The A-Levels fiasco is yet one more confirmation that the educational system remains elitist at its core, writes Diane Reay. She explains how the UK is still primarily educating the three social classes separately, for very different roles, and for different economic outcomes.

The A-Levels fiasco is yet one more confirmation that the educational system remains elitist at its core, writes Diane Reay. She explains how the UK is still primarily educating the three social classes separately, for very different roles, and for different economic outcomes.

Fifty years ago, my secondary head teacher summoned me to her study and bluntly told me ‘girls from your sort of background do not go to university’. She told me it would not be appropriate for a Free School Meals girl from a council estate to mix with what she termed ‘much more upper-class people’. Class inequalities have been hardwired into our educational system for decades.

But now it is the elite universities that are ring-fenced, not universities per se, with increasing numbers of working-class young people attending higher education. However, the majority are going to universities the middle and upper class do not want to go to.

The A-Level and GCSE debacle has been appalling, with a Conservative government attempting to level down grades for working-class students not once but twice. The now abandoned algorithm moderated down the grades predicted by teachers for 39% of A-Levels, predictions which The Sutton Trust had already warned were much more likely to be underestimated for working-class students than for their middle-class peers.

But, the grades scandal represents only the tip of the iceberg. Class inequalities, compounded by race and gender, permeate the whole system, not just one stage of it. We may now increasingly have working, middle, and upper-class universities but we have always had upper-, middle-, and working-class schools. Of even greater concern than the stranglehold wealthy pupils and private schools have on our elite universities is the class and race polarisation across all sectors and stages of British education.

Furthermore, despite the common assumption that, at least within the state sector, children are experiencing the same education, there are very apparent differences in the education delivered to working- and middle-class children. Even when they attend the same schools, the working classes are to be found in the bottom sets and streams where they experience a very different education to the middle-class children concentrated in the top sets. But largely as a result of a school choice system based on postcode, we now have working-class schools characterised by a narrow curriculum, teaching to the test, and an excessive focus on discipline. Recent research in the UK points to a disturbing social class difference in the pedagogy experienced by different social classes, with the working classes more likely to experience a pedagogy of poverty that pays little attention to critical thinking skills and adopts a “drill and kill” approach.

It is these working-class schools that will be hit the hardest in the latest funding round. Comparing per-pupil funding in 2020-21 to that in 2017-18, the Education Policy Institute found that Free School Meal pupils will have received increases of around two-thirds of the rate of non-Free School Meal pupils. Instead of reducing the social class gap in attainment, which OECD research shows widens for every year spent in education, our Conservative government’s new funding formula increases the money given to affluent schools at the expense of those in disadvantaged areas. This risks further increasing the social class inequality divide in education.

While there is constant talk about good and bad schools by parents and the media, there is rarely a recognition that good equates with upper- and middle-class intakes, while schools perceived to be bad are those primarily attended by the working classes. Instead, educational outcomes become the responsibility of teachers, ignoring a long history of research evidence which shows that education cannot compensate for economic and social inequalities in wider society.

The obsession with school improvement, the growing prominence of league tables, and the heavy hand of Ofsted have resulted in children’s attainment being attributed to the performance of school staff rather than the economic circumstances of children’s families. But such a conclusion flies in the face of research evidence which consistently shows only 20% of the variability in pupil achievement is attributable to school-level factors, while at least 80% is a consequence of family circumstances.

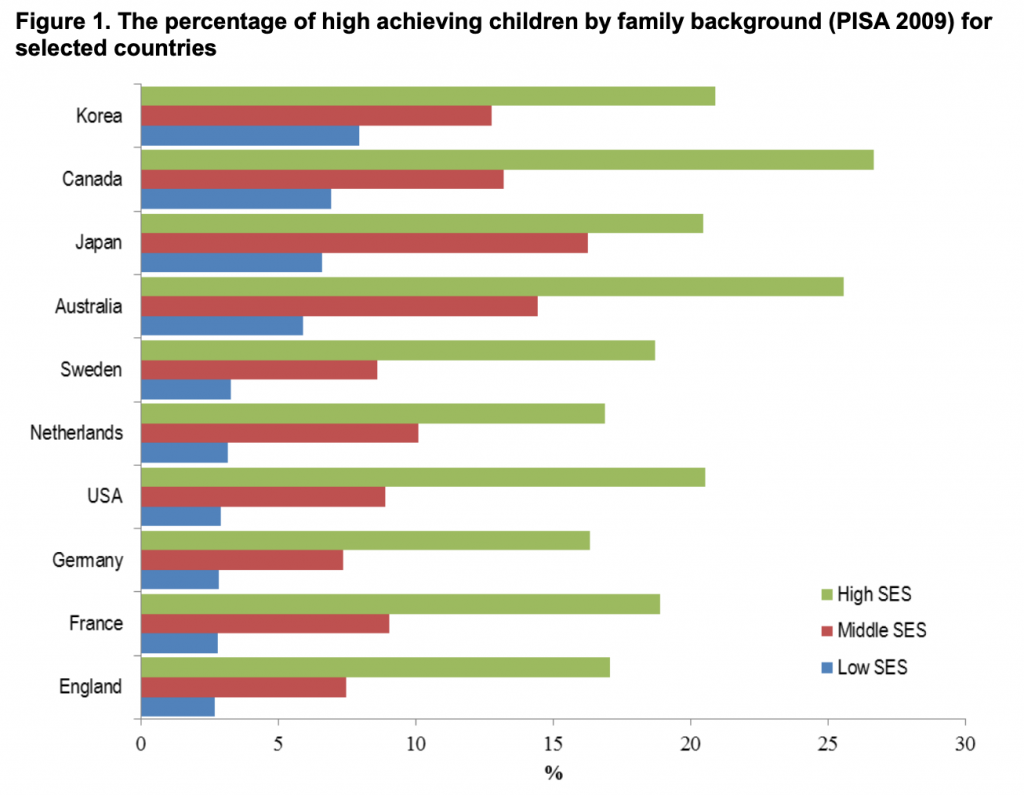

What we all too often overlook in the UK is the extent to which children’s educational prospects reflect the disadvantages and relative poverty of their families. Those who are poor, whose parents have low qualifications and no or low-status jobs, who live in inadequate housing and in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, are less likely to gain good qualifications themselves at school. And in the UK we are particularly bad at enabling poor children to succeed educationally when compared to other countries.

The original graph can be found here.

The original graph can be found here.

The chart shows that less than 3% of English children in the lowest SES group are educational high achievers, the lowest for all the countries surveyed. This suggests a disturbing gap between working-class children’s academic results and their educational potential.

And, despite the rhetoric around promoting social mobility and raising aspirations, the academy and free school movement has made things worse for working-class children, further increasing segregation and polarisation, and a growth in the unfair distribution of resources

The A-Levels fiasco is an amplification of a crude and unjust sorting process that positions the working classes as collateral damage in order to enable upper- and middle-class educational success. While it has uncovered how unfair our educational system is, digging further down exposes a system that remains elitist at its core. The educational system is still primarily educating the three social classes separately and for very different social roles and economic outcomes. As Brian Jackson and Dennis Marsden concluded in their seminal text Education and the Working Classes published in the 1960s, the British educational system is about selecting and rejecting in order to rear an elite. The current grades fiasco is yet one more confirmation that it still is.

___________________

Diane Reay is Visiting Professor of Sociology at the LSE and Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Cambridge. Miseducation, her book on social class inequalities in British education, was published by Policy Press in 2017.

Diane Reay is Visiting Professor of Sociology at the LSE and Emeritus Professor of Education at the University of Cambridge. Miseducation, her book on social class inequalities in British education, was published by Policy Press in 2017.

Dr Reay,

I thank you heartily for such a striking and candid assessment of the socio-economic stasis that goes on in our education system.

I want to ask you a question on behalf on my friend who is Head of Year 8 and teaches Maths at a state school in London. How would you advise them to support their students’ futures (most of whom are from low SES) without becoming wholly disheartened by the statistics which suggest an overall futility of their efforts?

I look forward to hearing from you Diane.

Warm wishes,

Harriet Freeman

Dear Harriet, thank you for contacting me. I have written a short paper for the NEU which I hope will be helpful for your friend. It’s called Research to reflect on: Addressing working class educational disadvantage

Helpful practice for valuing and including working class pupils in schooling

https://neu.org.uk/media/11646/view

all the best

Diane

Hi, how of the differences between countries do you think – if any – is down to cultural attitudes of kids and parents?