In his speech to the Liberal Democrat conference, the Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg announced £120 million of new funding for mental health, pledging £40 million this year and a further £80 million in 2015-16 to end what he describes as the ‘second class treatment’ of mental health patients. Richard Layard puts the case for a ‘programme for national wellbeing’, with mental health at its core.

In his speech to the Liberal Democrat conference, the Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg announced £120 million of new funding for mental health, pledging £40 million this year and a further £80 million in 2015-16 to end what he describes as the ‘second class treatment’ of mental health patients. Richard Layard puts the case for a ‘programme for national wellbeing’, with mental health at its core.

When money is tight, policy should focus more than ever on the things that really matter to people – especially on the things that worry them most from day to day. As wellbeing research shows, their top worries are their human relationships and the mental health behind these relationships. These are things that can be affected by evidence-based public policy. If there is a proper package in this area we can do great good, and the electorate will be grateful that politicians really understand their problems. The focus should be on values and how people behave, and mental health.

Two-thirds of the electorate (and 97% of MPs) know someone with a mental health issue. But currently only a third of these mentally ill people are in treatment, and even for those on ESA it is under a half. Their families are often desperate. This situation is both unjust and a shocking economic waste.

A programme to improve values and psychological health would probably involve no net cost to the Exchequer and even its gross cost would be under £1 billion, with infinitely greater effects on our national life than any infrastructure investment of equal cost. So in this paper I suggest a set of specific policies focused on parents and young people and based on evidence guaranteeing a cost-effective outcome. The package comprises support for parents (over child behaviour, family conflict, and parenting generally), wellbeing in schools (better school discipline, better values, and better life skills), better mental health (improved access to psychological therapy, waiting time targets, and a CAMHS worker in every school), and better job prospects (our apprenticeship guarantee and job guarantee).

Background

We can begin with a striking fact. Suppose we divide the whole adult British population into those who are most miserable (the quarter who are least satisfied with their lives) and the rest. We can then ask, what factors best explain which people are miserable? Here are the weights attaching to four of the most important factors:

- Mental health (0.22)

- Physical illness (0.15)

- Poverty (0.06)

- Unemployment (0.04)

There are two reasons why mental health matters so much. One is that 6 million people have diagnosable mental illness – twice as many as are unemployed. The other is the damage which it can cause, including broken families, chaotic children, and disability and welfare dependence.

Here is another fact, this time about children aged 10-15. They were asked, ‘how do you feel about your life as a whole?’. Their reply was heavily influenced by whether they were from a broken family and by whether other children misbehave in school – but very little by the income per head in the family. Much other evidence (such as in this 2012 Office for National Statistics report on wellbeing data from the Annual Population Survey) confirms the huge importance of other factors, as compared with family income. In fact, family income per head only explains 1 per cent of the variation in life-satisfaction across the British population.

The conclusion must be that if we want to help the deprived, we need a much wider concept of deprivation. You are as deprived if you have enough but cannot enjoy your life as if you do not have enough. So we need to help people achieve satisfying relationships (including work) as much as we help them with money. This is also good politics since there are people in every social class whose lives are ruined by chaotic relationships, depression and crippling anxiety, who would be delighted to hear politicians talking about these things. So let me outline a possible evidence-based package, and show how little it would cost.

1) Support for parents

- Badly-behaved children. If children have moderate or mild conduct disorder, the Webster-Stratton programme of group training for parents produces sustained improvement in 2/3 of the children. It should be available free to all parents who need it. This requires further expansion of existing provision.

- Family conflict. “Behavioural couples therapy” is recommended by NICE for parents in conflict. It is hardly available anywhere in the NHS. We should propose a programme for roll-out.

- Parenting classes. Parenting classes should include not only childbirth and physical care but also the emotional relationship with the child and the impact of parenting on the relationship between the parents. We should develop an NHS-coordinated programme that offers such classes free to all parents. There could be little more important to do than this.

2) Wellbeing in schools

- School discipline. Over 40% of children say that other children are ‘always’ or ‘often’ so noisy that they find it difficult to work, according to a 2008 National Union of Teachers report. But there are well-tested Webster-Stratton programmes for training teachers to control behaviour, based on the same principles as parent training. They should be part of standard teacher training, and available to serving teachers who want to take them.

- Values. We need schools to be as concerned with character as with competence. A respectful, altruistic ethos is successfully cultivated in “values schools”. We need to identify with this and similar movements, as before 1997 we identified with the literacy movement. Every school should have a Wellbeing Policy, which includes mental health awareness. All research shows that happier children learn better. Academic results and personal wellbeing are not rivals, as DfE currently believe, but complements.

- PSHE/Resilience. PSHE should become statutory. But we also need a development programme to improve the teaching of it, using existing evidence-based methods (including evidence-based teaching on parenting). PSHE should become a specialism in the PGCE.

3) Mental Illness

Nearly 1 million children and young people and 6 million adults are mentally ill. The Health and Social Care Act promises parity of esteem for mental and physical health. But less than a third of mentally ill people are in treatment. This is true of children and adults, and is mainly due to lack of facilities. Moreover, there are no waiting time targets for psychological therapy. It is a disgrace and a new deal is required in which treatment is as available for mental illness as it is for physical illness.

- Parity of esteem. NICE-recommended psychological therapies should be available to all who need them.The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme which was launched in 2008 has, according to Nature,set a world-beating standard and has over 45% recovery rates. But it only reaches 10% of adults with depression and anxiety. A good objective for 2020 would be 25% of adults and 40% of children (25% now) with 50% recovery rates.

- Waiting times. There should be a 28-day waiting time limit for psychological therapy, given the urgency of the need.

- CAMHS .Every school should have a named (part-time) therapist working in it (on outreach from CAMHS).

4) Better Job Prospects

An essential feature of a good society is that young people feel they are wanted, and have a natural way in which they can contribute to society. There are two excellent policies for this:

- The apprenticeship guarantee for 16-19 year olds. This was in the 2009 Act but the guarantee was repealed in 2011. It should be reactivated.

- The job guarantee. This should guarantee every unemployed youngster a job within 12 months – and remove the option of continued life on benefits.

Cost

There is good evidence that most of the above proposals would have no net cost to the Exchequer. For adult mental health, there is good evidence that within 2 years, the Exchequer cost is recovered twice over, through savings in physical healthcare, and savings in benefits and lost taxes (mental illness is 40% of disability). For child mental health, the savings take longer to accrue but there is good evidence that once again they exceed the cost, according to a 2008 Department of Health report. The same is true of resilience training in schools, where the gross cost is very small since it fits within the existing timetable.

Better school discipline and values yield savings which are harder to measure. But the gross cost of the proposals is small. The apprenticeship guarantee is supported by the evidence of a 40% rate of return to apprenticeship – much of which goes to boost tax receipts. The job guarantee is estimated to recover about half its cost in savings on benefits and lost taxes.

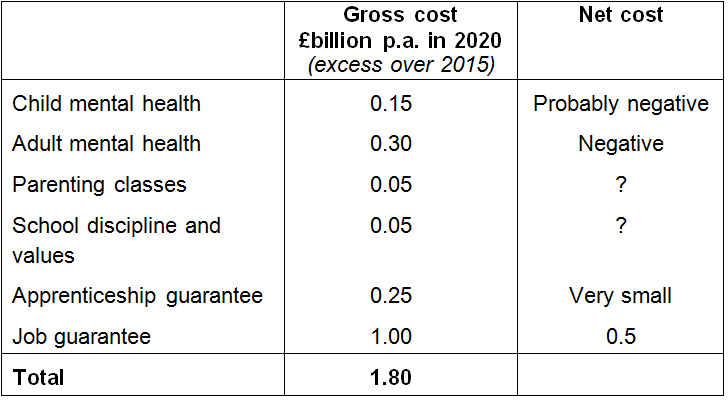

The gross cost of these proposals (before deducting savings) would need some work but may be of the order shown in the table below. The low cost of the first four rows is striking, when one considers their transformative potential for people’s lives and the daily worry that these issues cause.

Table 1: possible costs of national wellbeing programme

The happiness of our community depends, more than anything else, on how people behave. This in turn depends on their values and their mental health. We can no longer treat these issues as marginal. There are professional ways in which they can be addressed. How they are packaged is for politicians to decide, but obvious possibilities include a Wellbeing Programme, or a Charter for Parents and Young People, or 5 Pledges. Five possible pledges are: free professional support for parents with a difficult child, in family conflict or wanting parenting advice; free professional help with depression and anxiety (including post-natal depression) within 28 days; specific training for teachers wishing to improve their class control or to teach life skills; an apprenticeship for every young person who wants one and has any GCSEs; and, a job for every young person within 6 months of looking, with no option of life on benefits.

However it is done, politicians need to show the electorate that they know what worries them, and have specific, costed ideas about how to help them.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: ‘Silhouettes – Wellbeing Space’, Joe Flintham, CC BY ND 2.0.

Richard Layard is Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics, programme director of the Centre for Economic Performance, and a Labour life peer in the House of Lords. He is a labour economist who has worked for most of his life on how to reduce unemployment and inequality. He is also one of the first economists to have worked on happiness, and his main current interest is in how better mental health could improve our social and economic life. He is the author of many books, including Happiness: Lessons from a New Science and Thrive: The Power of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies, his latest book co-authored with David Clark.

Richard Layard is Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics, programme director of the Centre for Economic Performance, and a Labour life peer in the House of Lords. He is a labour economist who has worked for most of his life on how to reduce unemployment and inequality. He is also one of the first economists to have worked on happiness, and his main current interest is in how better mental health could improve our social and economic life. He is the author of many books, including Happiness: Lessons from a New Science and Thrive: The Power of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies, his latest book co-authored with David Clark.

1 Comments