safety, online identity and reputation, coding, information navigation, misinformation and “fake news,” digital dimensions of sex and relationships education, screen time and mindfulness, and more.

To identify what children already know, and need to know about their data and privacy online, we conducted 28 workshop-style focus group discussions with children of secondary school age (11-16 years old) and, separately, interviews with parents and educators. But although we invited children to discuss the privacy and data practices of the commercial apps and services they use, children responded in interpersonal terms, notwithstanding that institutional and commercial practices were really the issue. For example:

- Children tended to assimilate talk of data to familiar e-safety messages, not grasping the strategic or business motives driving today’s complex data ecology;

- Children talk of “the people” at Instagram or Snapchat, or a friend’s father in the tech industry, as if these ‘people’ would act like someone they know, rather than operating as a multinational company;

- Indeed, not only are they offended that “others” collect their “private” data, they also assume that those others (Instagram, for instance) would also feel it improper to collect their data;

- Extending their understanding of the interpersonal to the organisational domain, they thus expected the tactics, workarounds and deceptions which protect their privacy from friends or parents also to work with companies (e.g. giving a false name or age, or searching “incognito” or switching devices);

- We saw the extension of interpersonal expectations into commercial contexts also when things go wrong – children express frustrations about companies proving unresponsive to their reports or complaints; they would expect family or friends to respond, after all, so why not the companies?

Our research concluded that, to be agents and citizens in a digital age, children need a deeper, critical understanding of the digital environment, including its business models, uses of data and algorithms, forms of redress, commercial interests, and systems of trust and governance. Such an education may be demanding, though we believe it necessary for the fulfilment of children’s rights (along with other actions of course, notably by industry and regulators).

We also recognise that it may seem daunting to teachers, and understandably so, given the technological complexities, rapid pace of innovation, regulatory challenges and relative unaccountability of digital businesses, not to mention the crowded curriculum, limited opportunities for in-service training and many other pressures on teachers. To aid their task, we developed an online toolkit to explain to children – and their teachers – about the datafied world they live in.

Our toolkit is designed for children aged 11-16 and can be found at www.myprivacy.uk. The toolkit includes a tab for teachers – read this short brief for teachers to start with. The toolkit has several sections, seeking to answer the questions the children asked us:

- Online privacy: what’s the issue?

- Who has my data?

- Who is tracking me?

- What are my rights?

- What can go wrong?

- What do children ask for?

- How to protect my privacy?

- Where to get help?

In addition to the wealth of fun yet informative resources, we also provide a series of games, videos and quizzes. These resources have been checked out with children aged 12-15: they were tough critics, and anything dull, long, unhelpful or unappealing was quickly rejected.

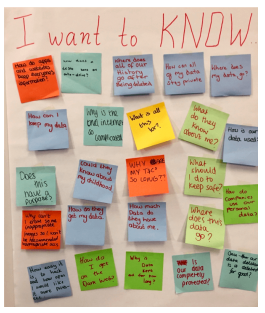

It may encourage teachers to know that children are keen to discuss the datafied world they inhabit, and they want to understand who has got their data, what is done with it, and why. As the students’ post-its about what “I want to know” illustrate clearly.

Indeed, in focus groups, children were keen to discuss the tech news they hear through the mass media – often the scandals involving the major platforms, the latest data breach or tragic suicides linked to social media, but also news about emerging innovations – smart devices, robots, and developments in artificial intelligence. The message was clear: they consider themselves the generation that will live their lives in and through technology, so they want to understand it.

During our research, we also found ourselves reflecting on the unique position of the school as an institution tasked not only with educating its students but also with managing their personal data. Couldn’t one then argue that, since the school is a microcosm of the wider society, the school’s own data protection regime could be explained to children as a deliberate pedagogical strategy? Rather than something quietly managed by the GDPR compliance officer and conveyed as a matter of administrative necessity to parents, the school’s approach to data protection could be explained to students so they could learn about the management of data that is important to them (their grades, attendance, special needs, mental health, biometrics).

Indeed, one would hope that schools would become beacons of good practice. This would demonstrate to children and parents how their privacy rights can and should be realised in the digital environment and set high expectations for institutional and commercial contexts beyond the school. It would also enliven the teaching of data and privacy literacy education for children and engender the critical citizens that a datafied world is going to need if it is not to infringe children’s – everyone’s – rights to agency, autonomy and privacy.

This article originally appeared on The Collected Learning Alliance website and has been reposted here with permission.

This article represents the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.