In the first of two posts examining the Alternative vote, Alan Renwick from the University of Reading looks at how the AV electoral system may affect election results at both the local and the national level. In this first post, he gives a simple guide to how second preferences are re-allocated, examines whether AV will only allow majority winners at the constituency level, and whether this electoral change will do away with ‘one person, one vote’.

In the first of two posts examining the Alternative vote, Alan Renwick from the University of Reading looks at how the AV electoral system may affect election results at both the local and the national level. In this first post, he gives a simple guide to how second preferences are re-allocated, examines whether AV will only allow majority winners at the constituency level, and whether this electoral change will do away with ‘one person, one vote’.

The effects of a change in the voting system could be wide-ranging. Despite the attempts of many pollsters and academics, it is impossible to predict with certainty how the British voter would change their behaviour if allowed to indicate preferences instead of picking only one candidate. However, it is possible to look at the evidence behind some of the arguments used on both sides of the AV debate. We begin by looking at how votes will be counted under the Alternative Vote.

How votes count under AV

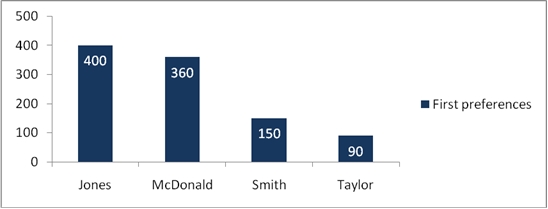

Imagine an election with four candidates. 1000 valid votes are cast, so a candidate needs 501 votes to win. The first preferences for each candidate are as follows:

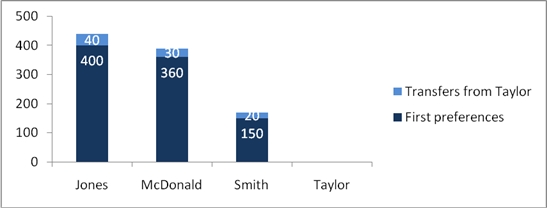

In a First Past the Post election, Jones would be elected with 40 per cent of the vote. But that is not what happens under AV. No one has passed the 50 per cent mark, so the bottom candidate (Taylor) is eliminated. In the second round of counting, the first-preference votes for Jones, McDonald, and Smith all still count as one vote each. The votes cast for Taylor also still count as one vote each, but now they count for the candidate that these voters ranked second, not for Taylor.

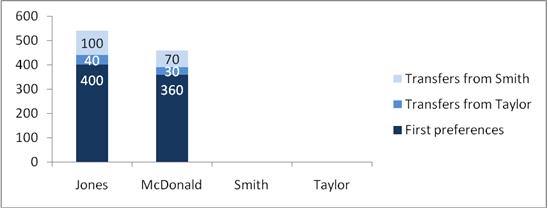

Still no one has gained an absolute majority. Now Smith is eliminated, with Smith’s voters’ second preferences going to Jones and McDonald, as well as some third preferences from Taylor’s supporters going to both candidates. Again, everyone’s vote counts as one vote, for whichever of the remaining two candidates is ranked higher by the voter. Jones is preferred by more voters than McDonald and is therefore elected by 540 votes to 460.

The claim that AV gives some voters extra votes is a fallacy

Many supporters of FPTP have argued that AV gives some voters extra votes. This is wrong. Under AV, each voter’s vote has exactly the same value.

In the first round of counting, everyone’s first preference is counted as one vote. In the second round, if your favourite candidate is still in the race, your first preference still counts for one vote. If your favourite candidate was eliminated, your first preference now counts for zero but your second preference counts for one vote. From each ballot paper, only one vote is being counted. This remains true at each stage of the counting process. The example above shows how this works in practice.

AV and majority winners

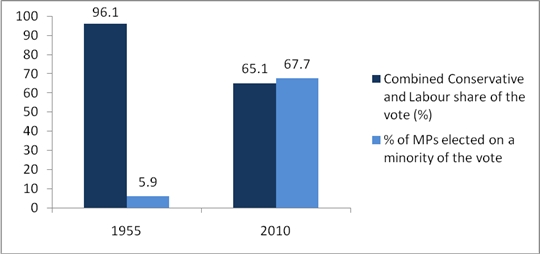

First past the post (FPTP)’s opponents complain that it allows many MPs to be elected on a minority of the votes: in 2010, only 210 out of the 650 elected MPs secured 50 per cent of the vote or more in their constituency. As the Figure below shows, the number of minority winners has risen enormously since 1955, when 94 per cent of all MPs secured an absolute majority. The change has occurred because votes are much more spread out across parties today than they were in the early post-war decades. AV supporters claim that more citizens would feel a connection to their MP if more had voted for them. They also suggest that this would improve legitimacy.

The 1955 and 2010 elections compared

AV would indeed increase the number of MPs elected on a majority vote. But three provisos are needed. First, some minority winners would remain. Because the proposed version of AV does not require voters to rank all candidates, some will express preferences only for candidates who are eliminated in the early stages of the count. It will therefore sometimes be the case that neither of the last two candidates in the race secures an absolute majority.

In state-level elections in New South Wales and Queensland – where voters are allowed to rank as many candidates as they wish – the proportion of constituencies with minority winners has ranged from just 1 per cent to 31 per cent in elections since the early 1980s. In the 32 Scottish local authority by-elections held using AV since 1997, twelve – just under 40 per cent – have produced minority winners.

Second, some of the votes in the majority block might be quite low preferences. Whether such votes are seen as enhancing an MP’s legitimacy will depend on how widely it is accepted that they should matter.

Third, there is little evidence that minority winners are widely seen as illegitimate. Few voters know the details of their constituency election result: fewer than half can even correctly name their MP. Focus groups suggest that many voters do not even realize that minority victories are possible. This suggests that whether their MP secured an absolute majority or not is unlikely to make much difference to many voters.

The weighting of higher and lower preferences

Another concern (often muddled with the extra votes fallacy, but actually quite different) is that AV gives higher and lower preferences equal weight: it treats a sixth preference as one vote just as it does a first preference.

This is true in a sense: when a sixth preference is counted, it is given the same weight as a first preference. In the example shown above, the second preferences of voters who originally favoured Taylor are given the same weight as the first preferences of the supporters of Jones and McDonald. In another sense, however, it is not true: AV gives extra weight to higher preferences by counting them first. A candidate may be the second choice of most voters, but if he does not capture a decent share of first preferences, he will be eliminated from the race before this broad support can be tapped.

So how should preferences be weighted? One view is that our first preference captures something special – our core belief – and should therefore carry special weight. Another view is that we cannot make such presumptions about the structure of people’s preferences. Some voters might want someone from the right instead of someone from the left, but not be so concerned about which right-wing candidate they get. Some voters find it very difficult to decide their first preference but are very clear about some of the candidates they don’t want.

There is therefore no clear basis for discounting lower preferences completely. But there is legitimate debate over whether AV (or any electoral system) gets the balance right.

AV, in an important sense, is more likely than FPTP to elect the candidate with broadest support

Under FPTP, how well a candidate does depends partly on how popular he or she is and partly on how many other similar candidates are running in the constituency. In a constituency with one left-wing candidate and three right-wing candidates, the left-wing candidate could win even if right-wing voters are in the majority because the right-wing vote splits.

AV is designed to prevent such outcomes. It allows the right-wing voters to coalesce around the most popular right-wing candidate and secure the seat. Thus, in such scenarios, provided we are happy to treat lower preferences as meaningful, AV is more likely than FPTP to elect the candidate with broadest support.

A point to stress though is that the number of occasions on which AV produces a different result at constituency level from FPTP is likely to be low. The British Election Study team estimate that AV would have produced a different result in the 2010 election in 43 seats – fewer than 7 per cent of the total. Similarly, in Australia, the number of seats in which the ultimate winner has not led on first preferences has been between 5 and 7 per cent in each of the last three elections. My second post later this week will examine this in greater detail.

This article has been adapted from Alan Renwick’s paper The Alternative Vote: A Briefing Paper

Please read our comments policy before commenting.