Across the country, there are still massive inequalities in life expectancy and health outcomes. Indeed a national ‘health lottery’ is still very much in existence. David Taylor-Robinson examines the recent drastic cuts to local authority budgets and finds that the most deprived areas will be cut the most, and this will exacerbate existing inequalities in health and welfare.

Across the country, there are still massive inequalities in life expectancy and health outcomes. Indeed a national ‘health lottery’ is still very much in existence. David Taylor-Robinson examines the recent drastic cuts to local authority budgets and finds that the most deprived areas will be cut the most, and this will exacerbate existing inequalities in health and welfare.

Local government received what some consider the harshest settlement after last year’s Comprehensive Spending Review, with an average cut of 7.1 percent to local authority budgets. It has become clear that the budget cuts imposed upon local authorities are much greater in more deprived areas, and while much of the recent debate has centered on the effects on specific services such as libraries, these cuts are also very likely to have adverse consequences to people’s health in these areas. This is at odds with the coalition government’s stated intention to reduce health inequalities.

“Fair Society, Healthy Lives” is the title of the current review of health inequalities by Sir Michael Marmot. This highlights the fact that health inequality is a barometer for social inequality, and more broadly an indicator of social justice. In the current debate about what fairness means, one can argue that fairer societies will have more equal health outcomes, such as life expectancy.

In the UK there are still large differences in life expectancy at birth. For instance in 2008 there was a 13.3 year gap in male life expectancy comparing Glasgow (71.1 years) to Kensington and Chelsea (84.4 years). Social policy interventions are necessary to address this “natural lottery” of birth.

The variations that exist in life chances in the UK – as measured by life expectancy, health outcomes, and quality of life – are strongly correlated with measures of socioeconomic status. Reducing these inequalities in health has been identified as a key policy issue at local, national and international levels. However, in England, we are failing to reduce the relative gap in infant mortality and life expectancy, and to achieve the inequalities targets that set out to reduce these gaps by 10% (ref “Fair society, Healthy Lives” as above). “Fair Society, Healthy Lives” sets out a “social determinants” approach to addressing health inequalities, that recognizes that these differences are a result of the conditions in which we are born, grow-up, work and age. The recent coalition government’s public health white paper concurs with this view of health inequalities:

We still live in a country where the wealthy can expect to live longer than the poor.

We know that a wide range of factors affect people’s health throughout their life and drive inequalities such as early years care, housing and social isolation.

Furthermore, it states:

Local government is best placed to influence many of the wider factors that affect health and wellbeing. We need to tap into this potential by significantly empowering local government to do more through real freedoms, dedicated resources and clear responsibilities, building on its existing important role in public health.

Amidst the current turmoil of the planned changes to the NHS in England, there are plans to create a new public health service, based in local authorities, with a ring fenced budget weighted for inequalities. However, one must consider this against the backdrop of widespread cuts to local authority budgets across the country.

The social determinants of health – the things that really influence life expectancy – include education, housing, employment, transport and the quality of the built environment. All of these are directly influenced by local authority spending on things such as children’s services, adult social care, and planning and regeneration. A recent report on the role of local authorities in addressing health inequalities outlines the mechanisms by which local authorities can make a difference as an employer; through the services they commission and deliver; through regulation; and through community leadership. The local authority budget cuts represent an all out assault on these social determinants of health.

“Giving every child the best start in life” was the main recommendation of “Fair Society, Health Lives”, and the Sure Start programme was identified as one of the key delivery mechanisms for achieving this goal. Sure Start was established as a flagship early child development intervention to promote child health and to attempt to break cycles of intergenerational health inequality. As a consequence of the budget cuts, Sure Start centers in some of the most deprived areas are currently under threat of closure. This is likely to have a direct, and detrimental effect on health inequalities in the future.

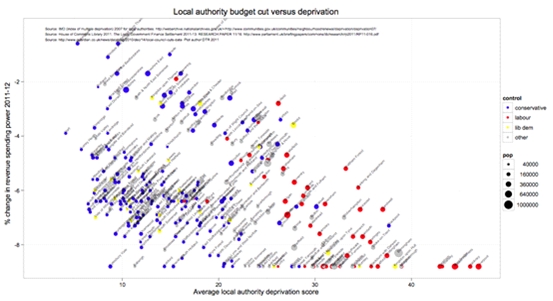

What we can see from the graph below is that the largest budget cuts are in the most deprived areas, and that the cuts appear to be larger in Labour controlled local authorities (analysis in table). For example, in London, Hackney and Tower Hamlets Councils will be seeing cuts of 8.9 per cent, while Richmond and Windsor are only cut one percent or less.

The graph uses publicly accessible data to illustrate the percentage change in Local Authority revenue spending power in 2011-12 (budget cut) by average local authority Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score, and political control. The IMD score is a measure of socioeconomic status, used widely by the ONS and in government statistics in England. The IMD combines a number of indicators measured at the census, covering income, housing, employment, crime levels, health and education, into a single deprivation score for small areas in England.

Table 1: Analysis of budget cut data

| Estimate (%) | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-value | |

| Change in allocation per unit increase deprivation score | -0.09 | -0.11 | -0.07 | 0.000 |

| Average change for conservative areas | -5.84 | -6.13 | -5.55 | 0.000 |

| Added change in Labour LAs | -1.20 | -1.81 | -0.60 | 0.000 |

| Added change in Lib Dem LAs | -0.27 | -1.07 | 0.54 | 0.511 |

| Average cut for North of England | -6.80 | -7.10 | -6.49 | 0.000 |

| Difference between North and South | 1.14 | 0.73 | 1.55 | 0.000 |

These findings are corroborated by the Government’s own research, which states:

There are larger falls in revenue spending power for the more deprived authorities as they are more reliant on this central government money than the less deprived who raise a higher proportion through the council tax.

These cuts are further exacerbated by the government’s policies towards Councils. While they trumpet ‘localism‘ and giving local authorities more freedom, there has been a country-wide council tax freeze this year, and councils face little or no ability to increase their own revenue streams even when faced with a much reduced grant from central government.

Cutting spending on the social determinants of health in this manner is at odds with the government’s stated intention to address health inequalities outlined in the public health white paper, and is in fact likely to widen health inequalities. Furthermore, it questions the Chancellor’s assertion that “we are all in this together”.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Fantastic article and graph, well done. My understanding is that some Local Authority budgets are cut more than others because where they had previously been funded based on need, and more relatively deprived areas’ needs are obviously greater and so they received relatively more money than relatively advantaged areas. Have I understood the situation correctly?

Davy – you’re spot on!

Excellent article Dave….hope these facts influence the conscience of decision makers. Interestingly the knowledge on social determinants has been in the public domain in the UK since at least 1982 via the Black Report. Unfortunately there has been little emphasis on these systemic factors, and instead a misguided over-emphasis on individual responsibility.

It’ll be interesting to come back to this chart in ten years and see how the figures match up against changes in public health outcomes across Local Authorities.

Thanks Jim – the link is live now.

Fascinating article, but the link to the larger version of the chart is broken.