The internet offers many opportunities to children but in some cases, it can be associated with serious risks of harm for the most vulnerable. Monica Bulger and Patrick Burton talk about their research at a juvenile shelter in Jakarta, child trafficking and who is responsible for vulnerable teens’ well-being online. This is the fourth in a series of field dispatch reports conducted by in East Asia for UNICEF’s East Asia and Pacific Regional Office in spring of 2019. [1]

The internet offers many opportunities to children but in some cases, it can be associated with serious risks of harm for the most vulnerable. Monica Bulger and Patrick Burton talk about their research at a juvenile shelter in Jakarta, child trafficking and who is responsible for vulnerable teens’ well-being online. This is the fourth in a series of field dispatch reports conducted by in East Asia for UNICEF’s East Asia and Pacific Regional Office in spring of 2019. [1]

Warning: this blog describes first-person accounts of trafficking.

We meet in a juvenile shelter in Jakarta that houses in separate buildings victims of abuse, young offenders, and recently returned refugee child soldiers. The few windows in the room are covered with bars, the chairs comfortable though the air is stale. Ten teens ranging in age from 14-19 sit around a large table in the staff conference room. Two boys are juvenile offenders, but can’t be told apart from the victims of abuse. Apart from one boy who remains cowered and quiet, the teens seem relatively relaxed. Despite the juxtaposition of offenders and victims sharing space, they speak comfortably with each other, like any other group of teens.

They wear the same school uniform, a non-descript green jersey over white blouses for the girls, the boys wearing green sweaters despite the heat, with grey trousers and white shirts. We first discuss their app use. Residents of the shelter are not permitted to use mobile phones, so the teens first speak of what they used before. The girls lead the conversation, describing their use of Facebook and Instagram, every once in a while prompting the boys to agree or add their own anecdotes. Aside from the higher risks, these teens could be any teens, speaking about using social media to chat with friends, to meet people, to play games.

One girl stands out as being more confident than the others, speaking emphatically of her experiences. She initially speaks in broad terms of other people’s experiences, explaining that contacts online might pose as other people and give misinformation. As the questions progress, however, she offers her own example. She speaks without hesitation, intent on sharing her story. A few months before, she’d arranged to meet with someone who didn’t turn out to be who they said they were. This recalls other lighter moments speaking with students in schools where they express disappointment that people they meet don’t look as good as their pictures. In this room, however, the tone turns serious: this type of unexpected meeting seemed common for the others.

One girl stands out as being more confident than the others, speaking emphatically of her experiences. She initially speaks in broad terms of other people’s experiences, explaining that contacts online might pose as other people and give misinformation. As the questions progress, however, she offers her own example. She speaks without hesitation, intent on sharing her story. A few months before, she’d arranged to meet with someone who didn’t turn out to be who they said they were. This recalls other lighter moments speaking with students in schools where they express disappointment that people they meet don’t look as good as their pictures. In this room, however, the tone turns serious: this type of unexpected meeting seemed common for the others.

As she talks more about her experience, she shares that she’d been trafficked. In a private conversation with counsellors following the group discussion, she matter-of-factly provides details, hoping her story will prevent the same from happening to others. She’d moved from her home island to Jakarta so that she could work and send money to her family. She started work as a waitress, advertising on Facebook that she was interested in additional work. A woman contacted her and offered work in another restaurant. They agreed to meet to discuss the employment. When the girl arrived at the job interview, the woman was accompanied by a man she referred to as her partner, who was waiting in a car.

At this point, the meeting became confusing for the girl, she couldn’t recall why she agreed to get into their car. She was taken to a house where she was locked up, the following day she was taken to another island where she was locked up again and told she was going to be flown out of Indonesia. While at the airport, she managed to ask someone to borrow their phone and called for help. Her recollection of the rescue is muddled, she knows she did not board the plane and was eventually taken to the shelter.

She continues to use social media in much the same way as before, she has multiple accounts and talks to strangers online. Like other teens, she sees risk as part of using social media. Unclear is whether her experience has reduced her amount of risk-taking online.

In a later meeting, eleven counsellors, teachers, and the deputy headmistress from the shelter squeeze around the table, bringing an additional two chairs. For most of the hour, discussion is vague, translation is slow, and the discussion focuses on social media as a huge problem, lacking details. In the final 10 minutes, one social worker shares problems she’s observed at her child’s school, this prompts a few more serious examples from her colleagues. One counsellor shares the case of one of their offenders, who at age 13 met a 16-year-old boy on Facebook, met offline, and then killed him. No details are provided. The question of why a younger child would kill an older one, particularly when the older one initiated the meeting, goes unasked. Another counsellor shares that one of the victims in residence was 14 when she met someone on Facebook who invited her and her boyfriend (who was 24 and with Downs syndrome) to meet up. They were subsequently kidnapped for three days and both were raped. Eventually a friend of the girl’s family saw the girl and reported the crime to the police.

Others in the room nod, aware of the story. The mood in the room has become solemn, stories shared briefly and clinically. One 12-year-old resident met a 30-year-old man on Facebook who invited her to meet him at a bus station. At their last meeting, the man brought her to a room and raped her. After the girl became pregnant, the case was reported to the police and the girl placed in the shelter. The last case the counsellors share is that of a 16-year-old girl who was caught as part of a police sting when her aunt was trafficking her. Clearly, while the crimes have a digital dimension, neither the victims nor perpetrators are virtual. Counsellors seem overwhelmed by the harms presented by social media and prevention is not discussed.

The shelter restricts mobile phone use, but does not offer digital literacy training, which seems dangerous for the teens. Predictably, youth offenders and victims alike described continuing their social media use much in the same way as they did before. We did not ask for details about how they were accessing social media apps. One teen shared she uses the internet to meet people, creating multiple accounts so that she can “tease” those she meets, but keep herself safe. Others create fake accounts and pretend to be other people, using fake pictures. Despite the serious consequences they have experienced from their social media account, their use still feels like a game and a natural extension of teenage risk-taking and experimentation.

The shelter restricts mobile phone use, but does not offer digital literacy training, which seems dangerous for the teens. Predictably, youth offenders and victims alike described continuing their social media use much in the same way as they did before. We did not ask for details about how they were accessing social media apps. One teen shared she uses the internet to meet people, creating multiple accounts so that she can “tease” those she meets, but keep herself safe. Others create fake accounts and pretend to be other people, using fake pictures. Despite the serious consequences they have experienced from their social media account, their use still feels like a game and a natural extension of teenage risk-taking and experimentation.

The teens we spoke with had none of the traditional support and care networks such as parents or caregivers, families, or even positive peer role-models. Who is responsible for vulnerable teens’ well-being online? For vulnerable groups, more distal actors engaging in responsibly developed tech or privacy-first policies becomes an even greater priority.

The following recommendations emerged from our fieldwork:

1. Improved training for social workers and counsellors in fostering digital literacy among vulnerable children and teens would encourage conversations around device and app use, rather than outright restriction. Particularly for the teens, we spoke with at shelters, empowerment for social workers, counsellors, auxiliary protection workers, and educators in healthy engagement with contacts and content in social media use is essential for youth safety and ability to contribute positively to their communities.

2. Policy that incentivizes social media companies to act responsibly seems necessary after a decade of uneven self-regulation. The ongoing, well-documented struggles of social media companies to respond to abuse on their platforms and provide content moderation suggest a focus on profit, on expanding networks of users, without ensuring necessary safeguards as companies continue to grow on a global scale.

3. There are clear steps that social media platforms could act on quickly, specifically relating to privacy and the reduction of harms:

- Social media apps should make privacy easier, especially for young users. Social media apps can provide a layer of protection by switching much of the current public-by-default options to more privacy-protective default options, thus prioritizing user safety by design. Instead of putting the responsibility for protecting themselves on the user, social media apps should make accounts private by default.

- Social media companies should implement tools to reduce exploitative contacts, conduct, and imagery. Several social media companies have openly acknowledged that they have the knowledge and tools to reduce online harms for children, yet have failed to substantively do so. In a 2019 Financial Times article, Antigone Davis, Global Head of Safety for Facebook said they could “look at user profiles and flag someone making a series of requests to minors they do not know, or people who are part of suspicious groups…the company could also scan photographs for comments to flag patterns of bad behaviour. Other alerts could include large age gaps between people communicating privately on Messenger or Instagram Direct Messages, frequency of messaging, and people that lots of users are blocking or deleting.” Of great concern is why these fixes do not seem to have been implemented when the costs are so high for young users globally.

Through both incentivization and regulation, corporations should be strongly encouraged to proactively reduce sexual exploitation occurring on their platforms.

[1] Qualitative focus group interviews were conducted April-May 2019 in Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, Phnom Penh, and Bangkok. 301 social media users aged 11-19 participated. We aimed to include marginalised populations often excluded from this type of research: 121 of our participants were urban poor and included children with disabilities, street children, refugees, juvenile offenders, children exploited in prostitution, and survivors of sex trafficking. We conducted focus group discussions in shelters and other places of care, and in middle and secondary schools, both public and private. Recognising the importance of community and institutions in a child’s life, we interviewed 74 frontline practitioners in the region, including child psychologists and psychiatrists, social workers, counsellors, teachers, principals, and youth activists working with children. We additionally interviewed parents, grandparents, policymakers, and technology providers. Please see our report Our Lives Online: Use of Social Media by Children and Adolescents in East Asia – Opportunities, Risks and Harms for a full description of methods and findings.

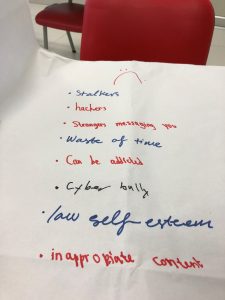

Photo credits: in-text photos by Monica Bulger: 1) Response to what bothers you about the Internet, a secondary school in Bangkok; 2) Focus group insights from teens, after school programme for street children in Jakarta.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.