Jonathan Wheatley draws on recent data following the European Parliament election to strengthen the view that the so-called Brexit divide is not only about the EU, but it is instead about a range of issues relating to identity. He considers what the implications of these findings are for party strategists.

Jonathan Wheatley draws on recent data following the European Parliament election to strengthen the view that the so-called Brexit divide is not only about the EU, but it is instead about a range of issues relating to identity. He considers what the implications of these findings are for party strategists.

The May 23 elections to the European Parliament (EP) were unexpected and, for Brexiteers, undesired, given that the UK was supposed to have left the EU on 29 March 2019. Nevertheless, they occurred at a time of political turmoil and provoked more interest than one would expect. Turnout increased by 1.5% to 36.9%, the highest turnout in EP elections since 2004 and the second highest turnout ever. Unsurprisingly, the election was dominated by a single issue: Brexit. Leavers deserted the Tories in droves, favouring instead Nigel Farage’s new Brexit Party, while Labour remainers also left their party in favour of the Liberal Democrats and Greens. The SNP dominated in Scotland, while Plaid Cymru took second spot in Wales (behind the Brexit Party).

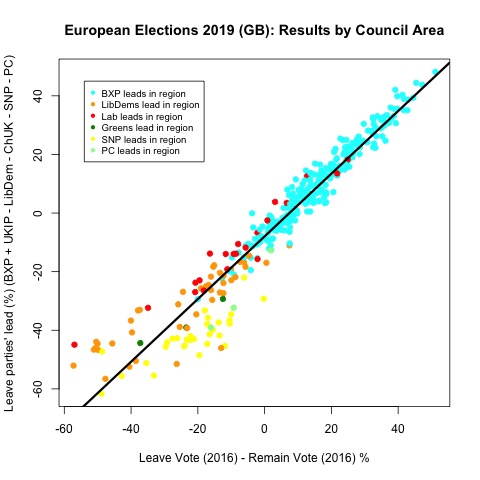

Votes in these elections were counted by local authority area, rather than parliamentary constituency, enabling a direct comparison between the 2019 election results and the 2016 EU referendum results in all counting areas. The diagram below compares the difference in 2019 between the combined vote of the so-called ‘hard Brexit’ parties (The Brexit Party and UKIP) and the combined vote of the parties that want to stop Brexit (Liberal Democrats, Greens, SNP, Change UK and Plaid Cymru) with the difference in 2016 between the Leave vote and the Remain vote. The dots on the map represent each counting area and are coloured to represent the party that gained the highest number of votes in the EP elections in the area.

The map shows that, on average, hard Brexit parties garnered more votes than anti-Brexit parties in regions where the Leave vote had been more than 54%, but anti-Brexit parties had the advantage where the Leave vote had been lower. More importantly, the divergence between regions in 2019 was greater than it was in 2016. At one extreme, we see that in Boston (Lincolnshire), where 75.56% voted to leave in 2016, 63.6% voted for the Brexit Party or UKIP, while just 15.3% voted for anti-Brexit parties. At the other extreme in Cambridge, where 26.1% voted to leave in 2016, anti-Brexit parties (LibDems, Greens and ChangeUK) enjoyed a massive 56.6% lead over their hard Brexiteer rivals.

This geographical divide seems be reflected in a deep ideological divide that cuts through society. According to a British Social Attitudes survey carried out in mid-2018, 40% of voters claimed to be either a ‘very strong Remainer’ or a ‘very strong Leaver’, while just 8% said they were are a ‘very strong’ supporter of a political party.

My own research confirms this divide. It draws from data generated by 43,404 users of the WhoGetsMyVoteUK Voting Advice Application, developed at Oxford Brookes University and deployed in Great Britain in the run-up to May’s EP elections. Users of the application were asked to express their opinions on 28 policy statements on a range of issues including the EU, the environment, privatisation/nationalisation, public spending and immigration. Their answers were then matched with the party or parties that best corresponded with those views. The analysis looks at the underlying ideological dimensions that inform these responses and throws up some interesting insights.

Mokken Scale Analysis was used to search for latent dimensions that underpinned users’ responses to the policy statements and identified two distinct dimensions. The first is a traditional economic dimension of left versus right that draws on issues such as redistribution of wealth, zero-hours contracts, and the privatisation/nationalisation of public services and utilities. The second is a cultural dimension that unites quite a large number of issues for which users’ responses are very closely correlated with one another – more closely, in fact, than the economic items. These issues included four on the UK’s relationship with the EU (the benefits of EU integration in general, whether to revoke Article 50, whether to leave without a deal and whether to have a second referendum); the others were on the cultural benefits of immigration, whether global warming has been exaggerated, whether to legislate for gender equality, the death penalty, the role of Islam, whether to allow those who fought in Syria to return to the UK, rights for same-sex couples, LGBT-inclusive education and foreign aid.

The close correlation between responses to these items suggests that the so-called Brexit divide is not only about the EU but is instead about a range of issues relating to identity and how to cope with a changing world within and beyond national borders. It distinguishes ‘cosmopolitans’, who embrace transnationalism, immigration, environmentalism and multiculturalism, from more traditionalist Eurosceptic ‘patriots’, who look to the community and the nation for support and are suspicious of multiculturalism and cultural change more generally. It reflects the divide proposed by David Goodhart between footloose ‘Anywheres’ and rooted ‘Somewheres’.

Respondents to WhoGetsMyVoteUK were far more polarised on these cultural issues than on economic issues of left versus right. The two diagrams below show the distribution of respondents along both dimensions. The single-humped curve on the left suggest there is a degree of consensus around economic matters, while the double-humped curve on the right indicates sharp polarisation on matters of culture and identity.

So what does this mean in terms of party strategy? In a nutshell, this analysis suggests that if any party or electoral coalition gains a monopoly of votes on one side of the culture/identity divide, then that party will win, probably with a majority, providing voters on the other side of the divide are split between two or more parties. This is a consequence of the UK’s first-past-the-post voting system.

Of the seven parties from Great Britain that won seats in the European Parliament, five tend to attract more cosmopolitan Remainers: Labour, the LibDems, the Greens, the SNP and Plaid Cymru. This poses a major problem, as the Remain vote risks being split between these parties. While the SNP is likely to bag most votes (and seats) in Scotland, divisions amongst Remainers may prove obdurate in England and Wales. Labour’s policy of ‘constructive ambiguity’, of appealing both to cosmopolitan Remainers and to more patriotic Leave voters in the Labour heartlands, proved rather successful in 2017 but is unlikely to work today as there are fewer votes available in the middle (see the right hand diagram above). If Labour fails to appeal to Remain supporters, the Liberal Democrats have the best chance of capturing that vote. However, to do so they would probably need to enter into an electoral pact with a resurgent Green party and perhaps even Remainer Labour MPs that cannot support Jeremy Corbyn’s prevarication over Brexit.

At the same time, for the Conservative Party to win it will need to capture the Leave vote by advocating as hard a Brexit as possible, perhaps forging an electoral pact with the Brexit Party to prevent Leave voters from decamping to Nigel Farage’s outfit. The risk of this strategy is that any electoral gain it brings could be short-lived. If the threat of a hard Brexit is actually carried out, the economic fallout of such a course of action may make voters reconsider. The incentives for the Tories to hold a snap general election before Brexit are therefore rather strong.

______________

Jonathan Wheatley is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Oxford Brookes University. His latest book is “The Changing Shape of Politics: Rethinking Left and Right in a New Britain” (Palgrave, 2019).

Jonathan Wheatley is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Oxford Brookes University. His latest book is “The Changing Shape of Politics: Rethinking Left and Right in a New Britain” (Palgrave, 2019).

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Really interesting, especially the fact that there is consensus on economic issues and this is not reflected in the policy offerings of the parties, which are diverse on a spectrum between the status quo and attempts at ameliorating the downsides of globalisation and the financial crisis.

So there is a apradox in that the division on cultural issues means that people are unlikely to vote for that economic consensus though it would be a road to unity

Voting your cultural conscience runs the risk of getting stuck in a permanent loop that magnifies the cultural differences because the negative effects of allowing one version of economic policy to be implemented (especially maintaining the status quo) as a side effect of the cultural vote will be felt more by one group than another.

Divisions will increase as cultural issues are more significant to those who have their basic needs covered and these are going to be a diminishing group.

The underlying premise is flawed.

The 2016 referendum and the 2019 EU elections are not directly comparable because they had a different electorate.

If I have a population of 100 and 80 can vote in a GE and the referendum, and 100 can vote in the EU elections, then I cannot compare the 40 that vote in the latter with 40 that vote in the former, when up to 20 of those voting in the latter are virtually guaranteed to be remain supporters by virtue of the fact that they are EU originated residents unable to vote in a GE or the referendum.

So this is why the premise is flawed and the two results (and a GE) are not comparable.

I began reading the article however I had read quite a bit & still hadn’t reached any material that anyone , with even a passing interest in these things , would not already be aware of. To not state clearly & early that up to 3 million voters were denied a vote , in my view is very revealing , so I didn’t continue to read the article.

Kind regards