Evan Williams presents evidence showing that benefit sanctions lead to increases in claimants’ anxiety and depression, and argues that a re-assessment of the role of sanctions is needed as the UK slowly emerges from lockdown.

Evan Williams presents evidence showing that benefit sanctions lead to increases in claimants’ anxiety and depression, and argues that a re-assessment of the role of sanctions is needed as the UK slowly emerges from lockdown.

In response to enduring high unemployment after the 2008 financial crisis, the Coalition Government (2010-15) relied on a ‘massive campaign of sanctions‘ to reduce benefit rolls. This response paid scant regard to the actual availability of jobs in the economy and is unlikely to be effective in lowering unemployment in the current context, where the number of people claiming Universal Credit has dramatically increased in the wake of COVID-19. While work search and work availability requirements for claimants – and their enforcement with benefit sanctions – were suspended for three months in March 2020, the jury is out on whether this leniency will continue as the lockdown restrictions are being lifted. What the jury is also out on is whether any lessons have been learnt from recent developments in sanctions policy.

Benefit sanctions and impacts on mental health

Sanctions policy in the UK and internationally is primarily concerned with employment-related impacts, since policymakers expect the threat and imposition of benefit withdrawals to speed up returns to work. These employment effects are also implicitly assumed to bring about additional positive knock on effects, such as improvements in health.

A growing evidence base, however, contests these assumptions. Existing qualitative research, for example, demonstrates the acute psychological impact of sanctions on claimants. Similarly, my own study contributes to the limited quantitative evidence in this area, using large-scale longitudinal data, and finds that sanctions lead to increases in self-reported anxiety and depression.

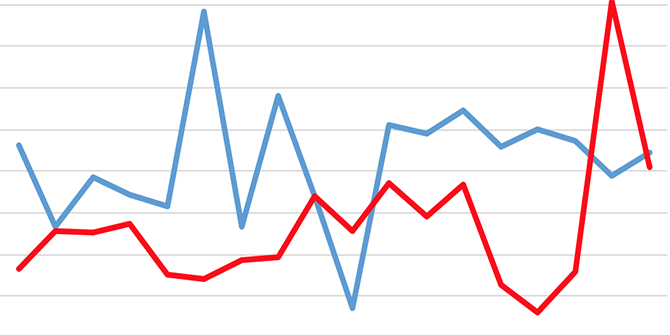

Individual-level sanctions data are currently not made available for use in academic research, and so the analysis is conducted at the local authority-level. Changes in Jobseekers Allowance sanctions policy during the Coalition Government (2010-15) are the specific focus and robust methods are used to take into account the influence of additional factors. This enables the analysis to more accurately estimate the specific effect of higher rates and longer durations of sanctions on mental health outcomes.

Importantly, the study provides clear evidence that increases in rates of sanctions within local authorities are associated with increases in the number of people suffering with anxiety and/or depression. This is clearest following the Welfare Reform Act 2012, which dramatically increased the average length of sanctions. In the post-reform period, every ten additional sanctions applied per 100,000 working-age population per quarter are associated with approximately eight additional people reporting that they suffer from anxiety and/or depression.

The need for reform

There have been several official investigations into sanctions policy since the 2012 reforms were implemented. The most recent of these concludes that the reforms were not informed by an appropriate evidence base and that their effectiveness needs to be urgently evaluated. This was reiterated by the UN’s Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights in his assessment of the UK conditionality and sanctions regime.

Whilst additional research at the individual-level is warranted, the findings detailed in my research are consistent with existing evidence. Current research indicates that the increased severity of sanctions had no observable impact on flows into employment but have led to increases in both food bank usage and antidepressant prescribing.

Sanctions policy within Universal Credit is based on a similar regime of conditions, sanctions ,and associated hardship payments. Enduring changes to sanctions policy are therefore needed as the UK leaves lockdown. First, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) should broaden the concerns of sanctions policy, beyond the narrow focus on employment, and assess the impacts of sanctions on health and well-being. Mental health and labour market outcomes are likely to be interrelated; the adverse mental health impacts of sanctions could plausibly affect people’s ability to search for and attain paid work.

Second, there is a need to reduce the length of sanctions and/or the proportion of benefit that is withdrawn. Positively, the DWP has recently ended sanctions that last for 156 weeks, admitting that they are ‘counter-productive’. Nevertheless, sanctions are consecutive within Universal Credit, which means that some will be affected by penalties that last longer than the new apparent maximum of 26 weeks.

Third, the hardship payments system is insufficient and also needs to be reformed. The adverse mental health impacts detailed in my study are observed even though the rate of hardship payments increased in the post-reform period. Hardship payments within Universal Credit are awarded for a restricted set of reasons and are repayable, leading to even fewer claimants receiving them than in the past.

Finally, the application of sanctions should be limited to a last resort. Initially, Universal Credit operated with a very high rate of sanctions, though this has since been reduced. The low rate could be maintained by implementing a warning system; limiting the number of reasons for which sanctions apply; and establishing clear rules for what constitutes a ‘good reason’ for non-compliance.

According to a recent assessment, current sanctions policy can be considered to be ‘cruel, inhuman and degrading’. Importantly, there are straightforward steps that can be implemented to minimise the harms associated with sanctions and to help realise the basic right to a social minimum.

___________________________

Note: the above draws on the author’s published work in Social Policy & Administration.

Evan Williams is a Research Associate at the University of Glasgow.

Evan Williams is a Research Associate at the University of Glasgow.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: by Ben Garratt on Unsplash.

2 Comments