Peter Jefferys argues for building affordable social homes and reforming the private rented sector. He makes the case that lower rent is vital for economic recovery, stating, if average rents in England had risen at the rate of inflation since 2000, rather than well above, then renters would have an extra £8 billion per year of disposable income.

Peter Jefferys argues for building affordable social homes and reforming the private rented sector. He makes the case that lower rent is vital for economic recovery, stating, if average rents in England had risen at the rate of inflation since 2000, rather than well above, then renters would have an extra £8 billion per year of disposable income.

High rents for private tenants are increasingly a politically salient issue, especially in high-demand areas such as London and the South East. Private tenants feel trapped between expensive renting and unaffordable mortgages, with banks still demanding much higher deposits than before the financial crisis. While this trap is frustrating for those who want to buy and devastating for low-income families with no other options, it may also be having an impact on economic recovery.

Renters are increasingly paying more in housing costs than those buying a property with a mortgage. For some low-income renters, especially in London, the proportion of their wage going towards rent can be over 70%.

We have collected evidence that these costs and uncertainties mean that renters are cutting back their spending on consumer goods and services. Increasing numbers are relying on high-cost credit to make up the shortfall, entailing high cost repayments and deferred spending cuts.

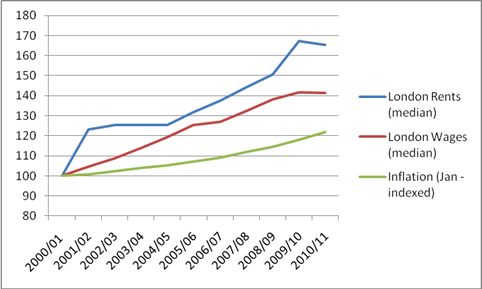

As the chart below shows, the cumulative gap between rents and wages was growing in London before the financial crisis but post-crisis it has grown even wider. Coupled with falling household incomes this means that rents are eating up even more disposable income.

London rents and wages (source ONS, DCLG)

Many economists say that we face a demand crisis. There simply isn’t enough spending in shops and on British products to get people back into work. Given that there are 8.5 million renters in England (including 1 in 4 Londoners) and in the capital renters pay on average between 42 and 46% of their wage in rent, there is a strong case that a lot of potential consumer spending is being lost.

But doesn’t the rent we pay go back into the economy anyway? There is a strong argument that a lot of it doesn’t.

The majority of landlords are individuals or couples renting out just one or two homes. Many of those landlords are using the rents to pay off their mortgages and make a small yield. A huge amount of money paid in rent is not re-circulating into the economy, but rather it is financing mortgage debt. If banks were re-lending this money, again it might not be a problem. But, as we’re constantly hearing – bank lending has dropped massively since 2008.

Equally, even if all rent went straight into the pockets of landlords there would still be a case that this is reducing spending in the economy. Higher earners spend proportionately less of their income compared to lower earners and on average landlords have higher incomes.

Astonishingly, if average rents in England had risen at the rate of inflation since 2000, rather than well above inflation, then renters would have an extra £8 billion per year of disposable income, or more than £2000 extra per household per year (Figures from the English Housing Survey and ONS). That would have meant far more going directly into the pockets of lower earners to be spent in the economy than Labour’s proposed VAT cut (which would cost the Treasury £12bn per year).

There is also the crucial point that high private rents increase the housing benefit bill, which currently costs the government more than £20bn per year (having doubled over the last decade). In a recent report we set out how the balance of government spending on housing has shifted from spending on house building to spending on housing benefits. Our analysis shows that if just 8% of private rented tenants moved to affordable social homes the government would recover £200 million in savings.

How then might we overcome the economic drag of high rents? Shifting the balance of government subsidies towards increasing the supply of affordable homes is an issue we explore in detail in our report Bricks or Benefits?. Building more affordable social homes has the double advantage of reducing pressure on the overheated private rented sector and increasing spending power dramatically for those families who do get into social rented homes.

Equally, reform of the private rented itself is long overdue. A major new Shelter report, published last week, makes the case for five year, inflation linked tenancies with two month break clauses for tenants. The benefits of this model include stability for renting families, more disposable income over the long term and are even beneficially for landlords’ business models.

By building affordable social homes and reforming the private rented sector we would certainly be helping millions of families who are struggling with the third highest housing costs in Europe. We would also be putting cash into people’s pockets to sustain an increase in consumer demand that is reliant neither on personal debt nor expensive tax cuts.

Author’s note: 3.62 million renting households in 2010/11 would be paying on average just £95 rent per week if the median £78 per week average rent from 2000/01 had risen with CPI inflation, rather than the actual 2010/11 median figure of £137 per week. Across England this equates to £7.9 billion extra rent paid per year. The difference between £95 and £137 is £42, so on average a renting family would have £42 per week extra disposable income, or £2184 per year.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Pete Jefferys is in the policy team at Shelter. Before joining Shelter, Pete worked for the Co-operative Party and the Labour Party as well as on climate change policy in the civil service.

Yes forced onto second class citizenship, I am a quite capable person who is in difficult times at the moment. It suits my family responsibilities to work 30 hours a week at the moment in a low paid job. With working tax and child benefit I really should be doing ok and able to progress in life. However I find myself constantly Short of money despite minimising spending. My biggest worry is that I will now remain trapped in this lifestyle forever. A friend of mine was recently bemoaning how it is difficult for her to manage on a salary of £27000 a year; when I was on £20000 last in 2004 I was pretty flush, how times have changed.

This is completely true I’m my case. 70% of my income goes to my landlord.

I think the comments on this post are just as interesting as the article itself. Luke is a perfect example of someone that is disillusioned by the property market and wages in London. Without an affordable rent people are choosing not to go out and spend money; making them feel depressed. If rent inflated at the same rate as wages more money would be available to re-invest into the economy. Currently the average home costs more than 6 times the average income.

The Shelter Report’s proposal for 5 year tenancies is interesting and realistic. At the moment there are yawning chasms between lifelong, subsidised social tenancies, highly insecure 6 month Assured Shortholds and buying with a mortgage. The average length of time homeowners stay in one property is around 5 years so even achieving the holy grail of saving a deposit and getting a mortgage isn’t perfectly suited to the way we live – in a downturn houses are difficult to sell and so can trap people. However, I think the report could be bolder in bridging the gaps between the three currently dominant models for getting a home.

http://botzarelli.wordpress.com/2011/11/22/middlehold-how-to-make-the-housing-market-work-better/

I represent the feelings of many many people in Social Housing & also those waiting for Social Housing who are feeling an almost enforced “Second Class” citizenship in this country.

We have no help (just the “benefits” that everyone assumes we all get & want & need, which is not the case).

We are not covered by the same laws, we do not receive the same treatment & we certainly do not feel appreciated as we should, as many of us do the lower paid jobs that are essential to a well balanced society.

Please read my blog / visit my Facebook page .

We are fighting for some help. NOT more Benefits – THE MAJORITY OF US DO NOT WANT THAT AT ALL, WE CAN SEE IT DOESN’T WORK!

http://s0ciallyh0used.wordpress.com/2012/10/02/its-just-not-working/

Interesting analysis. In addition it seems to me that housing benefit for employed people will often end up as subsidy to corporations. To take an extreme example, if Goldman Sachs pay their janitors 20,000 a year, but this is supplemented with 20,000 year housing benefit than Goldman Sachs is the actual benificiary. Janitors are essential to their business so that Goldman Sach would have had to, and would have been able to, pay 40,000 if housing benefit had not been available.

Difficult to get actual numbers on how much this subsidy is in total, but my rough calculations suggest it’s around 4 billion. I guess that this then distorts the market in London in particular, making it cheaper than it should be to operate out of the capltal.

The first graph grossly underestimates the effect of rent increases on the poor, namely as it uses ‘average’ rent prices and ‘average wages’. The data is too highly aggregated to understand the disparity between the wages of the poorest and rent increases. To make this clearer, the wages of someone working the financial sector have been aggregated with a check-out assistant in Tesco. We are able to learn little about the relation between rent prices and the wages of the poor. Maybe some purposive sampling should be done on shop-assistants (for example, supermarket check-out workers), call centre workers and other typical jobs of the working poor. This would fill in gaps in the current data and capture both labour-market heterogeneity, and the experiences of the poorest in the rental sector.

On another note, there needs to be an acknowledgement that the poorest in the rental sector are there to stay. Affordable housing is unlikely to be of benefit them. Maybe we should start looking beyond first-time buyers and aim to help the actual poor through private rental sector regulation (of which this article rightly argues). Maybe this could be done through attaching rent price increases to the minimum wage. For the moment, this is politically of the cards.

Do not forget that 85% of new builds in London are purchased by foreigners. Many of whom rent out their ‘investments’. The rent, UK private sector of the Economy money, then dribbles out to various exotic destinations. Housing benefit, UK public sector economy money, follows along as well. My own rent vanishes into a Cyprus company. (For the inaware, Cyprus is a large offshore zone frequented my Russians). In fact my neighbours also rent and their monthly payments whizz off to the BVI.

Not tax domiciled individuals of companies should not be allowed to purchase our national housing stock.

Thank you, an excellent article. How about a follow-up piece on the case for land value taxation? Surely that’s the ultimate way of reorientating our economy away from the rentier and landowner classes, who have rigged all the legislation in their favour for many many years and have all the main political parties in their pocket.

An interesting read, but really its detailing the obvious: we’ve just had a property bubble and are just starting to realise how toxic it really all was and is. We can’t all become rich by selling property to each other to infinity and you have to wonder what the state of the economy would be if we had invested even a small proportion of the paper equity locked up in property.

House prices are effective debt slavery – how can someone in their working life manage to a. pay living costs, b. fund their pension (and that of baby boomers), c. pay off a house on todays prices? So thank you for raising this, I agree it is a massive problem, not only impacting consumption, but also putting pressure on wages to rise, damaging the competitiveness of UK labour. Government argues all too easily that building needs to increase, but that ignores that prices rises correlate most closely with increases in the money supply with ever larger mortgage multiples and unfeasibly low interest rates. Some economists argue that faling house prices would destroy wealth, whilst others have said it merely shifts wealth from one generation to the other. It would be interesting to see what you think, and if the LSE can help shift the debate from ‘give the builders all they want’ to ‘maybe house prices do need a correction.’

My Rents take 68% of my income then I have council tax energy bills to pay, leaves me with very little to save. I don’t think i can continue like this working for nothing, we hear about affordable rents which to me is rubbish, i’ve look at social rents and since new government laws to adjust housing associations rents with market rents for example noe they what £240 a week for a one bedroom flat and thats is supposed to be affordable.

The money some on housing benefits could be used to build more social homes with cheaper rents.

Yes, my spending has dropped, I dont see the point in spending like i used too, and this is coming from a person that has not debt apart from a student loan. If the government wants me to spend then they must fullfill there side and build more social homes in London.

I have thought about moving to Asia or the US for work britain rents are just to expensive and my Skills are valued in those countries, and I have started to look.

The long term unemployed are financially savvy and understand whats really happening, there is no motivation for working because that motivation has been taken by high rents, and this economy will never recover and be as competitive.

When you look at the real causes behind rental prices it really is no wonder this conclusion is reached. The Buy to Let market is being perpetuated by the lending industry, claiming demand is high and will continue to rise – the flaw is that wages are not. Whilst Buy to Let is reported to be helping, and under certain circumstances it is – the banks promoting it as an easy investment and continuing to lend money they don’t have, to people they have convinced that it is the next big thing and the answer to the housing crisis is only going to make the problem worse. More in depth: http://www.ipinglobal.com/ipin-live/406237/residential-buy-to-let-funding-and-financial-incest

Revised Q2 UK GDP figures out today show imputed rent now makes up 8% of it up from 6% in 2007. This is the rental value of houses not let.

http://www.gscape.com/images/econ/charts/ImputedRentQ22012.gif

Rents now makes up 11.3% of UK GDP a new record.

High rents and imputed rent are being used to boost our GDP and so bring down our debt to GDP ratio, while in reality it destroys the economy by allowing the rentier class to suck up more disposable income.