David Cameron recently unveiled a £200 billion public-private partnership aimed at improving Britain’s transport, energy and technology infrastructure. And many interests in the Tory party look forward to the coalition bringing forward major government asset sales. Looking back to 2006, Andrew Massey and Gil Shidlo investigate how the Labour government’s privatisation of UK defence agency QinetiQ generated fantastic rates of return for a few top executives and a private equity fund (the Carlyle Group). They link this fiasco to the private equity fund tradition of paying lower salaries in order to incentivise executives to achieve share price growth. This case highlights the need for future public-private deals to undergo much more rigorous scrutiny, covering the total remuneration of PPP companies and top executives.

David Cameron recently unveiled a £200 billion public-private partnership aimed at improving Britain’s transport, energy and technology infrastructure. And many interests in the Tory party look forward to the coalition bringing forward major government asset sales. Looking back to 2006, Andrew Massey and Gil Shidlo investigate how the Labour government’s privatisation of UK defence agency QinetiQ generated fantastic rates of return for a few top executives and a private equity fund (the Carlyle Group). They link this fiasco to the private equity fund tradition of paying lower salaries in order to incentivise executives to achieve share price growth. This case highlights the need for future public-private deals to undergo much more rigorous scrutiny, covering the total remuneration of PPP companies and top executives.

The sale of the UK Ministry of Defence’s research wing QinetiQ in 2006 created a media sensation amid reports that a number of top civil servants earned millions of pounds and perhaps cut taxpayers short. Our first Table below shows that indeed four top executives invested tens of thousands of pounds in the new company, and all became instant multi-millionaires after the flotation saw the company’ share prices spiral immediately upon its launch.

| Executive | Personally invested in flotation £ thousands | Value of personal shares after flotation £ thousands | Percent Return on Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sir John Chisholm (Chairman) | 130 | 25,970 | 19900% |

| Graham Love (Chief Executive) | 111 | 21,350 | |

| Hal Kruth (Group Commercial Manager) | 70 | 13,880 | |

| Brenda Jones (Marketing Director) | 60 | 11,180 |

Source: NAO (2007).

By looking more closely at the roles and motivations of key managers and non-governmental players involved we hoped to better understand the way that national assets are deployed and how those entrusted with leading them are constrained to act in more transparent and accountable manner.

The creation of defence technology company QinetiQ in 2001 signalled a new phase in public-private partnerships (PPPs) by moving private equity into the heart of Britain’s defence establishment. The move towards more PPPs, was a core aspect of the Blair/Brown modernization programme in which public assets were rapidly offloaded in order to meet policy targets and raise revenue quickly; a follow-on from the ‘Next Step Programme’ which evolved as a major aspect in central government’s attempt in the 1980s and 1990s to deliver more efficient and effective public services..

The company was formed when the UK’s Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) Defence Evaluation and Research Agency was divided into two separate entities; QinetiQ plc, a wholly government-owned company, and a smaller Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (which still remains part of the MoD). In 2002 the Labour minister Lord Lewis Moonie (then an under-secretary of state at the MoD) stated that although QinetiQ was being prepared for a public-private partnership it would remain a British company based in the UK and that the MoD would ‘retain a special share in the company to ensure that the nation’s defence and security interests continue to be protected.’ In 2003 the US-based private equity firm Carlyle Group purchased a stake in the company and QinetiQ was eventually floated was floated on the London Stock Exchange in February 2006.

MoD remained a shareholder in QinetiQ until 2009 when Labour ministers decided that the MOD should sell off its remaining shares, to raise a great deal of desperately needed hard cash. This was an unprecedented and highly controversial move in the defence sector. Not only did the sale remove defence research potential from UK state control, but it raised serious accountability issues as the new owners were an overseas private equity fund and not a publicly listed company.

In a 2007 report, the National Audit Office examined the 2006 privatization of QinetiQ, the manner in which it was sold and its impact on taxpayers. Their report criticised the large returns by the top management of QinetiQ on their initial investment detailed above. It also looked closely at why and how the MoD came to approve the structure of the Carlyle scheme. The NAO report raised two interesting components of the sale; firstly, the 20 per cent allocation of equity to management and staff and greater rewards for senior management, and secondly, the involvement of QinetiQ’s own management team’s in settling their own remuneration.

The NAO also examined the purchase of equity by the management – which is a widely exercised practise in similar cases – and the performance ratchet which increased the shareholding by management as certain thresholds of performance were achieved. But the NAO report failed to fully explain the actions of the MoD and the government in the QinetiQ sale. Rather it simply suggests that it was in line with the rapid off-floatation of public assets in order to meet policy targets and to quickly raise revenue.

Our research has uncovered some of the gaps in the NAO’s investigation, such as their lack of attention to the salary component of the company’s top management remuneration. We found that in the USA private equity executives generally have lower salaries than executives in publicly quoted companies, because private equity firms want to keep compensation costs down and to rather award managers only for increasing performance on the stock market. An interesting trend is that once the companies taken over by private equity become public companies again, the variance in pay plus stock compensation begins to converge towards the public companies norm.

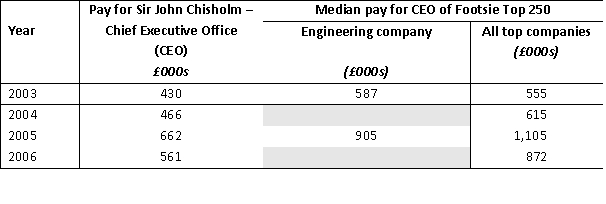

Looking at the pre-privatization period (2003 to 2006), it is apparent from our second and third Tables below that the top two QinetiQ leaders were not being radically over-paid by comparison with other FTSE Top 250 companies in this period. Indeed Sir John Chisholm was generally paid considerably below the levels being paid in comparable companies in this period, and below the salaries of CEOs in FTSE top 250 engineering companies.

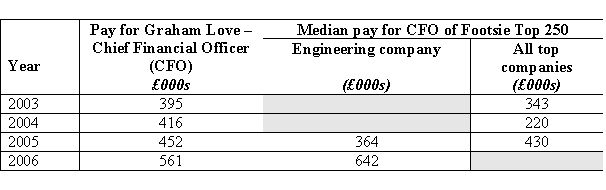

Graham Love as Chief Financial Officer, was generally paid somewhat above the average for other comparable companies, although not in the flotation year of 2006.

It is not clear why the company’s top two executives were treated in these somewhat different ways. But given the sky-high remuneration levels of these boom years in the private sector, UK policy-makers may have been lulled into a false sense that the QinetiQ executives were exercising restraint – when they were in fact just setting the company up for post-privatization share price.

We decided to extend our research and looked at the pay of QinetiQ managers after QinetiQ was listed in the London Stock Exchange. Would QinetiQ follow the same trend as US companies in that the compensation difference between QinetiQ and FTSE 250 listed companies would converge? Sir John Chisholm’s salary is still below the median for similar FTSE companies, while the Chief Financial Officer is still above the median for comparable companies, but less so than was the case before privatization.

From work carried out in the US we found that that CEOs can legitimately influence the terms of a sale of their companies to private equity by withholding positive information from directors and shareholders about the value of the firm before the sale. By doing so CEOs can cause directors and shareholders to sell the company to private equity for less than it’s worth. We stress that although there is no such evidence for any of these occurrences in the sale of QinetiQ to Carlyle it is important that audit authorities should properly scrutinise privatization and PPPs to ensure that these activities do not take place.

This blog summarizes a longer article, A. Massey and G. Shidlo, ‘Privatization, private equity and executive remuneration: Privatizing QinetiQ’, Public Money and Management, November 2010, pp. 339-46.

1 Comments