Theresa May has rejected calls for the UK parliament to have a vote on the terms of Brexit, however on 12 October she accepted that there will be an opportunity for parliament to debate the country’s strategy before Article 50 is triggered. Valentino Larcinese states that the argument against parliament having a strong role in the process rests on a decidedly misguided notion of the ‘will of the people’.

Theresa May has rejected calls for the UK parliament to have a vote on the terms of Brexit, however on 12 October she accepted that there will be an opportunity for parliament to debate the country’s strategy before Article 50 is triggered. Valentino Larcinese states that the argument against parliament having a strong role in the process rests on a decidedly misguided notion of the ‘will of the people’.

According to Britain’s Prime Minister, Theresa May, giving the UK’s Parliament a vote on Brexit plans will “thwart the will of the British people”. As political science and political economy students usually learn during week 1 or 2 of their courses, this statement makes no sense. A well-established literature in social choice theory, of which Kenneth Arrow’s impossibility theorem is probably the most important result, shows that unfortunately the “will of the people”, British or otherwise, does not exist.

Brexit and the ‘will of the people’

It is difficult enough even to define and understand the desires of single individuals, as shown very clearly by recent advances in behavioural economics. But let’s ignore this complication and let’s assume that everybody in a polity (say the UK) has well defined preferences, is well informed and it is a fully rational person. Let’s even concede that these preferences remain stable over time.

These assumptions, unrealistic as they are, are nevertheless insufficient to result in collective rational preferences. In other terms it is impossible to aggregate individual preferences into a rational “will of the people” if we want to give a fair representation to all views and opinions in society (i.e. no dictatorships) and we also think that people should be entitled to have any views they want. The debate on Brexit (or any other matter) would then be a better debate if it could avoid metaphysical representations that portray multiple individuals as a single entity.

William Riker, one of the most prominent 20th century political scientists and one of the founders of the rational choice approach to politics, famously used Arrow’s results to distinguish between a populist and a liberal view of democracy. In the populist view, democracy tries to aggregate the desires of individual members of a society into a collective will (like Theresa May would claim has happened with the Brexit referendum). In the liberal view the purpose of democracy is rather to keep elected representatives held to account.

These representatives do not deliver the public will (which does not exist), but must respond to the public for their choices according to some pre-defined procedures. We do not necessarily have to agree with Ricker, but still the problem remains of how to take collective decisions and how to interpret these decisions once they are taken. After all, democratic regimes also allow referendums, whereby decisions on some matters are directly taken by the voters: referendums might not deliver the people’s will but, once we agree that this is a good procedure, then the outcome should be respected.

May’s theorem

There is one insight in social choice theory which could support Theresa May’s approach to Brexit. This is called May’s theorem and is named not after the current Prime Minister, but rather after the American mathematician Kenneth May who proved the theorem in 1952. It is also useful to clarify that the other famous theorem “I am the Prime Minister therefore I am right” has nothing to do with it.

The theorem suggests that, in binary choices (i.e. when we have only two alternatives), majority voting is the best system and the only one which satisfies a number of desirable properties. On 23 June the choice was binary (Leave or Remain) and therefore the outcome of that referendum, which has been reached using the best possible rule, gets us as close as possible to the metaphysical idea of the “will of the people”.

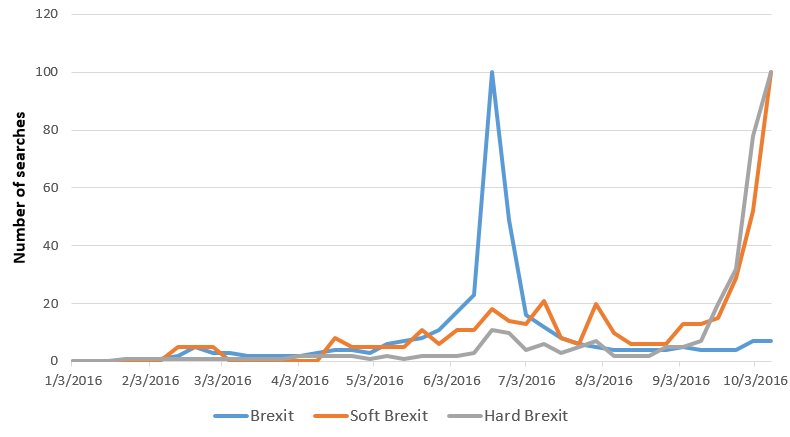

But while May’s theorem could be used as the foundation for Theresa May’s “will of the people”, we have now learned that there are at least two versions of Brexit, hard and soft, which only came to the forefront of public debate after the referendum, as shown by the graph below reporting the weekly frequencies of Google searches on “Brexit”, “Soft Brexit” and “Hard Brexit” in the UK. The blue (“Brexit”) spike refers to the referendum week. It is only in September that a clear awareness seems to have emerged of the existence of at least two possible Brexit options.

Figure: Weekly number of searches for “Brexit”, “Soft Brexit” and “Hard Brexit” on Google

Source: Google Trends

Had the Remain camp won the contest we would have probably learned that there was more than one Remain option too. So what has happened is that a complex multidimensional choice has been reduced by the referendum to only two options: the consequence is that a choice has been made but it’s not clear which one. Note that if this was not the case, any discussion of hard or soft Brexit would be superfluous: the referendum outcome would provide by itself an indication of what should be done now. Good bye May, we are back in Arrow’s world!

The importance of institutions

One of the key insights in Arrow’s theorem is that institutions matter: when three options or more are available, different procedures can induce the same society (with exactly the same individuals) to take different decisions on the same matter. We might, for example, end up with a different government depending on whether we use a first past the post or a proportional electoral system. We need to acknowledge this unpleasant characteristic of collective decision-making: there is nothing divine about these rules and about the decisions which are taken using them. The best we can hope for is that everybody (or at least a qualified majority of citizens) agrees on the rules themselves irrespective of the outcome that they deliver.

This is the reason why most constitutions provide a bias in favour of the status quo when it comes to issues of extreme importance, like amending the constitution itself. While ordinary policy is normally taken by simple majority rule, constitutional changes require more complex procedures. These procedures typically create a status quo bias both to protect minorities against a “tyranny of the majority” and to make it more likely that the changes have been carefully evaluated, possibly by different independent players. Broad coalitions must then be formed to pass a constitutional change.

Amendments to the US constitution, for example, must be voted by two thirds of both the House and the Senate and must then be approved by three quarters of the 50 state legislatures. In Italy there will soon be a referendum on a major constitutional reform. This reform has already been passed twice by the parliament (with a “reflection pause” of at least three months between each vote).

In comparison, it is quite extraordinary to observe the levity of the Brexit decision-making process, ever since Cameron committed to a referendum. Brexit is no less important that a major constitutional change (except maybe that it is more costly) and yet, following a consultative referendum, it now seems to be taken as an accomplished, inevitable outcome, which only needs to be implemented (if only we knew how). Brexit is “the will of the British people”, the contemporary correspondent of the divine will in the ancient regime.

Such misunderstandings as to the interpretation of the outcome of the referendum can emerge for many reasons, including short-term political opportunism, but there are at least two other reasons worth discussing. The first is the somewhat naïve view that democracy is the simple implementation of majority rule and that the referendum has enabled us to discover the “will of the British people”. Unfortunately, the absence of written constitutional rules has allowed this simplistic view to become prevalent.

The second reason stems from the gravy train which Brexit is creating in Whitehall. There are few things which are more desirable for politicians than being able to expand their influence by distributing jobs and perks. So far two new departments have already been created specifically to deal with Brexit and they have hired (or poached from other departments) hundreds of civil servants. It is now anticipated that the Brexit ministry will need to double its size and one wonders how many times it will have doubled before Brexit is accomplished.

Outside of these departments, it is hard to think of any area of public administration that will remain unaffected by Brexit. The civil service will have to expand, hiring thousands of new employees who will spend their days reviewing EU laws and the ways they currently affect the British legal and regulatory system, preparing material for negotiations with the EU and for the individual new trade deals that will have to be struck with dozens of countries, delving into the intricacies of fisheries, agriculture, financial services and virtually every other sector of the British economy.

Armies of external consultants will be hired and paid thousands of pounds per unitary day of work. Nobody knows the impact of this process on the UK budget but, over the many years that the process will take, it could easily add up to billions of pounds. In brief, for politicians Brexit is a rare opportunity to expand and shape public administration. If a populist view of democracy seems to reflect the current prevalent mood in the British public, the gravy train might have its appeal for decision-makers.

It should be clear at this point that allowing parliament to vote on Brexit plans will not thwart the will of the British people. Yes, a referendum has taken place and, whatever its interpretation, there is no doubt that its outcome must be respected. At the same time, however, taxpayers’ money, people’s jobs and more generally the prosperity of this country also deserve respect.

This does not mean that the outcome of the referendum should be ignored – I would never claim this – but simply that the people of this country deserve adequate deliberation and decision-making procedures to determine what has to be done now. It would be paradoxical if the parliament was not part of this process since one of the most important arguments in favour of Brexit concerned precisely the sovereignty of Westminster against the technocracy of Brussels. Even more paradoxical is the fact that the government intends to interpret the outcome of the referendum as a mandate to do pretty much what they like.

____

Note: This article was first posted on EUROPP – European Politics and Policy.

Valentino Larcinese is Professor of Public Policy in the Department of Government at the London School of Economics.

Valentino Larcinese is Professor of Public Policy in the Department of Government at the London School of Economics.

You know one thing that i really didn’t like during the debates leading up to the vote last spring was that boris and nigel farage were so often personally attacked yet they never insulted others. I felt like “poor old boris people keep mocking him calling him names and farage too and yet they would sit there taking it all like on say the question time panel and people would be really insulting and personal about him and the poor bloke took it yet never did he mock them or be personal about others. It was cruel to be so mocking of boris and farage.

I really disliked that. It was like the elite were so supercilious and smart arsed insulting them personally and been really personal yet they just stood there and took it and they were not mocking those people back. it was like organised bullying and i really disn’t like that. They took it all and they didn’t insult them back.

I voted leave and couldn’t beleive how many of the elite ran down us brits like we were so unable to cope as a nation and we were so inept without the eu. We would be so lost witout the eu as if us brits are so gormless and we need them so bad. Runing down britain. I don’t see camps of people at dover wanting to get away do you?

Running down britain. It reminded me of de gaul in the 70’s saying ‘NON NON NON” Smugly about us brits after we protected him from the nazis during the war. Also I felt really angry that people in the media ran down the ordinary working men and women of britain like we were ignorant and thick when i think, who is it when the chips are down who go and fight for this country during the war? Who was it that went out as cannon fodder in the second world war if not the ordinary british tommy and when ordinary people up and down the land wish to have our hard faught for democracy we are derided as thick and ignorant. It was those ignorant men and women that went out in their millions and faught for our democracy against the nazi’s. I always think emotionally of the words “say of us that we gave up our today for your tomorrow” and now smart arsed elite mock us and deride us for wanting our own country to be a democracy. I am so glad that us ordinary simple folk stuck it to them all. They mocked the elderly for voting out as if the elderly should have no say……..one day you may be old too so dont be so creul and mocking of the elderly who went out the ordinary tommy to fight and die for us to have that basic freedom so your mocking them just makes you look so smug and out of touch. it is always the simple ordiary brits that they deride that are the ones who go out and fight for these smug lot when there is no other way.

Boris and farage took such personal attacks yet they never ran others down they sat there been insulted and never were they insulting or personal. Also, they say if we vote leave there is no going back that is it. I’m sorry why is it so set in stone??? We can make it whatever we want we put a man on the moon why is it so set in stone??? we are all here just passing time so why is it so final???? if we want to make changes later why cant we???? we built the whole world we can do whatever we think will work why do they keep saying it is so final and no going back??? it isn’t ordained by God is it??? we can change whatever we want if we want to. But I am so glad we left that old dinosaur of the eu. Just my thoughts

You say “I don’t see camps of people at dover wanting to get away do you?”

But actually, Britons are more likely to leave the UK than return: “British citizens are the only group characterised by continuous net-emigration since 1991 (i.e. negative net migration). In 2015 there were 39,000 more British citizens moving abroad than coming to live in the UK. This is a substantial drop from 2011 when it stood at 70,000. Net emigration of British nationals peaked in 2006 at 124,000.”

Source: http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/long-term-international-migration-flows-to-and-from-the-uk/

But I do agree with you: “Also, they say if we vote leave there is no going back that is it. I’m sorry why is it so set in stone???”

Standard project management practice would be to have a project review when there is a plan in place whose costs, benefits and risks can be assessed. So there should be a referendum on the terms of Brexit

Facebook: Campaign for the Real Referendum – on the Terms of Brexit

Having neatly demolished the idea of will of the people on Brexit you then say that “the outcome of the referendum should be respected”. This is repeated by almost all politicians interviewed – typically “I was a Remainer but I respect the outcome”. Why? If you believe, as many of us do, that Brexit is a huge mistake and a disaster for the country why not fight to reverse the decision? Those who were against capital punishment and gay rights fought against the so-called will of the people and won. It is time for Remainers to stop meekly respecting the referendum, get off their padded bottoms and fight to keep us a part of the greatest unifier of Europe since the Roman Empire – and this time it is voluntary.

The PM serves only so far as she enjoys the confidence of teh House of Commons. If it chooses to let her conduct the negotiations directly then that is a perfectly acceptable outcome under the constitutional arrangements currently obtaining. It is hard to see how any detailed parliametnary oversight could in fact

The referendum should be respected as far as it goes. That means that the government should plan and negotiate Brexit, work out the domestic policy consequentials, assess the impact – and stop there.

While I am sure that every Leave voter knew what they wanted, the absence of a Leave plan means that none knew what they were going to get. Both of the earlier comments on this post illustrate a fallacy. One that Brexit is a single decision with no options; the other that the individual’s view of what he was voting for is what every other Leaver was voting for. Moreover, it would be fallacious to assume that a bare majority for Brexit when every Leave voter could project their own Brexit onto the ballot paper will automatically turn into a majority for Theresa May’s Brexit.

So I agree with the original post that Parliament now needs to scrutinise the Government’s proposals – only Parliament can do that line by line. And Parliament should decide on the Brexit package.

But then what? Someone has to decide whether we Brexit on that package, or whether we Remain. Having gone down the referendum route, I do not think that Parliament has the political authority to reach that decision in a way which would satisfy June’s Leave voters if the decision falls out for Remain. So there should be a referendum on the terms of Brexit, once these have been agreed.

Facebook: Campaign for the Real Referendum – on the Terms of Brexit

Parliament is there to respect and obey the will of the people, we were given a free vote we voted to leave the eu, any attempt to ignore the will of the people would be unconstitutional, and anti democratic, after all more people voted to leave the eu than to elect the government.

You didn’t read it Barry, did you?

Contrary to the opinion of the author …

http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

Article 21.

(3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Key word there is “periodic”. Periodic elections always give you another choice within five years or sooner. Referendums don’t. That is why Clement Attlee stated that referendums are “a device of dictators and demagogues”.

The Brexit campaign was built on the ideas

1) Take back control in order that Britain become an independant sovereign nation which makes itsbown policy, laws and rules.

2) Control immigration and consequently have border controls and a policy of immigration management.

3) Not paying EU contributions

4) To have the ability to stike free trade agreements independent of the EU.

5) To leave the EU

Basically these stated aims amount to a hard Brexit and as such the electorate were informed of the choice available albeit binary.

EEA membership still means that 1-3 apply and all research has shown that the Brexit vote reflected a desire for 1 and 2 in particular. Therefore in terms of May’s theorem, a majority decision does reflect a hard Brexit and not a soft one.

Interesting arguments but firstly your argument can be repudiated by the fact that the Labour Party (or any other party) can include in its next election manifesto EU or EEA membership and therefore allow the people to decide through normal electorate processes. Secondly in order to overcome the dilemmas of the Condercet Winner, Arrow’s Impossibility theorem and May’s theorem is a question regarding the reformation of representative democracy and not a question regarding the EU referendum result which as shown above was a clear indication for a clean or hard Brexit.