For a generation whose lives have become digital by default, national borders no longer represent the limits of experiences and actions. Their identities, forged through digitised representations, often develop in transnational online spaces, forming links with other parts of the world in ways that make interconnectedness an integral part of their identities and life stories. For www.parenting.digital, Christina Schachtner discusses her recent book The Narrative Subject and the online narratives of children and young people from Europe, the Middle East, and North America. Children’s online self-representations offer an insight into what moves them, their aspirations and efforts, as well as their worries and fears. Exploring children’s online narratives can help us support them to meet not only the challenges of the digital environment, but also the biographical and social challenges of growing up.

For a generation whose lives have become digital by default, national borders no longer represent the limits of experiences and actions. Their identities, forged through digitised representations, often develop in transnational online spaces, forming links with other parts of the world in ways that make interconnectedness an integral part of their identities and life stories. For www.parenting.digital, Christina Schachtner discusses her recent book The Narrative Subject and the online narratives of children and young people from Europe, the Middle East, and North America. Children’s online self-representations offer an insight into what moves them, their aspirations and efforts, as well as their worries and fears. Exploring children’s online narratives can help us support them to meet not only the challenges of the digital environment, but also the biographical and social challenges of growing up.

When we tell stories, we find ourselves; we experience and learn to understand ourselves. The online narratives of children and young people express their wishes, worries, and fears. They act as signals of their desire to be part of a community, to have a sense of belonging, to be liked and recognised. But these online stories also tell us that children are struggling to maintain clear boundaries amongst their online social networks, that they worry about being ignored, strain to manage their transition to adulthood, and dread being a failure.

The book is based on the secondary analysis of findings from the study Communicative Publics in Cyberspace, which involved children and young people aged 11 to 32 years from six European countries (Austria, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Turkey, and Ukraine), four Arab countries (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen) and the USA. The participants were invited to talk about their digital communication practices and to produce images as an answer to the questions “Who am I online?” and “When I move between different platforms, what does that look like?”. Examples of the images produced by the children are included in the text alongside their narratives – of interconnectedness, self-staging, managing boundaries, and transformation. These narratives were found in the way children spoke about their experiences, regardless of the geographic diversity, suggesting some transnationality of their self-stories.

Narratives about interconnectedness

The interconnectedness narratives express children and young people’s need for a bond, belonging, and dependable relationships, but also their fear of being alone. This is inextricably linked with social change, accompanied by the erosion of traditional social ties and increasing mobility in all areas of life, including education, relationships, and work.

“For emails, I’ll stay online all day. I check-in multiple times throughout the day”, says an American social network participant in his early 20s. An Austrian participant aged 29 years uses Facebook as a bulletin board on which he posts notes to online friends saying “Hey! I want to see you!”, then he waits “to see who’ll turn up”. Communication and interconnectedness narratives are popular amongst the participants from all countries, some describe it as “balm for the soul” triggering a feeling “like being cuddled”.

Self-staging narratives

The interviewees present their digital self-portraits in words and images, striving for that perfect representation. We live in a time in which you have to fight for visibility and to be in the spotlight. The internet affords opportunities for such self-expression: not only does it provide multimedia tools for this purpose, but it also offers the promise of global visibility. The number of followers is repeatedly mentioned in the self-staging narrations, not because it signifies friendship but because offers self-actualisation – “I am seen, therefore I am“.

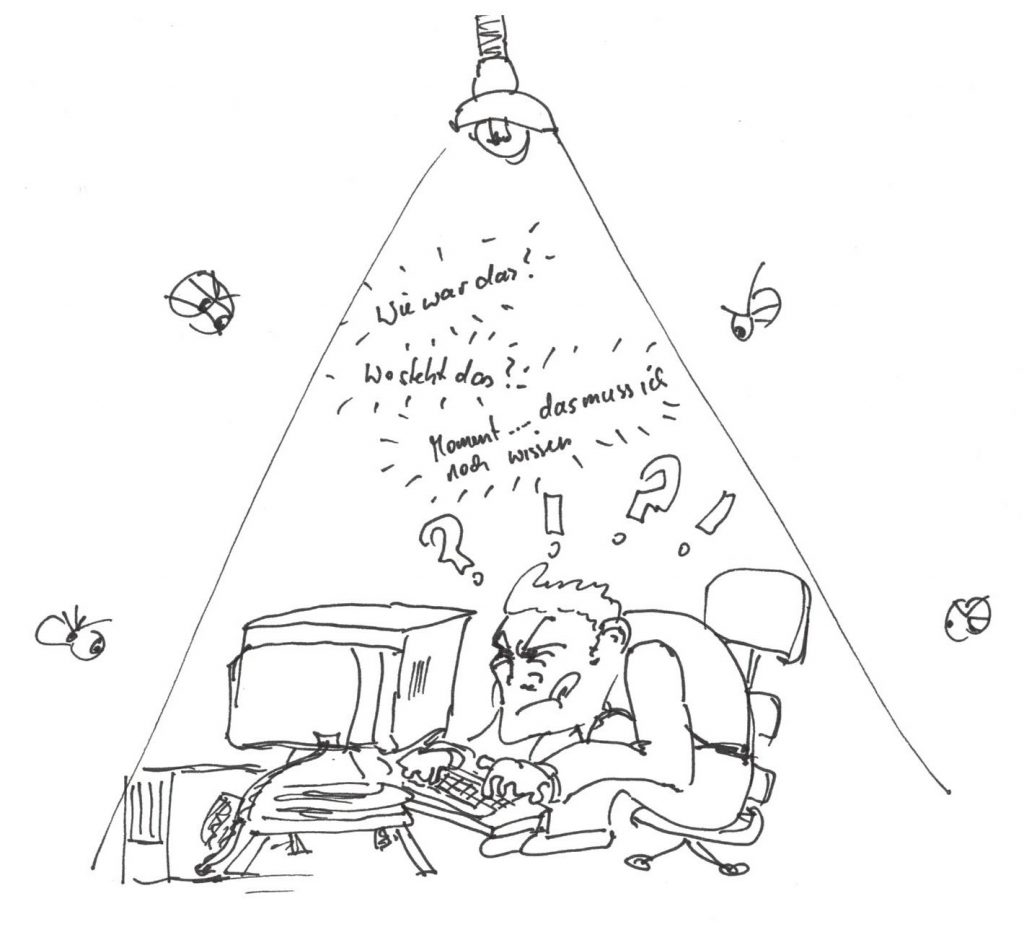

As one social media participant (29 years, Austria) admitted, if Facebook no longer existed, it would be an “absolute disaster because I enjoy showing off“. Numerous narratives are about digital self-staging on social media or blogs, like the one told by this visual image.

Based on the Japanese cartoon character Asuka, the image shows a young girl with big eyes, sensual lips, long hair, a curvy figure, and high-heel shoes. It tells of a self that wants to please by conforming to conventional and normalised ideals of female beauty.

Narratives about managing boundaries

Current social change and technological immersion are liquefying traditional boundaries, like those between “public” and “private” aspects of our lives or between virtual and offline selves. This is reflected in the narratives of the participants we spoke to. Many stories tell of episodes in which the blurring of the boundaries between public and private on the internet is deliberate but on other occasions this is unsettling. A 19-year-old girl from Austria remembers her 14-year-old self being online all day, making her entire life publicly visible. Now that prospect scares her, which she demonstrates in the image she drew. She is afraid that her online audience will gain access to her “private self” and tries to protect herself from that by being very careful about what she shares online.

In another story, a 12-year-old girl from Germany struggles with the differences between virtual and offline aspects of her life and what that division means for her understanding of authenticity. “You can’t have real friends online because their voices are missing”, she argues. Yet, she finds engaging with her internet contacts very pleasant and regrets not being able to go for ice cream together or visit the local swimming pool. The liquefying of limits is expressed in the narratives as uncertainty, scepticism, and a search for clearer or more manageable boundaries.

Transformation narratives

In the transformation narratives, the dominant theme is searching for new role models for the self that secure recognition and support personal development and growing up. This process is a challenge, as the transformation narratives reveal. An 11-year-old boy from Germany, a passionate footballer himself, follows a famous player from the national team on social media in an attempt to find out more about the lifestyle of his iodol and to copy his tricks. Asked why by the interviewer, he explains that he also wants to become famous, to be on television, and to be admired. A 12-year-old girl from Germany likes to experiment with different personas in online role-playing games: “Usually, I am a normal person and rather a girl, of course, but sometimes a boy, too“. She also organises an online drawing club which allows her to lay down rules and decide who can join. She uses the digital world not only to enact different roles but also to practise her organisational skills, leadership abilities, and assertive powers.

What can parents, teachers, and policy-makers learn from children’s online narratives?

- Children’s use of digital media should be seen as an indication of what moves them allowing parents and educators to be conversation partners, rather than to try to control these narratives and assert their authority. Providing this support requires parents and educators to be familiar with the digital world, understanding both the possibilities and the risks it affords.

- Providing children and young people with support is essential for their active and positive online engagement but also for their personal development. Parents and teachers can discuss with children their digital experiments with the self, showing interest, offering support, not imposing it. This is not only about approval as constructive critical feedback can make children feel that they are being “seen and heard”.

- Ultimately, it is a question – and this is where policy-makers come in – of creating safe online spaces for children to express themselves and participate in their online communities. It also involved preserving spaces “beyond the screen” which are attractive for children and young people and which can compete with the online world, allowing them to maintain a healthy balance between their online and offline relationships. Such efforts need to place children’s interests at the centre, ensuring that children and young people have a visible place at the heart of our societies.

- First published at www.parenting.digital, this post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- You are free to republish the text of this article under Creative Commons licence crediting www.parenting.digital and the author of the piece. Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence.

Featured image: photo by Andriyko Podilnyk on Unsplash